Pauli Murray's Indelible Mark on the Fight for Equal Rights

When Pauli Murray applied to the University of North Carolina in 1938, she received a reply from the dean: “Under the laws of North Carolina, and under the resolutions of the Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina, members of your race are not admitted to the university.”

When she applied to Harvard Law School in 1944, the admissions committee told her, “Your picture and the salutation on your college transcript indicate that you are not of the sex entitled to be admitted to Harvard Law School.”

Discriminated against from childhood because of her race or gender or both, Pauli Murray would take her indignation, her hurt, and her intelligence to the ACLU board of directors in 1965. Once there, she played a key role in turning the ACLU’s attention to gender inequality, and helped pave the way for Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Women’s Rights Project.

Anna Pauline Murray was born in Baltimore on November 20, 1910, the descendant of African-Americans, Caucasians, Native Americans, slaves, and slaveowners. Her mother died when Murray was three and her father would die in a psychiatric institution. Murray was sent to Durham, North Carolina to live with her aunt Pauline Fitzgerald, who adopted her.

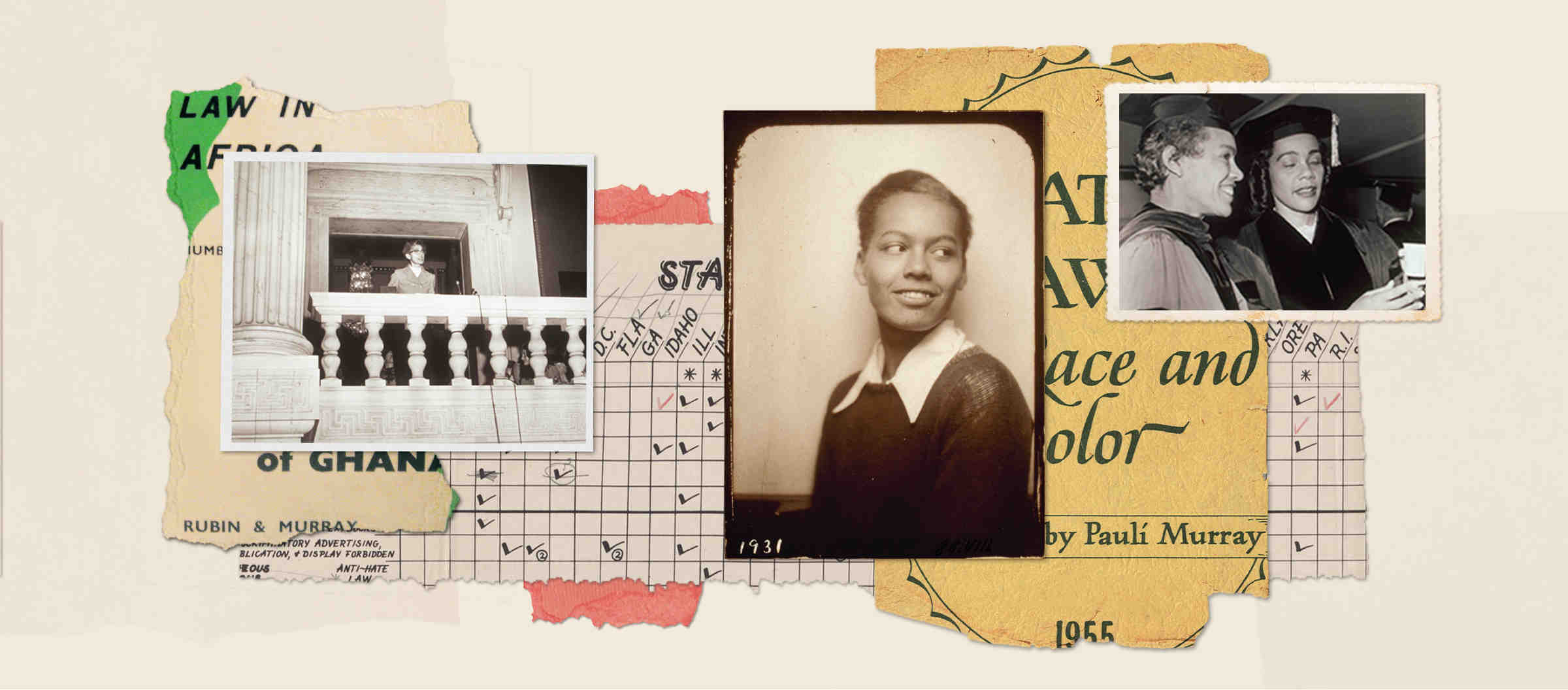

Pauli Murray in 1931

The Schlesinger Library. By permission of the Pauli Murray Foundation and the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency. All rights reserved.

Aunt Pauline taught at a segregated school, which is where Murray was educated. The young Murray couldn’t avoid segregated schooling, but she could sometimes circumvent segregation elsewhere. She refused to get on Jim Crow streetcars, opting instead to walk or ride her bike. Murray didn’t go to the movies, because she would not climb the back stairs to the balcony. Instead, she read voraciously.

Murray refused again when she graduated from high school, declining to apply to the North Carolina College for Negroes. Hoping to get into a Northern university, she traveled to New York City but was told there that because her high school taught only through the 11th grade, she would first have to complete her education. Murray went to Richmond Hill High School in Queens, graduated, and then had to work for a year to earn enough money so that she could continue living in New York. Admitted to Hunter College in 1929, she became one of four African-Americans in a class of 247. She continued to work throughout college, earning so little in those years of the Depression and having to move so frequently that she lost 15 pounds during her first year of college and suffered from malnutrition and ill health for the rest of her life.

While she was at Hunter, Murray began calling herself Pauli rather than Pauline. Convinced she was a man in a woman’s body, she tried unsuccessfully for years to get hormone therapy that would aid her transition to her true self. In the days when “proper” women wore skirts, Pauli wore pants, cut her hair short, and dressed like a Boy Scout whenever she traveled. Her inability to fully live as or acknowledge publicly the gender that felt true to her plagued her throughout her life, adding to her sense of being an outsider.

Always desperate for a livable income, during the 1930s-1950s she held a wide variety of low-wage short-term jobs, primarily with left-wing organizations. Then in 1935 she went to work for the Works Progress Administration and, in 1936, its Workers’ Education Project. She was startled to meet white students as deprived as black students and realized, as she wrote in , “that Negroes were not alone but were part of an unending struggle for human dignity the world over ... Seeing the relationship between my personal cause and the universal cause of freedom released me from a sense of isolation, helped me to rid myself of vestiges of shame over my racial history.”

Her experiences made Murray eager to study sociology. It was when she applied to the University of North Carolina to do so that she received its rejection letter. She was particularly incensed because in accepting an honorary degree from the university, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had praised UNC as “representative of liberal teaching and liberal thought.” Never one to , Murray fired off indignant letters to newspapers as well as to FDR and sent copies to both Walter White at the NAACP and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

White forwarded her letter to assistant special counsel Thurgood Marshall, who declined to file a case because Murray’s years living in New York complicated her instate resident’s right to attend UNC. Eleanor Roosevelt, however, showed the letter to her husband and wrote back to Murray, beginning a correspondence and then a friendship that lasted until the First Lady’s death. She called Murray a “firebrand” and “one of my finest young friends.”

In March 1940, Murray and an African-American friend traveled through Virginia by bus on their way to North Carolina. The friend became ill during the trip and the two women moved from broken seats in the back of a bus to better ones, which resulted in their arrest. This time the NAACP did take their case, seeing it as an opportunity to challenge Virginia’s segregated transportation system. The judge in the case convicted them of disorderly conduct rather than of violating the segregation laws, however, and the NAACP, unable to leverage the suit as an assault on segregation, declined to take it further.

A few months later, the Workers Defense League, part of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, sent Murray to Virginia to try to save the life of a Black sharecropper convicted of murdering a white farmer. During the unsuccessful effort to seek contributions to fund the sharecropper’s appeal, she met Howard University Law School professor and civil rights activist Leon Ransom. Impressed by her passion and eloquence, Ransom suggested she consider law school, and promised he would get her a work scholarship at Howard. In September of 1941, Murray began her legal education.

Murray was the only woman in her class at Howard. It was there that she “first became conscious of the twin evil of discriminatory sex bias, which I quickly labeled Jane Crow,” she recalls in her memoir. Even Ransom accepted her exclusion from an event for men, and “the discovery that Ransom and other men I deeply admired because of their dedication to civil rights, men who themselves had suffered racial indignities, could countenance exclusion of women from their professional association aroused an incipient feminism in me long before I knew the meaning of the term ‘feminism’… I had entered law school preoccupied with the racial struggle and single-mindedly bent upon becoming a civil rights attorney, but I graduated an unabashed feminist as well.”

Pauli Murray in December 1946.

Associated Press

Still, most of her attention was focused on racial discrimination. Unable to afford anywhere else to live, in 1943 she moved into a powder room in Howard’s undergraduate Sojourner Truth Hall. Her room quickly became the organizing hub for an assault on Washington’s segregated restaurants. Murray and fellow students planned sit-ins and picket lines and managed to integrate two restaurants before the university administration called a halt to the protests, fearing funding retribution from Congress.

One of Murray’s courses at Howard was a civil rights seminar. The other students hooted when she argued that the equal protection clause should be used for a frontal assault on Plessy v. Ferguson, rather than the NAACP’s step-by-step strategy of chipping away at the separate but equal doctrine. She bet a skeptical Professor Spottswood Robinson $10 that Plessy would be overturned within 25 years, and her last paper for Howard proposed a way to use the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments for that purpose. Robinson kept the paper and referred to it a decade later when he and the NAACP were preparing Brown v. Board of Education.

Murray graduated first in the class of 1944 and was awarded a foundation fellowship to be used for graduate study. That’s when she was turned down by Harvard Law School, but was accepted by Berkeley’s Boalt Hall, where she earned a master’s degree in law.

Returning to New York in 1946, Murray applied for admission to the New York bar, discovering that it viewed her with suspicion in part because she had worked for so many left-wing organizations. Worse still, the 36-year-old Murray had held 23 jobs and lived in 38 different places. The bar committee seemed unable to understand the life of an impoverished African-American woman desperately trying to earn a living and find somewhere affordable to live. Eventually, however, she was admitted, and scraped by for two years, working in the offices of different black solo practitioners.

Murray was hired by the women’s division of the Board of Missions of the Methodist Church in 1948 to pull together a compilation of state segregation laws. Thurgood Marshall called the resultant massive volume, “States’ Laws on Race and Color,” the “Bible” of civil rights litigators.

Pauli Murray as a Senior Lecturer Ghana Law School Accra, Ghana Standing in front of the Ghana Law School building, Spring 1960.

A series of jobs followed. In 1960 Murray jumped at the chance to become a senior lecturer at the Ghana School of Law. She and Leslie Rubin, a fellow lecturer, soon produced “The Constitution and Government of Ghana,” a 310-page treatise on and critique of the newly independent nation’s laws. The government did not appreciate the critique part, and Murray thought it best to leave. In 1961, she secured a fellowship to work at Yale University for a doctorate of laws. There she was astonished to discover that her courses made no mention of gender discrimination. Murray became the first African-American to receive Yale’s degree of Doctor of Juridical Science.

In 1962, Murray received a telegram from Eleanor Roosevelt that would eventually lead her to the ACLU. President John F. Kennedy had created the first Commission on the Status of Women in 1961, chaired by the former First Lady. Roosevelt asked Murray to serve on its Committee on Political and Civil Rights, charged with the question of how best to use the nation’s legal and political systems to combat gender discrimination.

The committee was divided on the question of whether the proper approach was litigation under the Fourteenth Amendment, or work on behalf of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment. Murray managed to persuade the committee to write a report that did not rule out support for the ERA but emphasized litigation under the equal protection clause. A copy of the report went to the ACLU, where the staff and board leader Dorothy Kenyon identified it as a roadmap to begin combatting gender inequality.

Murray and Kenyon became a team, determined to put gender discrimination on the ACLU’s agenda. “Pauli and I, she out in front with her double discriminations, I at the rear with my years of experience behind me and the prayer that the younger ones may start out differently from us,” Kenyon later recalled.

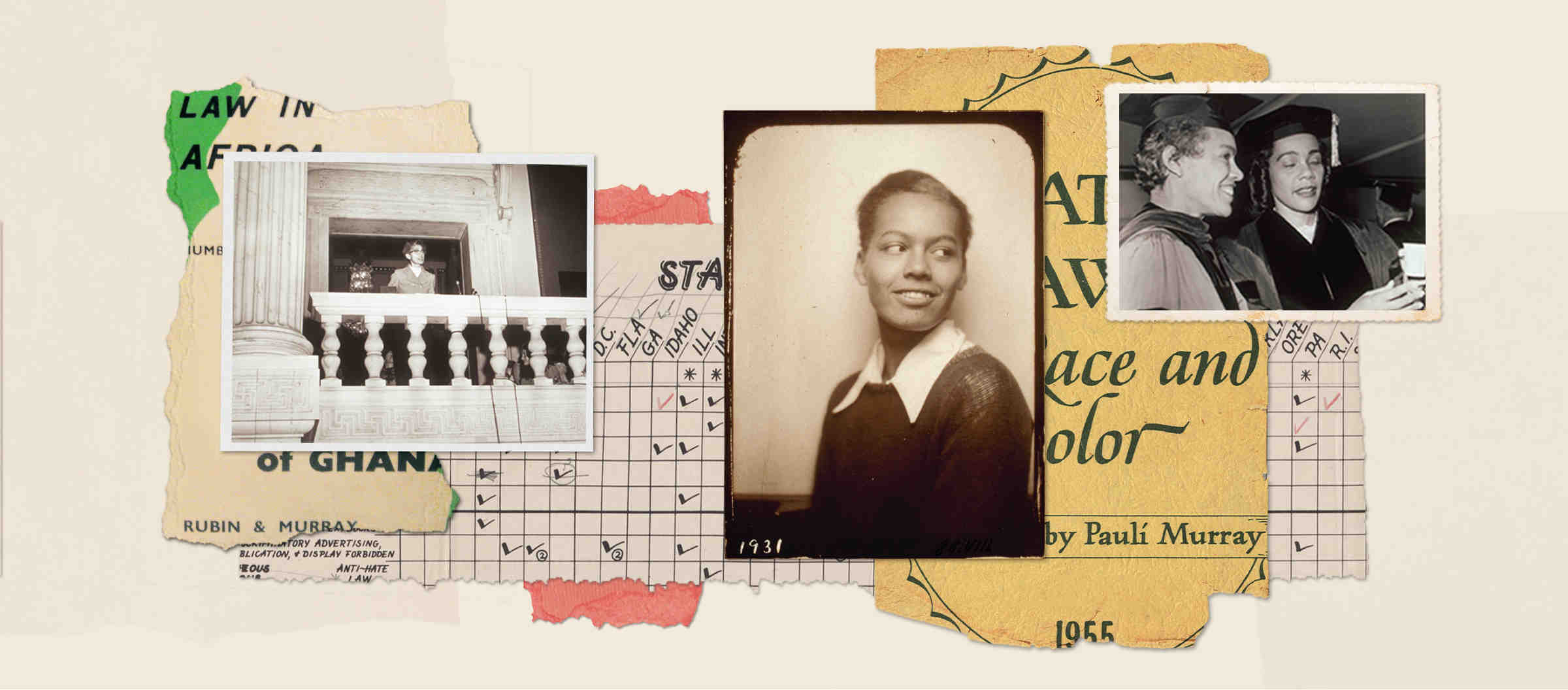

Portrait of Pauli Murray, March 1964

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe/Harvard

Eleanor Holmes Norton, a former ACLU attorney and later a member of Congress, has described Murray as “a feminist when feminists could not be found.” The same could be said of Dorothy Kenyon. An ACLU board member since 1930, she had been pushing the male-dominated ACLU for decades to use the Fourteenth Amendment to attack gender discrimination. In 1965, Kenyon and James Farmer successfully nominated Murray for the ACLU board. Murray was immediately asked to work with Kenyon on the case of , in which the ACLU challenged Alabama’s exclusion of African-Americans and women from juries. Murray wrote the part of the ACLU’s brief demonstrating the intersection of race and gender discrimination, arguing that laws differentiating on the basis of gender should be subjected to the same “skeptical scrutiny” that the federal courts were giving to similar race laws.

In making their argument, the two women appended to the brief an article entitled “.” It was written by Murray and Mary Eastwood, an attorney Murray met during their work on the Committee on Political and Civil Rights. The ACLU won White v. Crook in the federal district court, and Alabama declined to appeal.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

In spite of its participation in White v. Crook, the ACLU’s equality litigation still focused almost entirely on race. Murray, Kenyon, and the very few other women on the ACLU board had an uphill fight in raising the consciousness of many of their male counterparts. In September 1970, for example, the board was set to discuss the question of whether or not to support the Equal Rights Amendment. After receiving their materials for the meeting, Kenyon and Murray sent a telegram to the entire board.

“Board materials include paper on Equal Rights Amendment written by four men law professors and (inadvertently) not one syllable from any women,” it said. “We are aghast at such gallant effrontery. Hell hath no rage greater than a woman scorned. Beware of more materials.”

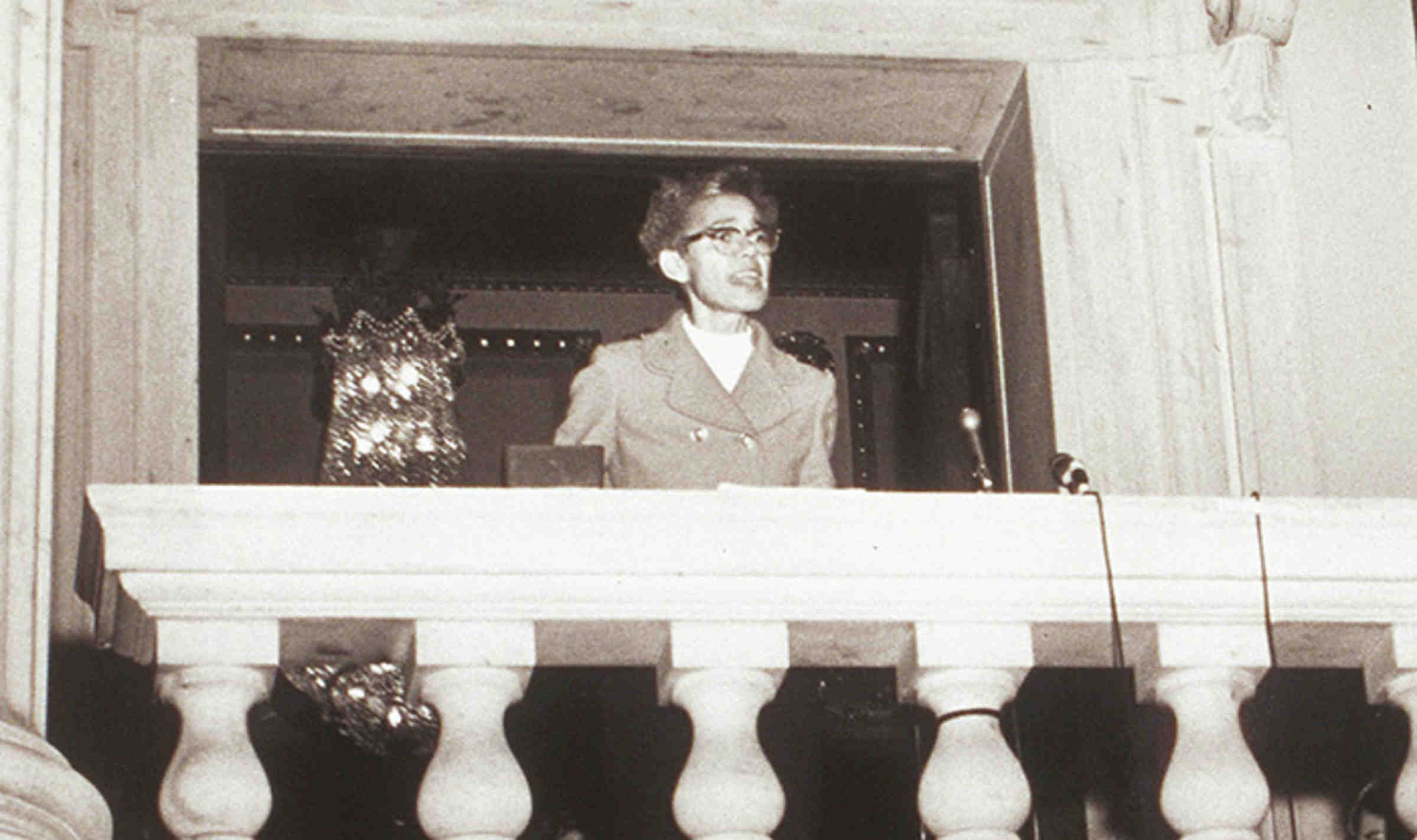

Pauli Murray, speaking at the Capital, Rhode Island Women’s Day, Oct 17, 1971

The Schlesinger Library. By permission of the Pauli Murray Foundation and the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency. All rights reserved.

The ACLU had held back on endorsing the ERA, primarily at the urging of labor leaders who feared that its passage would undo the protective legislation for women that was enacted in the years before the courts were willing to accept the idea of protections for all workers. By the 1970s, however, with inclusive legislation in place around much of the country, unions were ready to join the fight for ERA. Kenyon and Murray took the victory in White, and the “Jane Crow” article, to the ACLU board. They urged a two-pronged strategy, supporting both the ERA and gender equality litigation under the equal protection clause. Just as the NAACP and ACLU had long used the clause to litigate against racial discrimination, they argued, the organization was morally obligated to do the same when women faced discrimination.

Dr. Pauli Murray, then a law professor at Brandeis University, arrives for classes in Waltham, Mass. on Sept. 27, 1971.

AP Photo/Frank C. Curtin

Murray was, of course, uniquely placed to demonstrate the relationship between discrimination on the basis of race and on account of sex, both in the ACLU and elsewhere.

“As a Negro woman,” she wrote in her memoir, “I knew that in many instances it was difficult to determine whether I was being discriminated against because of race or sex.”

In September 1970 she testified on behalf of the ACLU before the Senate committee considering ERA. “The Negro woman has suffered more than the addition of sex discrimination to race discrimination,” she declared. “She … remains on the lowest rank of social and economic status in the United States. The black male, at least, can identify and aspire to the dominance of his white counterpart.”

Murray and Kenyon were victorious in September, as the ACLU board voted to make women’s rights a top priority. A year later the board created the Women’s Rights Project. Aryeh Neier, then the ACLU’s executive director, asked law professor Ruth Bader Ginsburg to lead it. The rest is history.

In 1971, when Ginsburg submitted her first gender equality brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in Reed v. Reed, she put Pauli Murray and Dorothy Kenyon’s names on its cover page. Neither had actually worked on the case, but Ginsburg recognized that their delineation of the connection between race and gender, and of the way to use the equal protection clause to litigate for gender equality, were crucial steps that paved the way.

Pauli Murray remained on the board until 1974. She left when she began the studies that led to her ordination as the first African-American woman Episcopal priest. She died in 1985, at age 74.

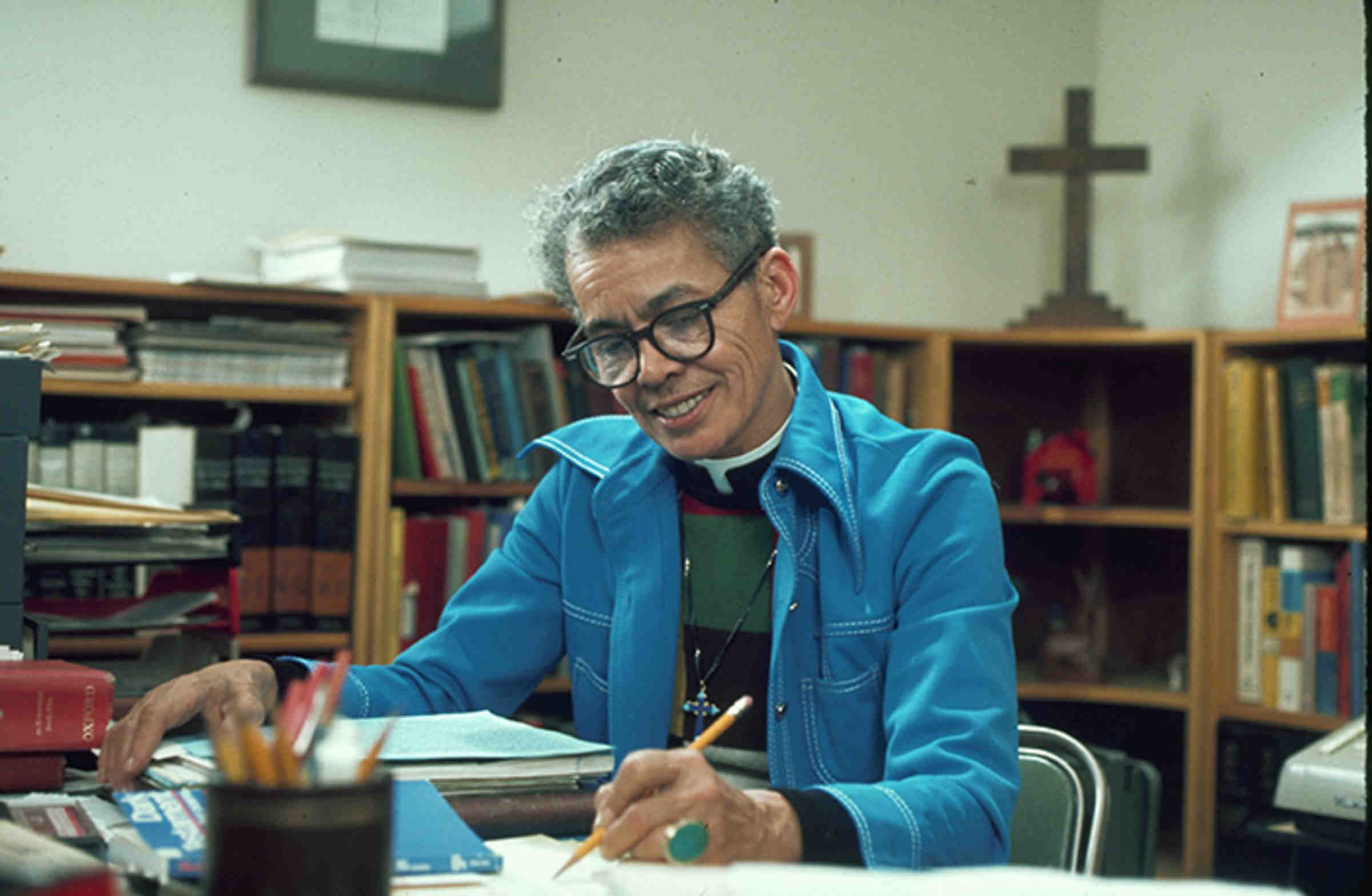

Portrait of Rev. Pauli Murray seated at her desk, April 1977.

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe/Harvard

Murray wrote and published poems throughout her adult life. Perhaps her best-known is “Dark Testament,” which includes the lines that could be her epitaph:

I speak for my race and my people -

The human race and just people.

Further Reading

by Pauli Murray

, by Rosalind Rosenberg

“” by Kathryn Schulz.

Philippa Strum is a political scientist specializing in American constitutional law and civil liberties. A longtime lay leader of the ACLU, her numerous books include "When the Nazis Came to Skokie" and "Speaking Freely," about two of the ACLU's seminal free speech cases; "Women in the Barracks," the story behind the Supreme Court's gender equality decision in the Virginia Military Institute case; and "Mendez v. Westminster," the tale of the first time a federal court declared "separate but equal" to be unequal — a case brought by Mexican-Americans and decided eight years before Brown v. Board of Education.