This piece originally appeared on the blog at washingtonpost.com.

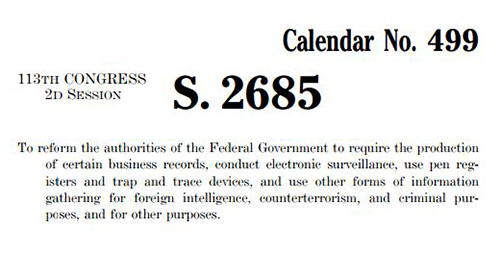

Last week, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) introduced a revamped national security surveillance reform bill called the . Most privacy and civil liberties groups, including the ACLU, . While not perfect, it would create meaningful checks on spying by the and other parts of the intelligence community.

Last week on this site Professor H.L. Pohlman entitled "Might Get Fooled Again?" that civil liberties groups have "overlooked" a key provision that renders the bill "a continuation of the intelligence community's efforts to at best confuse—and at worst, mislead—the American people . . . through the clever use of legalese."

Professor Pohlman is referring to the creation of a new surveillance authority in the bill that would allow the government to seek phone records as they are created, known as prospective collection. The bill would permit government applicants to secure an order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (the FISC) for the production of records "on a daily basis" created "before, on, or after" the date of the application, but only in terrorism cases and only if they meet a higher legal standard than currently exists.

The professor is concerned that the government could simply seek records on an ongoing basis other than "daily"—like weekly or monthly—under the more lenient standard currently housed in Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which allows the collection of "tangible things" that are "relevant" to an intelligence or terrorism investigation.

Given the government's record of stretching surveillance laws to their outer limit and beyond, Prof. Pohlman is absolutely right to be concerned. And there are certainly ambiguities in the language, which we've been saying for a while. But even with the issue the professor raises, the bill would still present an important step toward reform. And it's worth digging into the weeds a bit to see why.

First, while the professor has certainly identified something we'd like to see addressed in the final text, it's not clear the scenario he envisions is the only possible outcome.

Now it is true that the more lenient legal standard in Section 215 has been interpreted by the FISC to permit prospective collection in the phone records program revealed by Edward Snowden. But as detailed by the, the plain language of Section 215 of the Patriot Act—the provision that would be modified by the USA Freedom Act —precludes such a reading (see pages 81 to 87 of ). The FISC was only able to engage in such shoddy legal reasoning because its deliberations are secret, and it only hears the government's side of the argument. The USA Freedom Act includes new transparency provisions to limit such secrecy and would create "special advocates" who, in some circumstances, would be able to argue against attempts to stretch the law.

Additionally, courts are to read statutes—even statutes that are clear on their face, which this is not—to avoid absurd results. By any measure, it would be deeply absurd to create a stricter new regime for prospective daily collection, but to maintain a lenient standard for ongoing minute-to-minute or second-to-second collection. And the bill's affirmative grant of limited prospective collection authority strongly suggests congressional disagreement with the FISC's earlier, expansive legal interpretation.

Second, even if the government does seek phone records prospectively under "tangible things" authority, the bill includes safeguards to prohibit "bulk" collection and limit "bulky" collection, such as all call records for a city or state. The USA Freedom Act would require the government to present a phone number, name, account number or other specific search term before getting the records—an important protection that does not exist under current law. If government attorneys were to try to seek records based on a broader search term—say all Fedex tracking numbers on a given day—the government would have to subsequently go through all of the information collected, piece by piece, and destroy any irrelevant data. The costs imposed by this new process would create an incentive to use Section 215 judiciously.

Finally, as a practical matter, the government is unlikely to seek broad collection authority under the "tangible things" provision. If it uses the new and more limited authority under the USA Freedom Act, the government can get records on all of the individuals in contact with the target and then all of the individuals in contact with those individuals. In the parlance of the FISC, the government can go two "hops" out from the target phone, which it would not be able to do under "tangible things" authority.

Should the bill be tightened to address this and other potential concerns? Absolutely. But it continues to present both an important step forward in reforming these expansive surveillance authorities and a platform on which to build future reform efforts. The concern raised by the professor is a valid one and his careful eye is much appreciated. But, even in the worst case, the bill improves matters—and that's a rare bird in today's Washington.

Learn more about government surveillance and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .