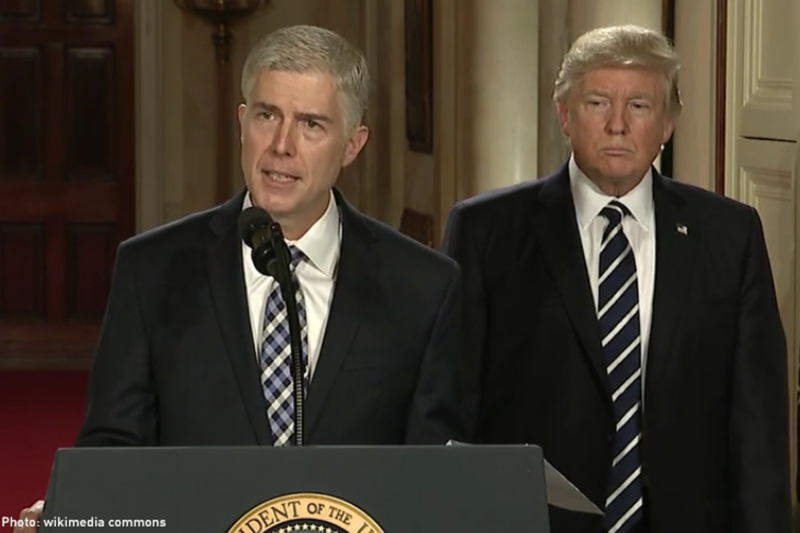

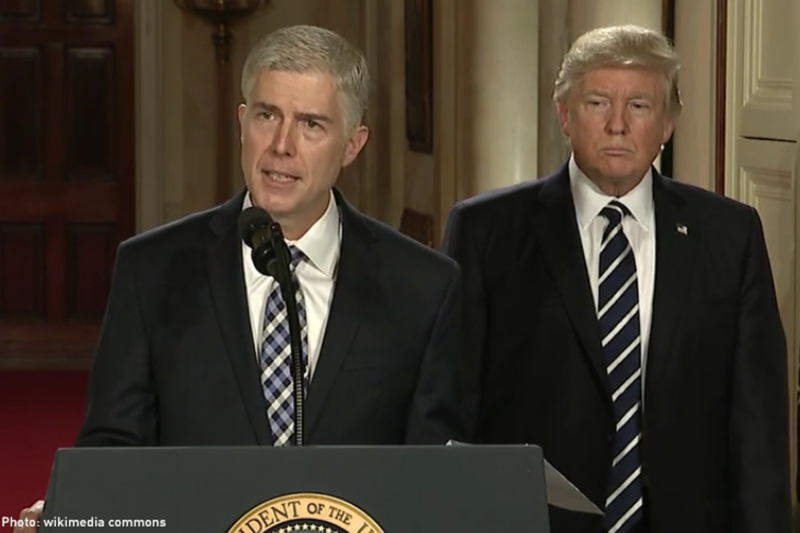

Does Donald Trump's Supreme Court Nominee Believe Employees Should Bear the Costs of Their Employer's Religious Beliefs?

This post originally appeared at .

Religious freedom protects the right to our beliefs. But does it protect the right of institutions to discriminate? The ACLU, a staunch defender of religious liberty, says no. The answer for Supreme Court nominee Judge Neil Gorsuch appears to be yes. It is the province and duty of the Senate to press Judge Gorsuch on his stance during his confirmation hearings, as this question promises to be central to significant cases likely to come before the court in the near future.

The opinions of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit that Judge Gorsuch joined and authored addressing Religious Freedom Restoration Act challenges to the contraceptive coverage rule of the Affordable Care Act raise troubling questions about his understanding of religious liberty, principles of equality, and their intersection.

Three points are worth noting.

First, and most significant, in the Hobby Lobby case, the Tenth Circuit, ruling en banc, gave short shrift and even embraced the harms to women that would result were the rule enjoined as to Hobby Lobby. The court acknowledged that women denied coverage — in that case to four methods of contraception — would suffer an economic burden but went on to say, “Accommodations for religion frequently operate by lifting a burden from the accommodated party and placing it elsewhere.” In other words, the court, with Judge Gorsuch joining, accepted that employees should bear the cost of their employer’s religion.

That’s a position the Supreme Court declined to embrace in its Hobby Lobby decision. The court affirmed the Tenth Circuit and ruled for the arts and crafts giant, but its ruling, unlike that of the Tenth Circuit, rested on the premise that the government could extend the accommodation it provided to religiously affiliated nonprofit entities to for-profit companies. Critically, that accommodation was designed to ensure that employees would continue to receive seamless coverage of contraception from the insurer. In the court’s opinion, the effect then on “the women employed by Hobby Lobby … involved in these cases would be precisely zero.” The same cannot be said under the Tenth Circuit’s reasoning, which Judge Gorsuch joined.

Second, the Tenth Circuit decision is noteworthy for how it understands discrimination. In ruling for the plaintiff, the court stated that the government had not demonstrated how mandating compliance by Hobby Lobby in particular furthered the compelling state interest in gender equality served by the contraceptive rule. That reasoning fails to appreciate that every act of discrimination is harmful and undermines the promise of equality. We understand that readily in other contexts: No one would similarly argue that the federal government was not adopting the least restrictive means when it required Piggie Park — a barbecue franchise — to comply with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 over religious objection. If we believe in gender equality, the same principle should apply in the context of Hobby Lobby.

It is the duty of the Senate to press Judge Gorsuch on his stance on religious liberty and discrimination during his confirmation hearings.

Third, Judge Gorsuch’s concurrence in Hobby Lobby readily embraces claims of complicity as giving rise to an asserted substantial burden within the meaning of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. He writes that “[a]ll of us face the problem of complicity . . . For some, religion provides an essential source of guidance both about what constitutes wrongful conduct and the degree to which those who assist others in committing wrongful conduct themselves bear moral culpability.”

But what are the limits to this reasoning? Is there no difference, for example, for purpose of RFRA’s substantial burden claim between doing paperwork for someone placed on death row or administering drugs used for executions? What about nurses who object even to providing care to women after they have had abortions? Do all claims of burden, backed by penalties, give rise to strict scrutiny under RFRA?

The question of whether religious liberty confers a right to discriminate is not new. Restaurants and schools have claimed rights to resist integration in the name of religion, and schools have argued a right to pay women less than men for reasons of faith. The courts have properly rejected such claims. Religious liberty has not been understood to mean the right to impose harm on others. The question for Judge Gorsuch is whether he will respect this precedent.