Media outlets are that the U.S. military is currently detaining an American citizen captured allegedly fighting on behalf of ISIS in Syria. The Trump administration has not released the citizen’s name or location, nor has it indicated whether the suspect will face criminal charges in federal court or be subjected to continued military detention.

But the right choice here is plain: It would be a grave error for the administration to resurrect the failed and illegal Bush-era policy of enemy combatant detentions. If, in fact, the U.S. citizen was fighting for ISIS, the surest way to safeguard both our Constitution and security is to transfer the suspect promptly to federal court to face criminal charges.

Even without knowing all the facts, the basic legal requirements for the suspect’s treatment, rights in detention, and prosecution are clear.

First, the United States may not subject any person in its custody to torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. Mistreating detainees is not only a war crime. It also undermines basic constitutional values and places U.S. troops in jeopardy by weakening respect for the law of war. This prohibition has long been enshrined in both the and U.S. law.

President Obama reiterated this prohibition in a 2009 by confining interrogation methods to those outlined in the U.S. Army Field Manual, and Congress codified it through the to the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act. The International Committee of the Red Cross, which monitors implementation of the Geneva Conventions, must be given access to all prisoners held in armed conflict within two weeks of their capture to ensure their treatment comports with international law.

Second, the detainee, as a U.S. citizen, is indisputably protected by the Constitution and entitled to the fundamental guarantees of habeas corpus and due process. In its landmark 2004 decision in , the Supreme Court ruled that U.S. citizens allegedly captured on a battlefield while fighting for enemy forces must, at a minimum, have a fair opportunity to challenge the allegations against them before an impartial decision maker. In 2008, the Supreme Court this basic guarantee to noncitizens held at Guantánamo.

Third, prosecution in federal court, rather than military detention, is the only legitimate course of action as a matter of domestic law and policy. The United States does not have the legal authority under its own laws to hold alleged ISIS fighters in military detention. The government may assert that empowers it to detain the suspect, but the AUMF at most authorizes the military to capture and detain suspected terrorists who were part of or who substantially supported al-Qaida, the Taliban, or associated forces engaged in hostilities against U.S. or allied forces.

This authorization, passed days after and in direct response to the 9/11 attacks, cannot be stretched to cover individuals fighting for ISIS, a group that did not exist at the time and that has publicly opposed al-Qaida. And indeed, the Supreme Court has to date only upheld the military’s power to detain individuals under the AUMF if captured while fighting on a battlefield in Afghanistan.

The prosecution of terrorism suspects by federal courts isn’t just the legal way to go — it has proven vastly superior to any military solution. Federal courts more than 620 individuals on terrorism-related charges since 9/11. While federal terrorism prosecutions have unfairly restricted fair trial rights in individual cases, they are still part of a legitimate system with time-tested constitutional safeguards and procedures.

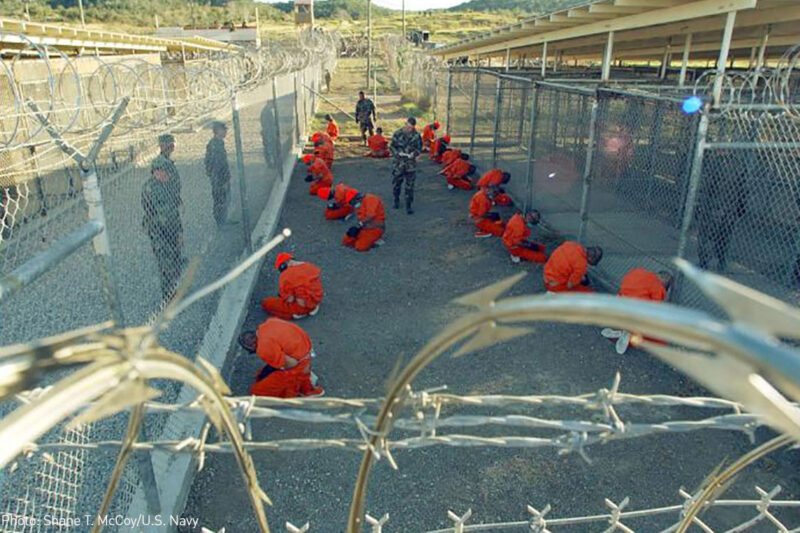

By contrast, the military commissions at Guantánamo remain stymied by legal controversy that stems from their underlying illegitimacy. The commissions eight individuals; four of those have been overturned on appeal in whole or in part. The military commission death penalty prosecution against Khaled Sheikh Mohammed and his alleged co-conspirators is mired in pretrial proceedings — raising fundamental fairness issues — with no trial date in sight.

Indefinite military detention without charge has proven equally problematic and lawless. The detention of alleged “enemy combatants” at Guantanamo violated human rights guarantees, resulted in widespread international condemnation, and created a category of “forever” prisoners that is an affront to basic constitutional and international law norms.

Under the Bush administration, nearly all “enemy combatants” were noncitizens, though the government occasionally extended the designation to captured American citizens, too. Perhaps most notably, the United States detained Jose Padilla as an enemy combatant following his arrest in May 2002 at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport. Confronted with the prospect of Supreme Court review, the Bush administration eventually transferred Padilla to civilian custody in January 2006 to face federal criminal charges. Padilla’s prolonged military detention and torture in military custody remains an enduring symbol of the abuse of executive power in the post-9/11 era.

Ultimately, even the Bush administration recognized the failure of so-called enemy combatant detentions and halted the practice for newly captured suspects. The Obama administration transferred all terrorism suspects, including those seized outside the United States, to federal court for criminal prosecution. But its delay in doing so after capture in some cases raised significant legal concerns. In , the military held a suspect, Ahmed Adulkadir Warsame, on a U.S. naval ship for more than two months before bringing him to New York to face federal charges. Through these delayed transfers, the U.S. government could use the cover of military detention to engage in coercive interrogations of criminal suspects without counsel or access to a court, in violation of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. We don’t know if that’s what’s happening in this case.

Both the Constitution and our government’s track record when it comes to detention make it clear: Suspected terrorists captured abroad should be transferred promptly to the United States for criminal prosecution. That goes for alleged ISIS suspects, too.