Supreme Court Hears Arguments Today on the Future of Free Speech in Cyberspace

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Washington, D.C. -- One year after the American Civil Liberties Union filed a legal challenge to a law censoring free speech in cyberspace, the U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral argument in a case that will likely determine the future of free speech into the next century.

The ACLU's suit, filed on February 8, 1996, challenges censorship provisions of the Communications Decency Act (the "CDA") aimed at protecting minors by criminalizing so-called "indecency" on the Internet. The government appealed the case to the High Court after a federal three- judge panel ruled unanimously last June that the law unconstitutionally restricts free speech. A later suit, filed by the American Library Association (ALA v. DOJ), was consolidated with Reno v. ACLU in the lower court.

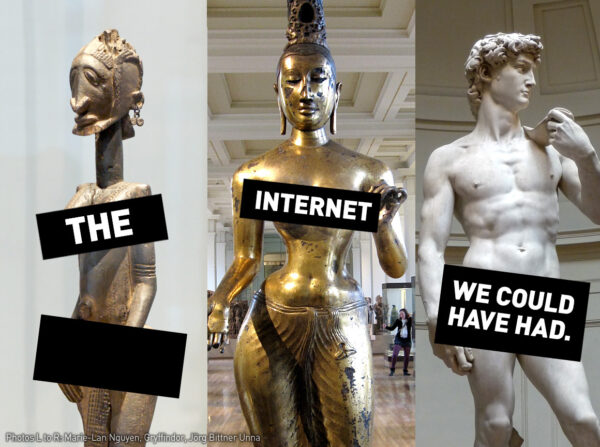

"Freedom of speech took a great leap forward with the expansion of the Internet, presenting not only Americans but the world with an unprecedented opportunity to communicate equally," said Christopher A. Hansen, ACLU national staff attorney and Reno v. ACLU lead counsel. "It is ironic, to say the least, that this democratizing, global medium is being censored by the very country that is supposed to be a beacon of freedom."

Reno v. ACLU presents the Court with its first opportunity to consider how traditional free speech principles should be applied to the Internet, Hansen said. The case has been on the fast track from the beginning, when Congress, anticipating legal challenges and desiring a speedy resolution, wrote into the CDA an expedited path to the Supreme Court's door.

Beginning this morning at 10:00 a.m., lawyers representing the ACLU/ALA plaintiffs and the government will each have thirty minutes to present their arguments before the Court. The government, as the appellant, will appear first, and may choose to reserve some time for rebuttal. The defendants, arguing second, do not have this option.

After emerging from the courtroom for the traditional "Supreme Court steps" press briefing, ACLU lawyers and plaintiffs will go live online in a "cybercast" news conference to offer in-depth analysis and commentary on the arguments before the High Court. In an Internet first, the ACLU is also planning to post transcripts of the Supreme Court arguments on its website later today.

Much speculation has been directed at the degree to which the nine justices are familiar with the medium. However, as noted by ACLU Legal Director Steven R. Shapiro, the extensive findings of fact contained in the lower court decision constitute a kind of Internet ?primer.'

"We expect the lower court's findings to be enormously helpful in guiding the Court as to the nature of communication and content in the cyberspace medium," he said. "Among other things, the trial in this case conclusively showed that there are ways to empower parents that do not set up the government as a supercensor of the Internet."

Notably, Shapiro said, 334 of the 409 separate fact-findings adopted by the trial court were derived from stipulations (mutual agreements as to facts) submitted by the plaintiffs and defendants. Thus the majority of the facts necessary to the court's ruling were not disputed by the government.

Among the court's findings:

- the CDA "will almost certainly fail to accomplish the government's interest in shielding children from pornography on the Internet," in part because "nearly half of Internet communications originate outside the United States."

- the government failed to meet its burden of establishing a compelling interest in blocking all minors' access to all online communications.

- the record demonstrates numerous alternative means of accomplishing the government's purpose more effectively and less restrictively than an outright criminal ban, through parental use of blocking software and the development of other technology that allows for voluntary screening.

The kind of "indecency" identified as potentially criminal by government witnesses in the lower court included Internet postings of the photo of the actress Demi Moore naked and pregnant on the cover of Vanity Fair, and any use online of the famous "seven dirty words." In addition, the CDA would put at risk much of the socially valuable material posted online by the plaintiffs, including the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, Stop Prisoner Rape, Human Rights Watch and Critical Path AIDS Project. The ACLU argued that minors are entitled to have access to such socially valuable information.

"As one of the lower court judges noted, laws based on a desire to protect children are as dangerous as they are compelling," said Ann Beeson, ACLU national staff attorney and a member of the Reno v. ACLU legal team. "Recognizing the importance of instilling democratic values in children, he wrote that "regulations that 'drive certain ideas or viewpoints from the marketplace' for children's benefit, risk destroying the very 'political system and cultural life,' that they will inherit when they come of age. We hope the Supreme Court will agree."

A decision by the Court is expected in July. In the meantime, the lower court's preliminary injunction against the CDA still stands and online communicators are safe from federal prosecution.

However, the ACLU's Ann Beeson noted, a similar "CDA-type" law passed late last year in New York state puts "netizens" everywhere at risk all over again. Moving to protect Internet users from criminal prosecution, the ACLU and the New York Civil Liberties Union filed a challenge to the law in January, asking the state to agree not to seek prosecutions until the resolution of the case. The attorney general's office refused, and the New York case is due to go to trial on April 3.

A favorable decision by the Supreme Court is likely to reinforce the ACLU's argument that the New York law -- and other Internet censorship laws passed in Virginia, Georgia and elsewhere -- unconstitutionally restricts free speech, Beeson said.

The 20 plaintiffs in Reno v. ACLU are: American Civil Liberties Union, Human Rights Watch, Electronic Privacy Information Center, Electronic Frontier Foundation, Journalism Education Association, Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, National Writers Union, ClariNet, Institute for Global Communications, Stop Prisoner Rape, AIDS Education Global Information System, BiblioBytes, Queer Resources Directory, Critical Path AIDS Project, Wildcat Press, Justice on Campus, Brock Meeks dba CyberWire Dispatch, the Safer Sex Web Page, The Ethical Spectacle, and Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Lawyers for the ACLU are Christopher Hansen, Ann Beeson and Marjorie Heins of the national office; Steven R. Shapiro, the ACLU's national Legal Director; and Stefan Presser, Legal Director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania.