The ACLU’s Response to 9/11: An Insider’s Account

I woke up early on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, to fly from New York to Washington, D.C. I had been the ACLU’s national legal director for eight years at that point and was scheduled to give a breakfast talk at the annual meeting of what was then called the President’s Council, a group of ACLU donors and supporters. The other members of the ACLU’s senior leadership team were also present at the meeting, including Anthony Romero, who had begun his tenure as the ACLU’s executive director only one week earlier. Coincidentally, it was the same day that began as director of the FBI, a coincidence of timing that was later noted by both men.

I had originally planned to fly to Washington the night before, but my flight was cancelled due to severe thunderstorms. The weather changed dramatically overnight. The skies were blue and cloudless as the sun rose on 9/11 — “severe clear” in the parlance of airline pilots. My flight left LaGuardia Airport at 6:30 a.m. and arrived in Washington less than an hour later. It was a trip I had taken many times before. I can’t now recall whether I spent my time napping, reading the paper, or preparing for my talk — probably some combination of all three. I do remember that the flight was uneventful. There was no sense of what was coming, or how that day would transform our lives, our country, or the ACLU.

Steve Shapiro on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001

ACLU

By 8:30 that morning, I was standing at a podium in a windowless hotel meeting room. I had just begun my talk on the ACLU’s legal priorities and the upcoming Supreme Court term when I noticed an ACLU staff member whispering something in Anthony’s ear. Anthony then left his seat, joined me at the front of the room, and announced that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. None of us had cellphones at that time, and I don’t think we yet knew that a second tower had been hit by another plane. I am certain that we did not know whether what had occurred was an accident or a terrorist attack.

In search of a television, we all moved to the hotel bar where we watched the story unfold with the rest of the world. After a third plane hit the Pentagon, the hotel went into lockdown. No one was allowed in, and we could not leave. Our first priority was to establish that everyone who worked at the ACLU headquarters in New York was safe.

Participants at a meeting of ACLU supporters join other hotel patrons to watch TV on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001.

ACLU

It is one of my enduring memories of that day.

By mid-morning, the ACLU’s senior staff had gathered to draft a press statement. It was clear then that the U.S. had been subject to a terrorist attack, and the ACLU had already begun to receive numerous press calls asking us to comment on whether we were concerned that the government’s response to the terrorist attacks might imperil civil liberties. With the buildings still smoldering and so many people still missing, we decided to issue a press release expressing our sympathy for the families of those who had died and not to engage in predictions about what the government might do in the future at a moment of national mourning and overwhelming chaos. At the same time, we made it clear that we would be closely monitoring the government’s reaction and would defend the nation’s values and principles against any threats to civil liberties, if and when they arose.

We did not have to wait long.

A New Normal

Almost immediately, the government began to round up of Muslims on what were often technical immigration violations and to detain them under harsh conditions without access to family or lawyers. The first post-9/11 lawsuit filed by the ACLU in early December was an effort to force the government to disclose how many people had been arrested in this dragnet sweep, who they were, and where they were being held.

The government never claimed that secret imprisonments were consistent with legal norms that applied prior to 9/11. Instead, it that those legal norms had to be adjusted in a post-9/11 world in which “everything had changed.” It was a precursor of things to come.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

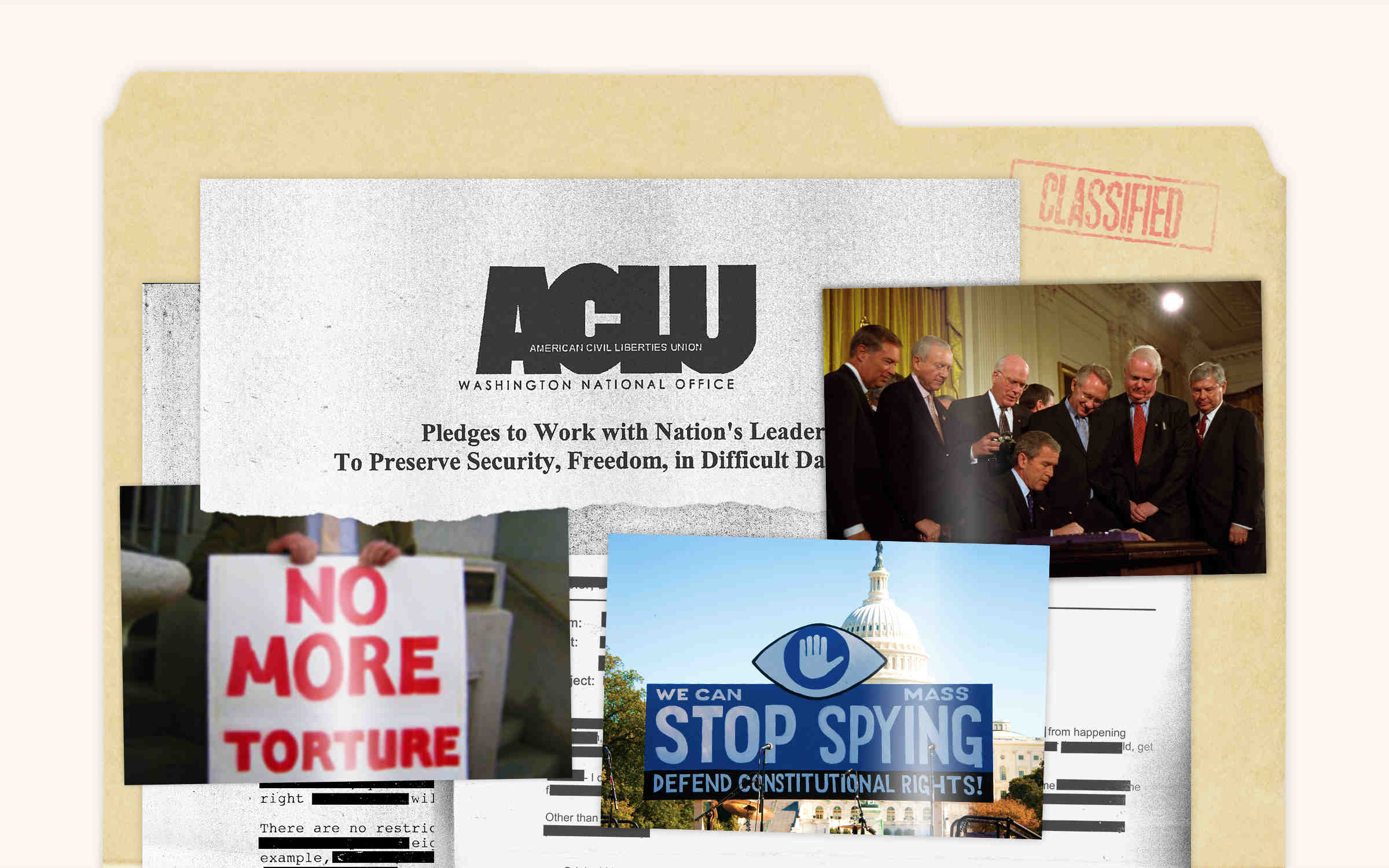

On the legislative side, Congress passed the U.S.A. on Oct. 26, giving the federal government vast new investigative powers that it claimed were necessary in the fight against terrorism. The ACLU opposed the Patriot Act at a time when very few others were willing to do so. Among other things, we objected to provisions that gave the government broad access to financial and other records without any need to show evidence of a crime or obtain a court order, expanded the government’s authority to conduct secret “sneak and peek” searches, and minimized judicial supervision of telephone and internet surveillance.

We also argued, more broadly, that our national security is undermined, not enhanced, when the nation sacrifices its commitment to civil liberties. And we pointed out that similar trade-offs in the past had come to be seen as sources of national shame and regret — from the of anti-war protestors in World War I to the of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Congress chose to ignore these lessons of history, and the Patriot Act passed with overwhelming majorities. It was not until many years later that we learned the full scope of government abuses unleashed by the Patriot Act.

President George W. Bush signs the USA PATRIOT Act into law in the East Room of the White House, Oct. 26, 2001.

National Archives

Our national security is undermined, not enhanced, when the nation sacrifices its commitment to civil liberties.

The ACLU never wavered from its role as a defender of civil liberties after 9/11, but the ongoing battle has never been easy. For many Americans, the threat of another terrorist attack in those early days was more real and palpable than the threat to civil liberties, especially if the civil liberties at risk belonged to some other person or group. Politicians were afraid to appear soft on terrorism. And, at least initially, the courts were deferential to the national security judgment of executive branch officials.

For years, every government brief in a 9/11-related case began with the same opening line, stating that nearly 3,000 people died on 9/11 in the worst attack on U.S. soil in American history. The not-so-subtle message was that the ACLU and the courts would be responsible for future attacks and future deaths if the government were prevented from doing what it wanted to do. At a minimum, it was a reminder that the stakes were high.

But the stakes were high for other reasons, as well. In ways no one could have anticipated, we were back to debating first principles that most of us considered well settled. For example, it is hard to imagine a serious discussion about the permissibility of torture prior to 9/11, but it became the subject of heated debate, both legally and politically, after the Bush administration’s “” techniques , including the use of waterboarding.

The terms of that debate were both practical and principled. On a practical level, the government insisted that its resort to torture produced information that helped to foil other terrorist attacks. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence found after reviewing classified evidence that is still not available to the general public.

As a matter of principle, the government did not so much defend its use of torture as claim that its interrogation techniques to torture. That is because even the government conceded that torture violates domestic law, international law, and the enduring values of our constitutional democracy.

The Post-9/11 Docket

The ACLU’s stand against government abuse in the wake of 9/11 led to a substantial increase in membership and contributions. It also placed substantial strain on those increased resources. The ACLU is a multi-issue organization. It defends the rights and liberties enshrined in the Constitution. One of the questions we had to resolve internally was whether to eliminate or curtail our work in other areas in order to support the work that needed to be done after 9/11.

We quickly decided that we could not do that and remain faithful to our mission. We were not prepared, for example, to stop doing prison work or voting rights work or work on behalf of the LGBTQ community. The civil liberties issues in those areas did not disappear because of 9/11, but the government’s response to 9/11 undeniably added a new set of pressing issues to the ACLU’s already broad civil liberties agenda. It was apparent that we needed a strategic plan to confront the challenges we were facing.

Even so, we recognized that we could not do everything, nor did we need to given the work that others were doing. The were the first to reach the Supreme Court and the ACLU filed friend-of-the-court briefs in every one of them. By that detainees at Guantánamo could challenge the basis for their imprisonment by filing a habeas corpus petition in U.S. courts, the Supreme Court prevented what would otherwise have been a legal catastrophe by ensuring that the rule of law did not entirely disappear under the threat of terrorism.

Over the next several years, the ACLU increasingly concentrated its national security work on torture and rendition, surveillance, racial and religious discrimination, and the drone killing of U.S. citizens abroad. The first need in each instance was to find out what the government was doing since so many of its activities were conducted in secret. As famously observed: “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.”

ACLU Executive Director Anthony Romero speaks to reporters after a hearing at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit on Nov. 26, 2006. The ACLU represented Khaled El-Masri (second from left), a German citizen who was disappeared, detained, and abused by the CIA over the course of more than four months in early 2004. The appeals court would ultimately uphold a lower court's decision to dismiss the case on secrecy grounds, and the Supreme Court declined to hear it.

Associated Press/Steve Helber

Perhaps the most successful litigation brought by the ACLU in the early years after 9/11 involved the use of the Freedom of Information Act to expose the government’s torture program. That effort ultimately led to the of tens of thousands of pages of government documents regarding torture, including memos from the Justice Department purporting to provide legal cover for the government’s interrogation practices. Once the nature of those interrogation practices was revealed, the public discussion surrounding torture fundamentally changed.

Sadly, it has proved much more difficult to establish accountability through the judicial process or obtain compensation for the victims of torture, rendition, and drone killing. The courts have not condoned those activities. They have, however, relied on a variety of procedural and jurisdictional rules that have nothing to do with the merits — such as , qualified immunity, and the political question doctrine — to avoid addressing the illegality of the government’s conduct.

Many of the same doctrines have also been used to derail challenges to the government’s surveillance practices, with one notable exception. In response to an ACLU lawsuit, a federal appeals court in New York struck down the government’s practice of routinely collecting telephone metadata — incoming and outgoing telephone numbers, and the duration of each call — for virtually every person in the United States on a daily basis. Following that court ruling, Congress imposed new legal limits on the program, and the government has now, apparently, it entirely. It is worth noting, nonetheless, that we would probably still not know anything about the collection of telephone metadata if Edward Snowden, who is now an ACLU client, had not it.

The ACLU’s centennial offers a moment to reflect on the organization’s past and plan for its future. It can be proud of its steadfast adherence to principle and courageous advocacy in the days, weeks, and years following 9/11. And it should take strength from that experience as it now confronts, and will undoubtedly continue to confront, other civil liberties crises during its next 100 years.

Steve Shapiro was legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union from 1993 - 2016.