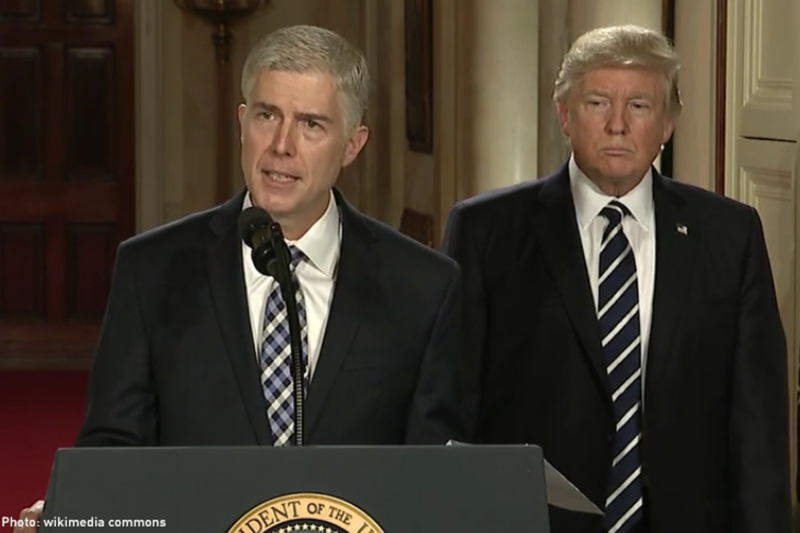

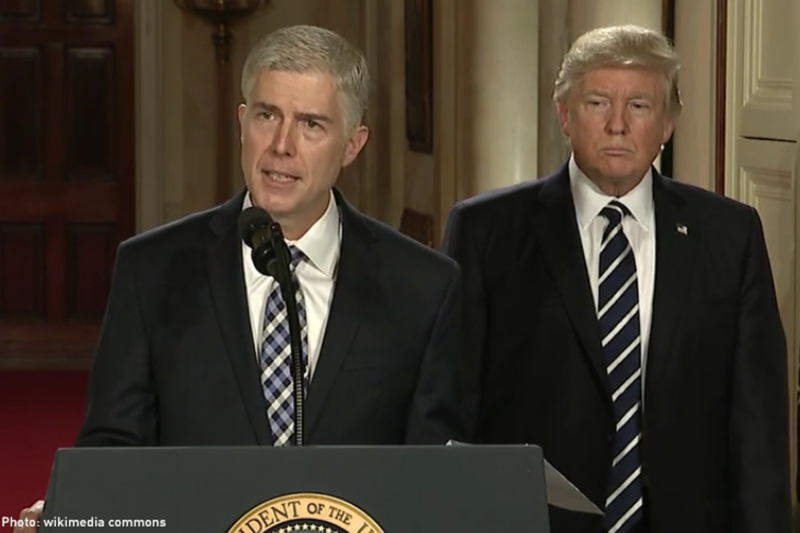

If We Care About Abortion, Asking Judge Neil Gorsuch His Opinion on Roe v. Wade Is Not Enough

Now that President Trump has nominated federal judge Neil Gorsuch to be considered for the Supreme Court, one question on everyone’s mind is, “What’s his position on Roe v. Wade?” That is a shorthand way of asking, “Does he believe that a woman has a constitutional right to abortion.” That is a critically important question, but often it’s not the most important one regarding abortion rights.

Here’s why.

Right now there are five justices on the Supreme Court who agree that the Constitution protects a woman’s right to abortion. The possibility that the court would uphold an outright ban on abortion seems very remote — unless and until President Trump is able to nominate a second justice. But there are many, many things that the government can do short of an outright ban that can put an abortion out of reach for women.

Since the 2010 elections, state politicians have passed more than 338 restrictions on abortion, 50 in 2016 alone. To prevent these unconstitutional laws from harming women, doctors and health centers — along with the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, and the Center for Reproductive Rights —routinely go to court to challenge these restrictions. And to get them struck down, we generally must show that the restriction imposes what the Supreme Court, in its 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, termed an “undue burden.”

In Casey, the court explained that “[a]n undue burden exists, and therefore a provision of law is invalid, if its purpose or effect is to place a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion before the fetus attains viability.” In other words, the restriction must have a legitimate purpose, such as protecting a woman’s health not just preventing abortion. The restriction cannot impose unwarranted barriers to a woman’s ability to actually get an abortion.

There are many, many things that the government can do short of an outright ban that can put an abortion out of reach for women.

Since the Casey decision, the real question in the courts has not been whether there is a right to an abortion at all, but rather what constitutes an “undue burden.” How far can the government go in restricting a woman’s right?

It turns out that politicians around the country have shown an extraordinary appetite for seeing just how far they can push the courts on this question. Politicians have passed laws that shut down most of the clinics in a state; require every woman who has a miscarriage or an abortion to bury or cremate the embryo or fetus; force doctors to show, and describe in detail, to women the pictures of their ultrasound as a condition of getting an abortion; force a woman to talk about her decision with a staff at an anti-abortion organization; ban abortion as early as six weeks of pregnancy — before many women even know they are pregnant; ban abortion after the first trimester; prevent a woman from having an abortion because she has learned that the fetus has a severe medical condition; and the list goes on and on.

The only protection women in many states have against being subject to laws like these is the courts and, in some instances, the Supreme Court.

Take, for example, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the case that the Supreme Court decided in June. In that case, Texas passed two laws that forced doctors and health centers that provide abortions to comply with extraordinarily burdensome — and in many cases impossible — standards that providers of comparable medical care were not required to meet. The result would have been that 75 percent of the clinics in Texas would have been forced to close.

Even though the evidence and leading medical groups made clear that these laws harmed women’s health rather than improved it, the appeals court upheld them. As long as the legislature could have rationally speculated that the requirements might do some good, the court said that was enough to justify the closure of three-fourths of the clinics in the state. Incredibly, the appeals court ruled this way all the while purporting to recognize that women have a constitutional right to abortion.

In a 5-3 decision, the Supreme Court rejected this topsy-turvy view of constitutional rights and came to what should have been an unsurprising conclusion: If a state is going to burden a woman’s access to abortion, it must come forward with actual evidence to show that the benefits of the law outweigh the burdens. Texas had no such evidence, so the laws constituted an undue burden, and the Supreme Court struck them down.

The Texas case provides a stark example of how drastically some politicians and some courts will go to restrict a woman’s ability to get an abortion, all the while paying lip service to Roe v. Wade. So, by all means, we should ask whether Gorsuch believes that a woman has a constitutional right to abortion at all. But if we care about whether a woman can actually get an abortion, we cannot stop there. We must go further to understand what the nominee thinks are the contours of that right.

Here a few of the questions the Senate should ask Gorsuch.

- Does Gorsuch believe that the Supreme Court got it right in Whole Woman’s Health or would the nominee allow the government to shut down clinics based on “alternative facts?”

- Does Gorsuch believe that the government can constitutionally impose laws like mandatory ultrasound and fetal burial requirements for no purpose other than to shame and stigmatize women?

- Does Gorsuch believe that the government can constitutionally block Medicaid from covering abortion for eligible women?

- Does Gorsuch believe that the government can constitutionally block women from seeking any care, including birth control and cancer screenings, at Planned Parenthood because Planned Parenthood also provides abortions?

Only when we get the answers to questions like these can we understand Gorsuch real views on abortion.