In an increasingly interconnected digital world, strong cybersecurity is essential to safeguarding private data, financial transactions, personal communications, and critical infrastructure. Encryption is one of the few technologies we have that reliably protects sensitive data from identity thieves, credit card fraud, and other criminal activity.

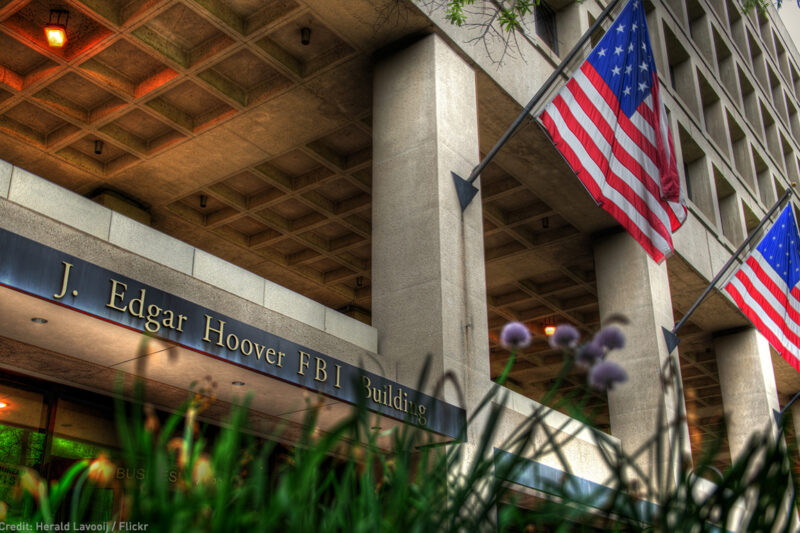

Against this backdrop, high-ranking officials in the FBI and other law enforcement agencies have claimed for years that criminals are using strong encryption to frustrate information gathering in criminal investigations. They have dubbed this the “Going Dark” problem, conjuring a future in which criminals roam free from the reach of law enforcement. These officials say that encryption is too dangerous, and that it must be weakened with government-mandated back doors that would ensure investigators’ access to encrypted data.

FBI Director Christopher Wray that engineers can create back doors that don’t compromise security. But security experts agree that as a back door that opens for the FBI but not for criminals or oppressive governments. Nevertheless, as support for this claim, Wray and other officials said that agents were unable to access data on nearly 7,800 encrypted devices over the last year.

But it’s . The FBI has known for a month that it overcounted the number of devices it was having trouble decrypting by nearly 300 percent. The real number is something less than 2,000.

This latest news drives home that we can’t really trust the FBI when it comes to encryption policy. “Going Dark” is a major FBI policy initiative with one goal in mind: making it easier for the FBI to get whatever information it desires. Given the strenuous objections of the business, security, and civil liberties communities, it could not have been more important for the agency to get this number right — for good policy and for credibility.

This isn’t the only misrepresentation the FBI has made in service of its “Going Dark” campaign. We recently learned that the bureau was not entirely honest during its failed 2016 attempt to force Apple to help it get into the phone of one of the San Bernadino shooters. The FBI said that it had no way of unlocking the phone — but it turns out that some of their own specialists had never been asked whether they could do it. Instead the government sought major legal ruling by leveraging an emotionally and politically charged terrorist attack.

Ultimately, an outside vendor was able to provide a solution, and the FBI had to drop the case. But instead of being happy that investigators were now able to inspect the killer’s phone, a senior FBI official because the case was a great “” for the FBI’s effort to create government-mandated back doors. The ACLU just filed a Freedom of Information Act request seeking information about what the FBI knew during this process as well as records about the government’s use of classified hacking tools in criminal investigations more generally.

Encryption stops crime before it happens, and it also supports privacy, free speech, and human rights. The FBI has held itself out as a responsible arbiter of competing public interests here, but its easy arithmetic error shows it’s not capable of making that more complicated calculation.