Serial, the pop culture podcast phenomenon, isn't just a well-produced and addictive listening experience (though it is both of those things). By questioning the validity of some criminal justice procedures and educating its listeners to ask questions, especially when someone's life is on the line, the podcast has done a great public service: Because the case of Adnan Syed is not particularly unique.

Although the podcast cannot answer whether Adnan is guilty of the murder of Hae Min Lee, it does bring to light serious issues in our criminal justice system like ineffective counsel, the reliability of eye-witness testimony, and how much evidence is needed to convict someone of murder and send them to prison for the rest of their life, or possibly death row.

At the ACLU we listened with rapt attention, noticing mistakes in the defense of Adnan Syed that we commonly come across while doing our work across the nation, often with disturbing results.

One of the first bombshells dropped in Serial is that Adnan had a credible alibi the night Lee was murdered – which was never presented to the jury. We learn that a classmate of Adnan, a young woman named Asia, saw Adnan at the library at the very time the prosecution argued the murder happened in a Best Buy parking lot miles away.

The next revelations were that this alibi information came in a letter that was safely tucked away in the defense lawyer's file. Asia mentions in the letter that she thought there were video cameras in the library that would prove his innocence. Adnan's defense lawyer never requested the video from the library cameras and never even interviewed Asia to follow up. When the reporter on the series, Sarah Koenig, looked into this issue 14 years later after the crime, the library video tape was gone.

We see this familiar pattern across the board: The defense lawyer fails to do a thorough investigation on behalf of his client. When this deficiency is presented to the court, the lawyer's failure is deemed "strategic," or the lawyer is otherwise found to be good enough.

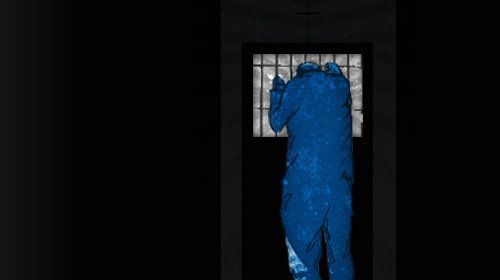

In death penalty cases, lawyers are really playing with fire: Lawyers who were drunk or asleep at trial continued to represent their clients, who are on trial for their very lives. Often times, public defender systems in states are woefully underfunded, which undermines the availability of effective counsel for most of the people who find themselves facing life sentences, or worse.

Just this month, the state of Georgia executed Robert Holsey. Andy Price, Holsey's lead lawyer, drank a quart of vodka every day during Hosley's trial. In that condition, Price told the jury that intellectual disability – an absolute bar to the imposition of a death sentence – was not an issue for Robert Holsey. This was dead wrong. Holsey was in fact intellectually disabled, with an IQ score from age 15 that proved it. Later, once sober, Price told the courts ."

In appeals, the mistakes of lawyers are charged to the defendants. have lost or risked the loss of important federal court review. This didn't happen because there was a lack of evidence proving a reasonable doubt. It happened because their lawyers had missed their filing deadlines. Our criminal justice system presupposes adequate lawyering, without which the system crumbles.

As Serial closes, most of us have formed opinions about Adnan's guilt or innocence. If the answer is not clear, the bigger truth should be: The closer we stand to the criminal justice system, the more obvious its flaws come into focus. In a thin State's case – that probably should never have been tried – the difference between guilt and innocence rests almost entirely on the quality of the defense lawyer.

In cases with serious punishments – especially the death penalty but also life without parole sentences – our justice system must demand that defense counsel do more than show up in the court room.

Learn more about sentencing reform and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .