This morning, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Town of Greece v. Galloway, a First Amendment challenge to a New York town's practice of solemnizing its local board meetings with Christian prayer. The argument revealed the weak constitutional footing on which the town stands when it argues that it may invite local clergy, the vast majority of whom are Christian, to deliver official invocations that are overwhelmingly Christian. It also served as a stark reminder of how the Supreme Court has failed citizens who are non-believers when it comes to this issue.

Posing the first question of the day, Justice Kagan asked whether similar official prayers would be permissible at Court sessions or congressional hearings. The town's lawyer responded in the only way a reasonable person could. He conceded that such prayers – those that invoke explicitly Christian beliefs – would indeed be unconstitutional, but argued that the town's prayers were different because they reflect a long history of legislative prayer, which includes state legislatures and the First Congress. Pressed further by Justice Kennedy to provide a justification for the prayers other than tradition, the town's lawyer, not surprisingly, came up short.

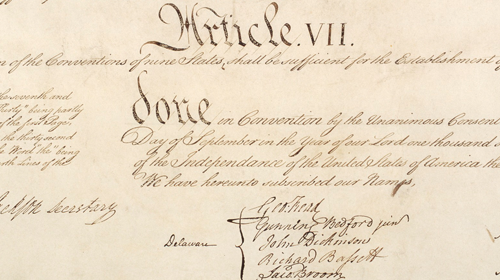

In fact, as the ACLU argued in its friend-of-the-court brief, tradition -- standing alone -- is a poor reason for flouting a fundamental principle of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment: The government should remain neutral on matters of faith and may not promote religion over non-religion. When elected officials violate this maxim by imposing official prayer at meetings, especially local governmental meetings, it casts those who don't subscribe to the promoted beliefs as outsiders, second-class citizens who must pay a steep price in spiritual terms for daring to exercise the right of participatory democracy.

During the , Justice Kagan eloquently summed up the problem:

[H]owever we worship, we're all equal and full citizens. . . . And that means that when we approach the government, when we petition the government, we do so not as a Christian, not as a Jew, not as a Muslim, not as a nonbeliever, only as an American. And what troubles me about this case is that here a citizen going to a local community board, supposed to be the closest, the most responsive institution of government that exists, and is immediately being asked, being forced to identify whether she believes in the things that most of the people in the room believe in, whether she belongs to the same religious idiom as most of the people in the room do. And it strikes me that that might be inconsistent with this understanding that when we relate to our government, we all do so as Americans, and not as Jews and not as Christians and not as nonbelievers.

For the very same reason identified by Justice Kagan, in its brief, the ACLU urged the Court to overrule Marsh v. Chambers, a 1983 decision authorizing state legislatures to open sessions with nondenominational prayer. Even if official prayers are nondenominational, they still exclude huge swaths of the citizenry, including non-believers, polytheists, and those whose religion condemns government appropriation of prayer. This fact was repeatedly recognized during the oral arguments. However, instead of treating the alienation of these groups from the democratic process with the concern it deserves, their exclusion was considered a given and, at times, a punch line. Laughter filled the room, for example, as the justices pondered what type of prayer would be acceptable to an atheist.

If a majority of the Court is not willing to take the leap of empathy that would be required to reverse Marsh and respect the rights of these excluded groups to participate in their local government without the burden of official prayer, the Court must, at the very least, do all it can to limit the exclusionary impact of such prayers by reaffirming that Marsh requires that legislative invocations remain nondenominational and, therefore, as inclusive as possible of those of varying faiths. If the Court fails to do so, millions of minority-faith adherents across the country, including Jews, Muslims, and Sikhs, will also be rendered second-class citizens and denied the experience of full citizenship that is so vital to our pluralistic democracy. That would be no laughing matter.

Learn more about the separation of church and state and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts,, and .