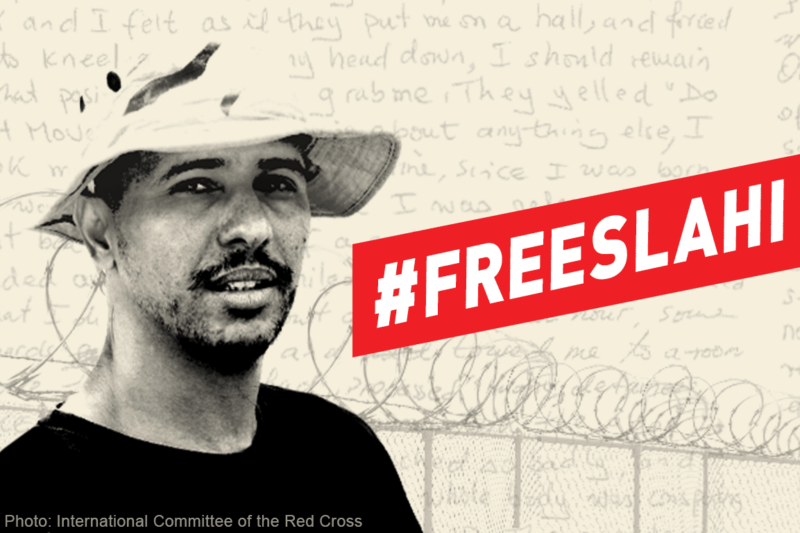

Literary history was made today with the publication of the first-ever book by a still-imprisoned Guantánamo detainee. Mohamedou Ould Slahi's "" was finally published with some redactions after to declassify it.

Slahi– an ACLU client – arrived at the prison in August 2002. His memoir is a terrifying personal story of abduction, detention, and torture in four countries. It is also an American story, and it is ongoing.

Slahi was arrested in his native Mauritania in the fall of 2001, after he turned himself in for questioning. It is clear early on that his arrest was at the behest of the United States, which suspected him of involvement in the "" to bomb Los Angeles International Airport – a suspicion that turned out not to be true. He was soon sent to Jordan, where he was held and tortured for almost eight months. That was in the early days of the CIA's , in which it outsourced the detention and torture of suspects to other countries.

After Jordan, Slahi was briefly held in U.S. military custody in Afghanistan, and then sent to Guantánamo, where he remains today. It was in Guantánamo where he underwent systematic and brutal torture, authorized by former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld himself. He endured a forced abduction, sexual assault, mock execution, beatings, and psychological terror meted out by military interrogators over the course of several months.

Attempts to connect Slahi to the Milennium Plot and, later, to 9/11 have all failed, and the U.S. has never charged him with a crime. The lack of evidence against him has been corroborated by a former Guantánamo chief prosecutor, Col. Morris Davis. (See his .) A federal judge ordered Slahi released in 2010. The government, however, appealed the order, and he remains detained. The ACLU is calling on the government to release him without delay.

Take action: Tell the U.S. government to free Slahi

In the book, we hear directly from Slahi how the absence of evidence of wrongdoing had no effect on his interrogators. The reader follows him as he is nevertheless forced down a sadistic path to false confession, the only way to make the torture stop. The truth became too much to bear:

Whenever I thought about the words 'I don't know,' I got nauseous, because I remembered the words of _________, "All you have to say is, 'I don't know, I don't remember, and we'll fuck you!' … And so I erased these words from my dictionary.

As astonishing as the scope of the abuse is Slahi's enduring warmth, even for his torturers and jailers. His discusses theology and politics with his kinder captors; some teach him English, play chess with him, and bring him books. They all work for the government that has unlawfully detained him for well over a decade. But he views them with extraordinary compassion:

Your family comprises the guards and your interrogators. True, you didn't choose this family, nor did you grow up with it, but it's a family all the same, whether you like it or not, with all the advantages and disadvantages. I personally love my family and wouldn't trade it for the world, but I have developed a family in jail that I also care about. Every time a good member of my present family leaves it feels as if a piece of my heart is being chopped off.

(The Guardian has published additional excerpts, along with an outstanding, partially animated documentary at .)

Slahi's ordeal is at the heart of "Guantánamo Diary," but the book is about much more. It is a chilling story of the United States' worst abuses in the post-9/11 era. It is an account of other countries' complicity in these abuses. It is a terrible example of what happens to innocent people when the rule of law is suspended. In the words of Larry Siems, the book's editor, it is "an epic for our times."

President Barack Obama has made some progress, albeit slow, in transferring detainees out of Guantánamo. His administration can do more. In the case of Mohamedou Slahi, we're calling on Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel not to contest his habeas case.

In April 2010, U.S. District Court Judge James Robinson wrote in his decision that Slahi "must be released from custody." The time is now.

Learn more about indefinite detention and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .