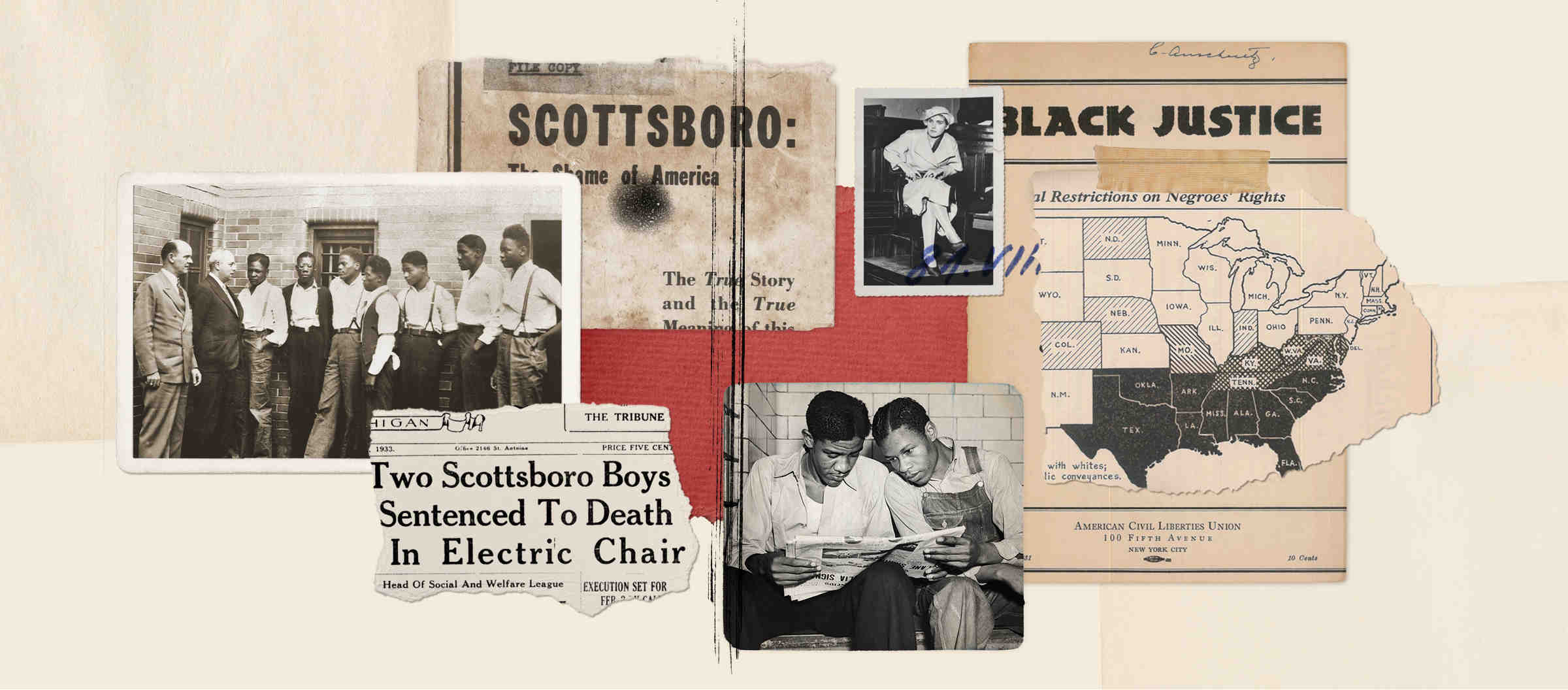

The Saga of The Scottsboro Boys

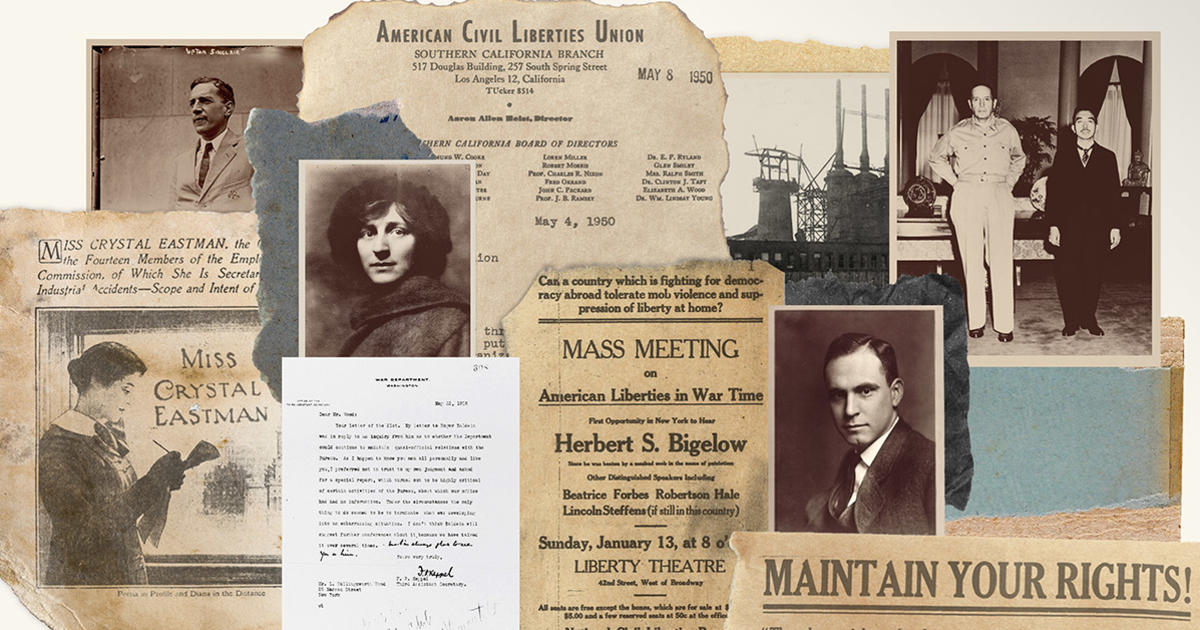

In 1931, the ACLU released its “Black Justice” report. The slender pamphlet explored the contradiction between the promises of the American Constitution and the “galling limitations put upon” Black Americans. It criticized laws and policies barring Black people from enjoying a decent education, a fair wage, trial by their peers, the right to vote, and the right to marry outside the race.

Astonishingly blunt for the era, the report was a clear reflection of then-ACLU Executive Director Roger Baldwin’s intent to expand the ACLU’s agenda — as was the ACLU’s deep involvement in one of the most explosive legal dramas of the day, which bluntly illustrated the grave mistreatment of Black Americans by the criminal justice system — and particularly the Jim Crow system of the South.

That drama revolved around nine Black youths charged with raping two white girls on a freight train in Alabama. The youths became known as the Scottsboro Boys, and the case became a window into the South’s unremittingly brutal system of justice.

As Baltimore Afro-American newspaper correspondent Paul Peters summed it up in 1932: “At first the South looked upon Scottsboro as just another ‘Negro rape’ case … They called the boys ‘black fiends’ and ‘Negro brutes’ and clamored for ‘quick justice’ — meaning wholesale slaughter.”

But as the world focused “upon that one little self-satisfied town in Alabama,” people “began to read the court records, to gather information, to ask embarrassing questions. ‘This isn’t a trial,’ they cried. ‘This is a lynching. This is murder!”’

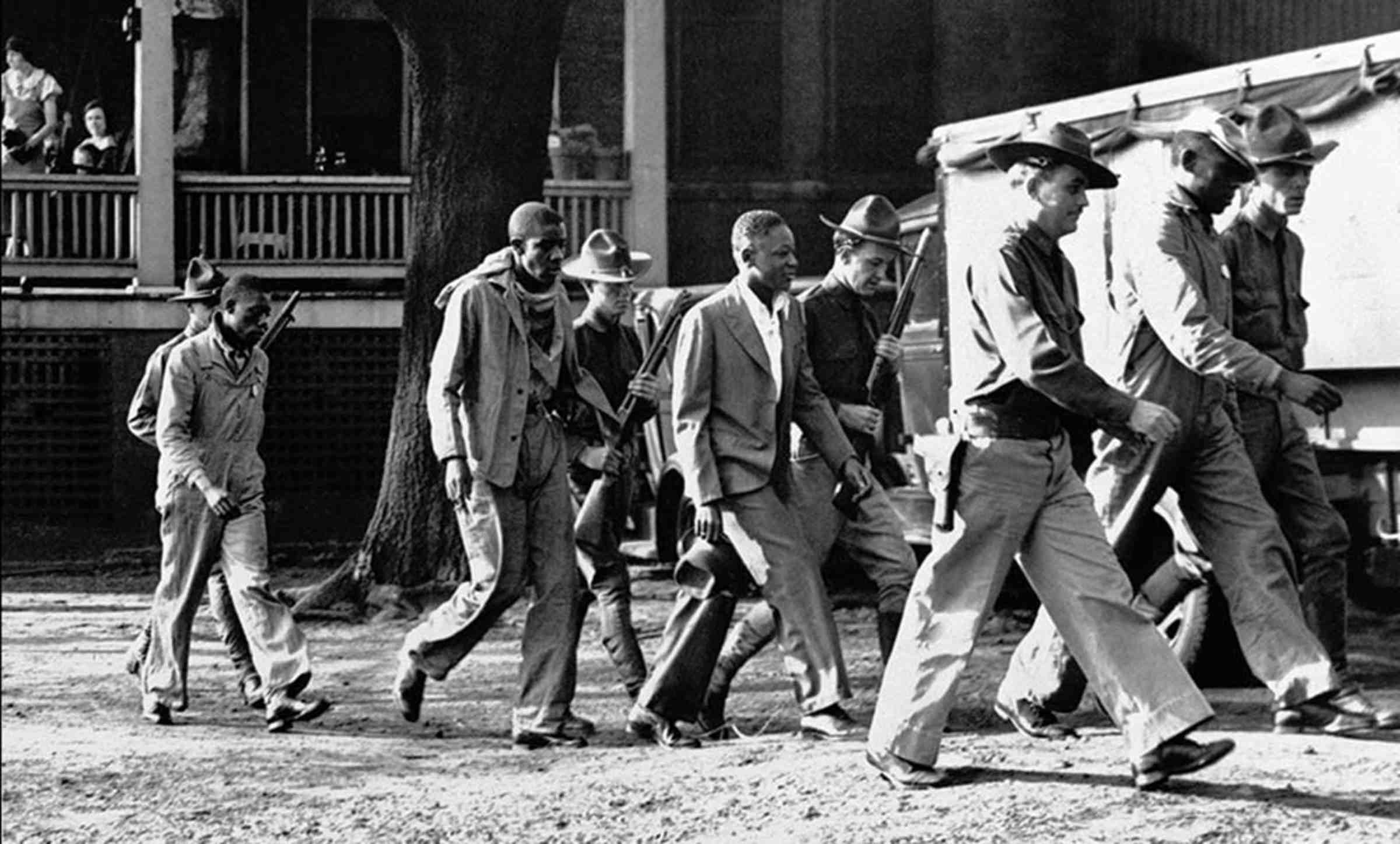

Ruby Bates and Victoria Price, at the time of arrest of the Scottsboro Boys in Scottsboro, in 1931.

Wikipedia

The case unfolded with astounding rapidity. It was less than a week from the arrest of the suspects on March 25, 1931, to the grand jury indictment, which took place on March 30. The trial was set for April 6.

The indictment rested on the testimony of the two alleged victims. They claimed that the nine Black youths came upon them and several white male companions in a freight car, whereupon the young Black men ejected the white boys and raped the young women.

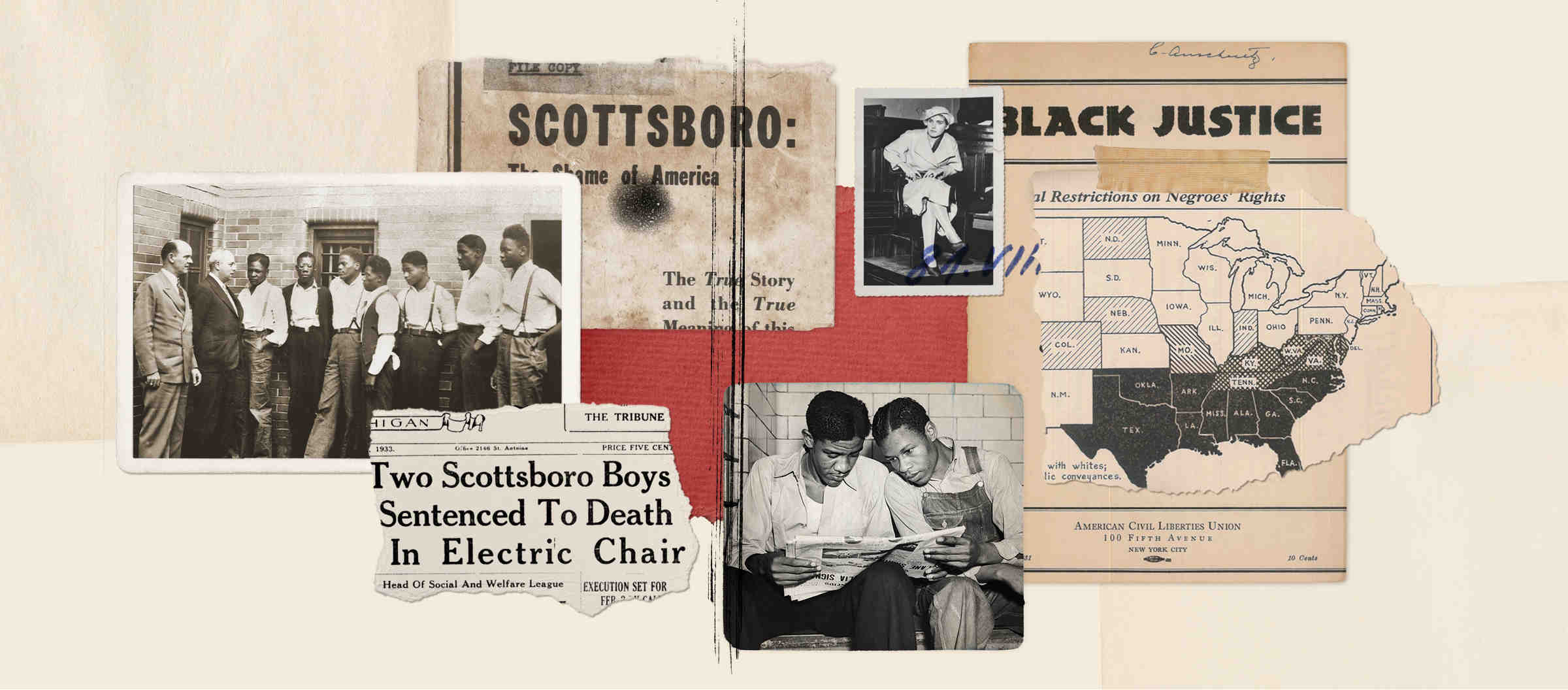

The suspects were taken to the jail in Scottsboro but had to be removed, under the protection of 100 national guardsmen, when a mob threatened to lynch them. They were held some 60 miles away and delivered to Scottsboro the morning of April 6 for their trials.

In this April 6, 1933 file photo, four of the Scottsboro Boys prisoners are escorted by heavily-armed guards into the courtroom.

AP Photo/File

Some 10,000 visitors crowded into tiny Scottsboro — whose normal population was 2,000 — on the first day of the trials, which proceeded at a lightning pace. The first two convictions — of Charlie Weems and Clarence Norris — came on April 7, the second day of trial. Two days later, eight of the nine stood convicted and sentenced to death, with their executions scheduled for July 10. Jurors had deadlocked on the fate of the ninth defendant, 14-year-old Roy Wright. Seven jurors were holding out for the death penalty, although prosecutors, because of his age, had only requested a life sentence.

Immediately following the trials, George Mauer of the International Labor Defense (a communist-linked legal defense organization) sent a telegram to Alabama Gov. Benjamin M. Miller saying that the young men had been framed and were victims of a “legal lynching.” Mauer demanded a stay of execution, promising to file a motion for a new trial or appeal.

The ACLU was not initially involved. But as the case attracted increasing attention, the ACLU dispatched Hollace Ransdell, a young Columbia-educated journalist, to take a closer look.

Ransdell produced a detailed and nuanced report. It challenged the tale of the two white “mill girls” from Huntsville, Alabama — Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, 21 and 17, respectively — who had dressed up in overalls and “hoboed their way by freight train” to Chattanooga, Tennessee supposedly to seek work.

According to Price, she and Bates spent the night in Chattanooga with a friendly woman (whom investigators could not locate). Unable to find jobs at various mills (which they never specifically identified), the girls decided to return home the next morning. They boarded an oil tanker and later climbed into an open freight car where they met seven friendly white boys, whom Price said she joined in laughter and song. When the two girls were roughly halfway home, testified Price, 12 Black boys, one waving a pistol, invaded the car and forced all but one of the white boys to leap from the fast-moving train.

In this April 7, 1933 photo, Ruby Bates sits in the witness stand in a courtroom in Decatur, Alabama. Saying that Dr. Harry Emerson Fosdick had urged her to tell the truth, Bates denied that the nine black teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Boys, had assaulted her and her companion.

AP Photo

She claimed six of the Black youths raped her and six raped her companion. Three of the alleged assailants left the train. Meanwhile, the white boys, who supposedly had been forced from the train, notified the station master. The nine young Black men who remained on the train were seized by an armed posse at Paint Rock, a town roughly 20 miles outside of Scottsboro. Neither girl showed evidence of rough treatment, although they did show signs of sexual intercourse, testified a doctor at the trial.

George Chamlee, an attorney for the ILD, told Ransdell that Price and Bates originally said nothing about rape; that those allegations were only made after the girls had assessed “the spirit of the armed men that came to meet the train and catch the Negroes.”

Ransdell’s conversations with the two girls convinced her that Chamlee was right. Victoria Price, she concluded “was the type who welcomes attention and publicity at any price.” She also had “no notions of shame connected with sexual intercourse in any form and was quite unbothered in alleging that she went through such an experience as the charges against the nine Negro lads imply.”

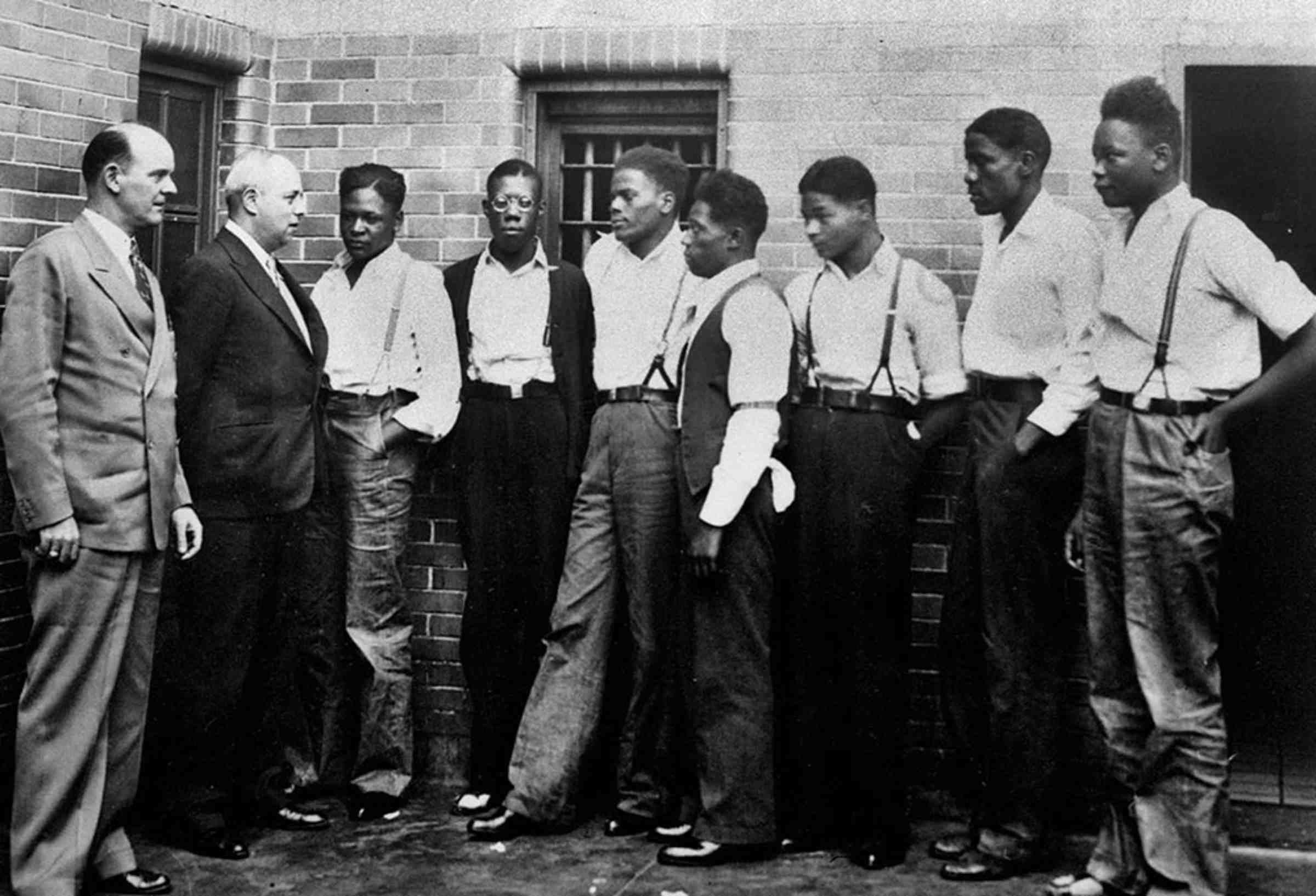

In this May 1, 1935 file photo, attorney Samuel Leibowitz from New York, second left, meets with seven of the Scottsboro defendants at the jail in Scottsboro, Ala. just after he asked the governor to pardon the nine youths held in the case. From left are Deputy Sheriff Charles McComb, Leibowitz, and defendants, Roy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Ozie Powell, Willie Robertson, Eugene Williams, Charlie Weems, and Andy Wright. The black youths were charged with an attack on two white women on March 25, 1931.

AP Photo

“Having been in direct contact from the cradle with the institution of prostitution as a side-line necessary to make the meager wages of a mill worker pay the rent and buy the groceries,” Ransdell’s report continued, “she has not a feeling of revulsion against promiscuous sexual intercourse ... It is very much a matter of the ordinary routine of life to her, known in both Huntsville and Chattanooga a prostitute herself.”

Price lived in a small, unpainted shack in Huntsville with her elderly mother, who was in poor health, “for whom she insistently professes such flamboyant devotion, that one immediately distrusts her sincerity” reported Ransdell. Although Price’s age “was variously reported in Scottsboro as 19, 20, and 21,” her mother “gave it as 24, and neighbors and social workers said she was 27.”

She also had “a reputation.” The chief deputy in Huntsville told a social worker that he left her alone because she was a “quiet prostitute, and didn’t go rarin’ around cuttin’ up in public and walkin’ the streets solicitin,’ but just took men quiet-like.” The sheriff thought she might be “running a speakeasy on the side with a married man named Teller.” He had not yet succeeded in catching the couple with liquor on them.

Ransdell also visited Bates, whom she described as a “large, fresh, good-looking girl, shy, but a fluent enough talker when encouraged … When I talked with her alone she showed resentment against the position into which Victoria had forced her, but did not seem to know what to do except to keep silent and let Victoria do the talking,” concluded Ransdell.

Like Price, Bates lived with her mother. “They are the only white family in the block. Of the five children in the family, two are married and three are living at home.” As Ransdell and Bates talked out front, the younger children in the household played with their Black neighbors.

Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP

Library of Congress

Ransdell also wrote about the conflict between the ILD and the NAACP. Both organizations had sent representatives to Scottsboro. Both had engaged lawyers.

“The two organizations differ so fundamentally on principles and tactics,” concluded Ransdell, “that any hope of a compromise in the legal control of the case seems impossible.” The ILD believed in mass demonstrations, bombastic propaganda, and other forms of public pressure. The NAACP believed in quietly working through the system: “They are most anxious to try to avoid antagonizing Southern prejudice.”

Ransdell reported that the NAACP’s Walter White had gotten four of the defendants to agree to NAACP representation and warned the defendants’ parents “that it meant electrocution for their sons to have anything to do with the ILD.”

Ransdell concluded that Alabama officials, including the trial judge, “all wanted the Negroes killed as quickly as possible in a way that would not bring disrepute upon the town. They therefore preferred a sentence of death by a judge to a sentence of death by a mob, but they desired the same result.”

Criminal defense lawyer Clarence Darrow is seen outside the White House in Washington, D.C., in this 1927 photo.

AP Photo

The ACLU’s direct involvement was complicated by its long history with the NAACP and the ILD. In the September following the boys’ convictions, the NAACP signed up the ACLU’s Arthur Hays and Clarence Darrow as volunteer counsel. Shortly after arriving in Alabama, the famous lawyers received a telegram from the ILD urging them not to “make trouble” and asking them to assist the ILD instead of the NAACP.

Hays and Darrow instead offered to work on the case without formally affiliating themselves with either organization. The ILD balked, and Darrow and Hays withdrew, as did the NAACP (which eventually found its way back to the case).

The bickering, however, continued. In a March 1932 article in The Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine, Darrow praised the NAACP and slammed the ILD for “seeking credit” in the case.

Meanwhile, a letter surfaced from Bates to a lover admitting the Black youths had not attacked the women. The ILD lawyers asked the Alabama Supreme Court to overturn the verdicts on several grounds: that the defendants had neither been provided with adequate counsel nor received due process, that the fear and hysteria enveloping the case had made a fair trial impossible, and that Eugene Williams, a juvenile, should not have been tried as an adult.

The state Supreme Court upheld all the convictions except Williams’s, who was granted a new trial. The others were to be executed that May. The NAACP offered to reenter the case.

Rejecting the NAACP’s help, the ILD engaged Walter Pollak, a highly respected lawyer who had represented the ACLU before the U.S. Supreme Court.

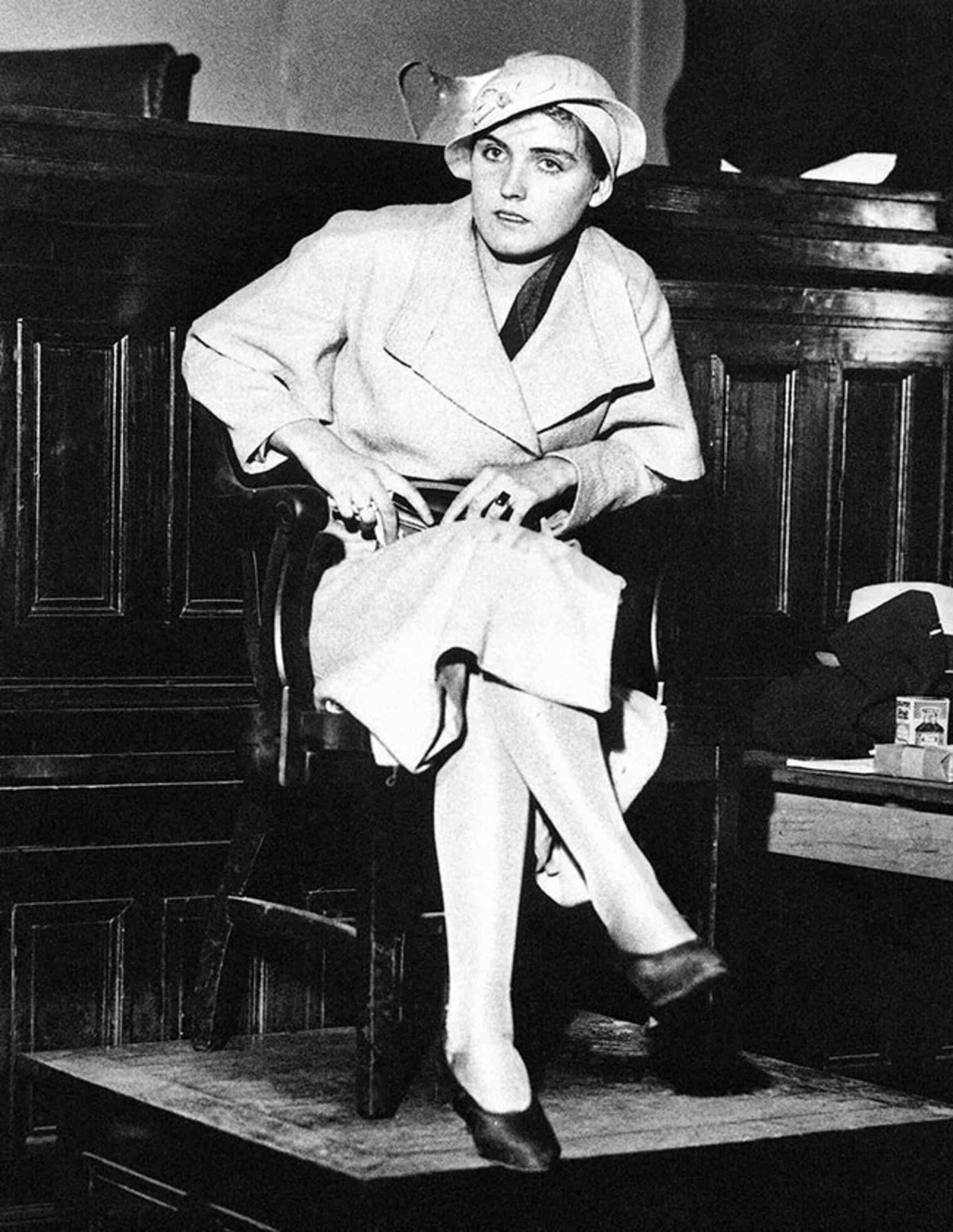

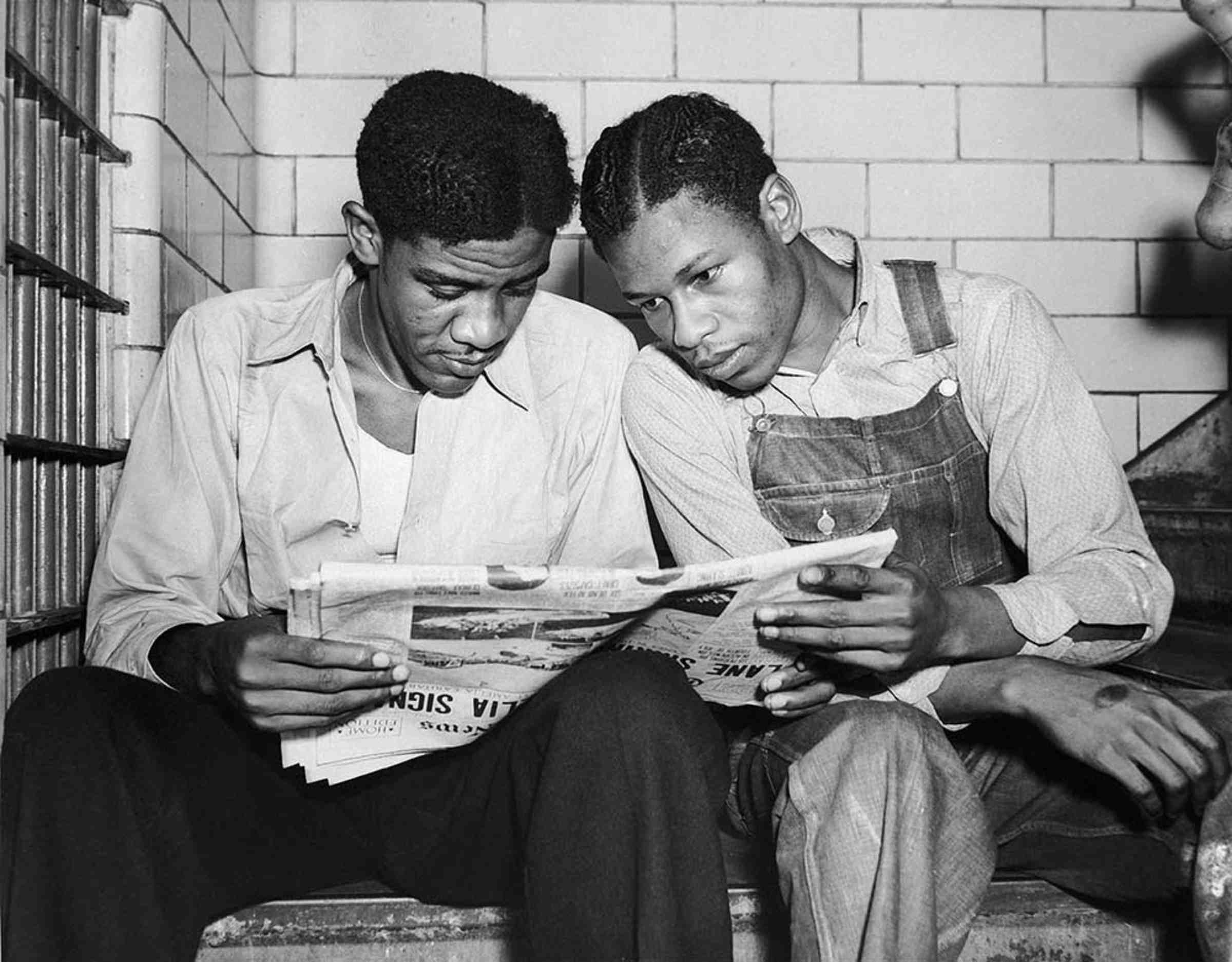

In this July 16, 1937 file photo, Charlie Weems, left, and Clarence Norris, Scottsboro case defendants, read a newspaper in their Decatur, Ala. jail after Norris was found guilty for a third time by a jury which specified the death penalty.

AP Photo

Pollak made several points to the Supreme Court: that his clients had not received a fair trial; that they had been denied the right to counsel and an opportunity to prepare a defense; and that (because Black people were systematically excluded) they had not been tried by a jury of their peers. On November 7, the Supreme Court sided with Pollak in Powell v. Alabama.

Writing for the majority, Justice George Sutherland pointed out that the boys had been denied the right to hire their own counsel. “That it would not have been an idle ceremony ... is demonstrated by the fact that, very soon after conviction, able counsel appeared in their behalf,” added Sutherland.

Baldwin hoped that decision would end the boys’ ordeal, that Alabama would drop the case. But that was not to be.

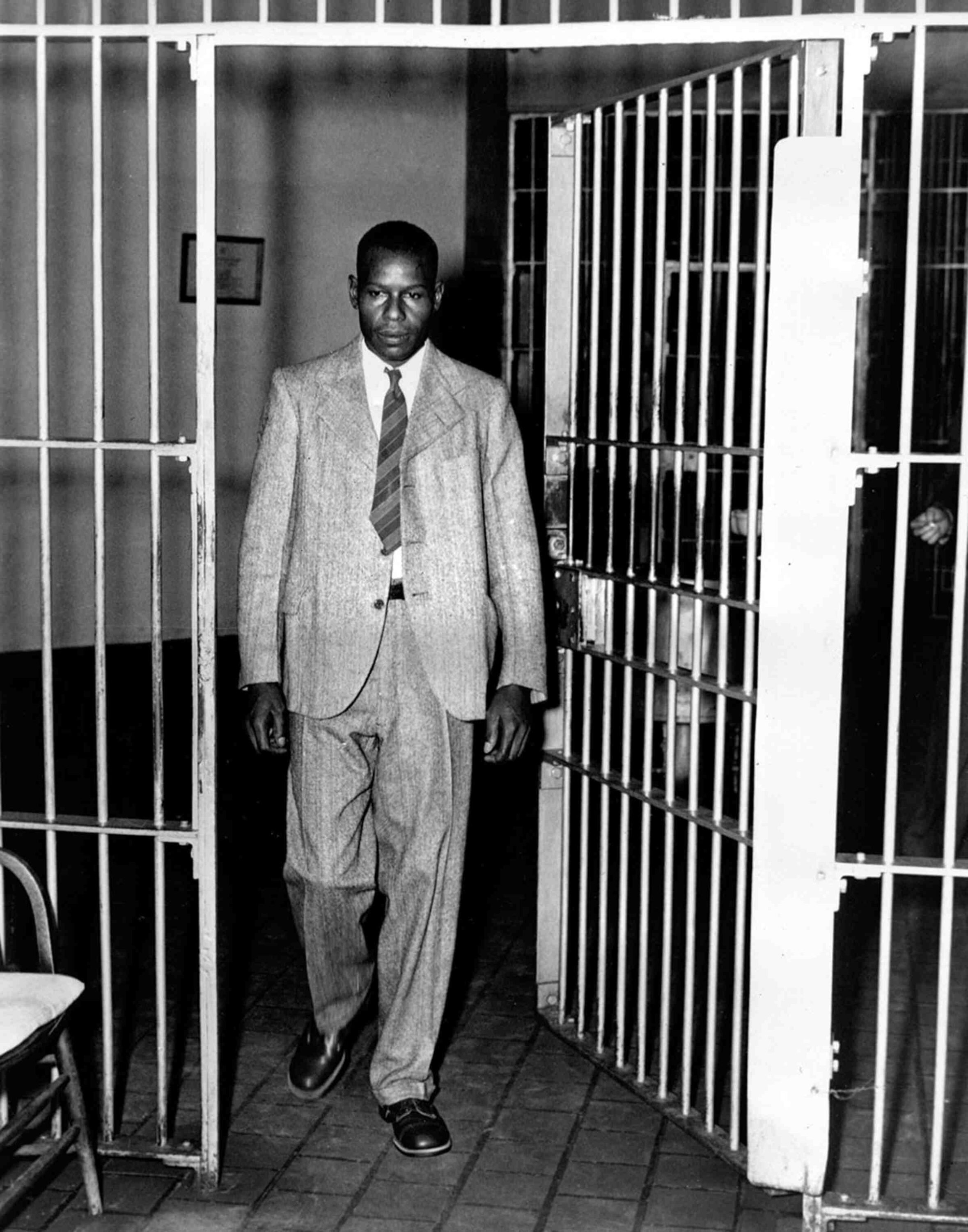

Clarence Norris, one of nine Black men involved in the Scottsboro case of 15 years, walks through the main cell gate at Kilby Prison in Montgomery, Ala., Sept. 27, 1946, after receiving his parole after serving nine years of a life sentence.

AP Photo

Outraged by the Supreme Court’s interference, Alabama again put the boys on trial. In April 1933, Haywood Patterson, the first of the Scottsboro defendants to be retried, was again found guilty.

The surprise came in July. In what the Norfolk Journal and Guide called “a decision momentous in a Southern court,” Judge James E. Horton set aside the jury verdict.

Horton tore apart Price’s testimony. She had claimed that the wounds from the assault left her lacerated and bleeding, with a gash on her head and her clothes saturated with semen and blood. Yet neither of the doctors who treated her saw a head wound and no blood or semen was found on her clothes. Nor were the women overwrought when discovered, as would have been expected, Horton’s decision noted. And the white boy put on the stand “contradicted her.”

Horton doubted Black boys would have chosen such an exposed place to rape white women. He also noted the women had previously attempted to bring charges against Black people, by “falsely accus[ing] two negroes of insulting them,” and that their testimony was “contradicted by other evidence.”

Patterson’s third trial was before Judge William Washington Callahan, who blithely assured prospective jurors that “belief in the Negro’s inferiority does not disqualify you for jury service.” Patterson again was found guilty. Days later, Clarence Norris was also found guilty and, like Patterson, sentenced by Callahan for execution.

In June 1934, Judge Horton lost his bid for re-election, which was attributed to his favorable ruling for the Scottsboro Boys.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

On April Fools’ Day, 1935, the Supreme Court again weighed in on the Scottsboro cases (Patterson v. Alabama and Norris v. Alabama). Because of the country’s “long-continued, unvarying, and wholesale exclusion of negroes from jury service,” wrote Chief Justice Charles Hughes, “the judgment must be reversed.”

It was another landmark decision for the Scottsboro Boys, but it brought neither vindication nor freedom. They had simply won the right to be retried.

Meanwhile, the bickering defense organizations worked out a rapprochement. In December 1935, on the eve of yet another set of trials for the Scottsboro youths, the ACLU, NAACP, ILD, League for Industrial Democracy, and the Methodist Federation for Social Service came together as the Scottsboro Defense Committee. The first retrial, under Judge Callahan, was set for January 1936.

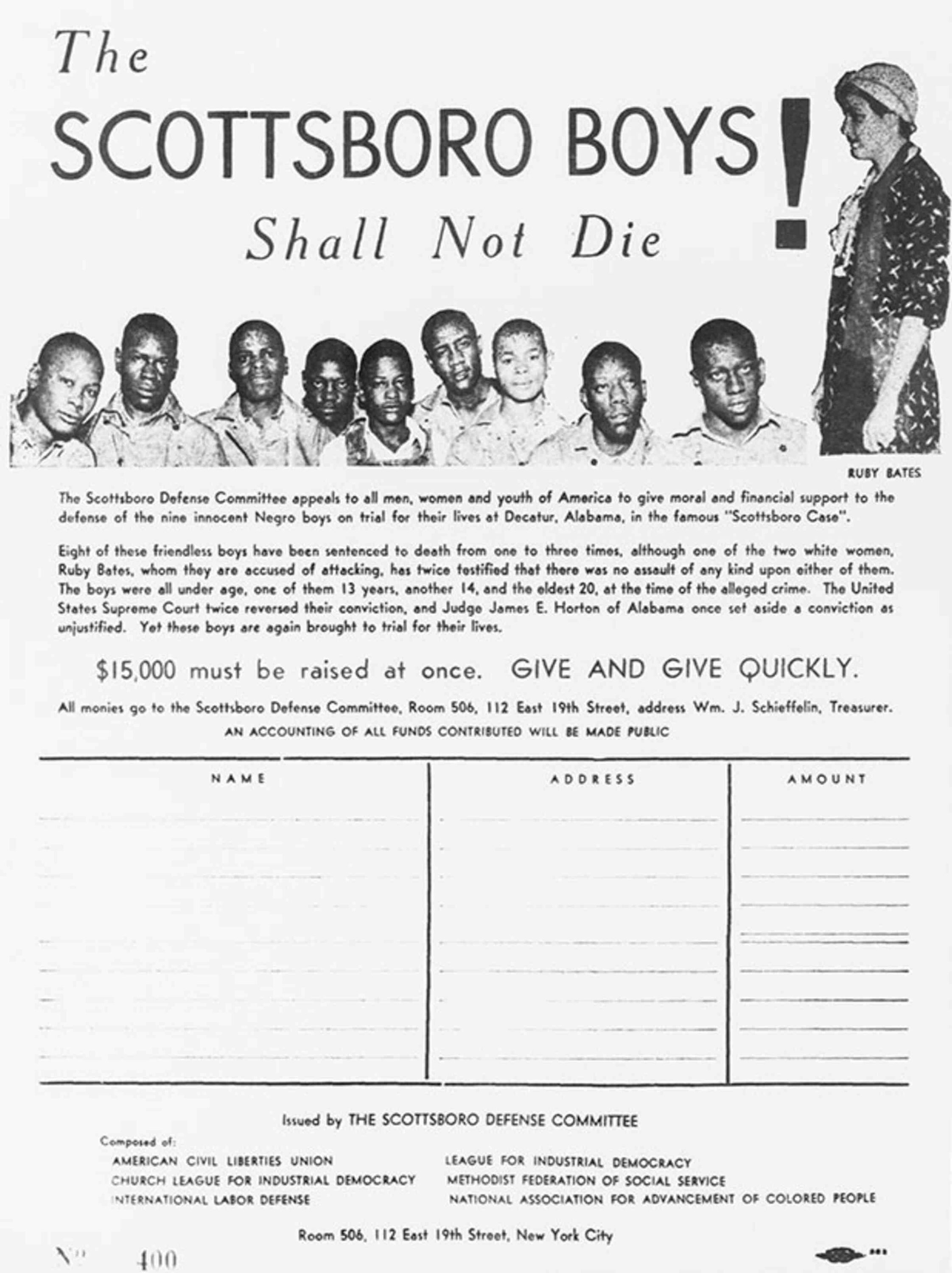

Fundraising letter from the Scottsboro Defense Committee

ACLU Archives

This time, twelve Black people were included in the jury pool of 100. All were challenged by the state and removed. The trials again took place before all-white juries. Again, the boys were found guilty.

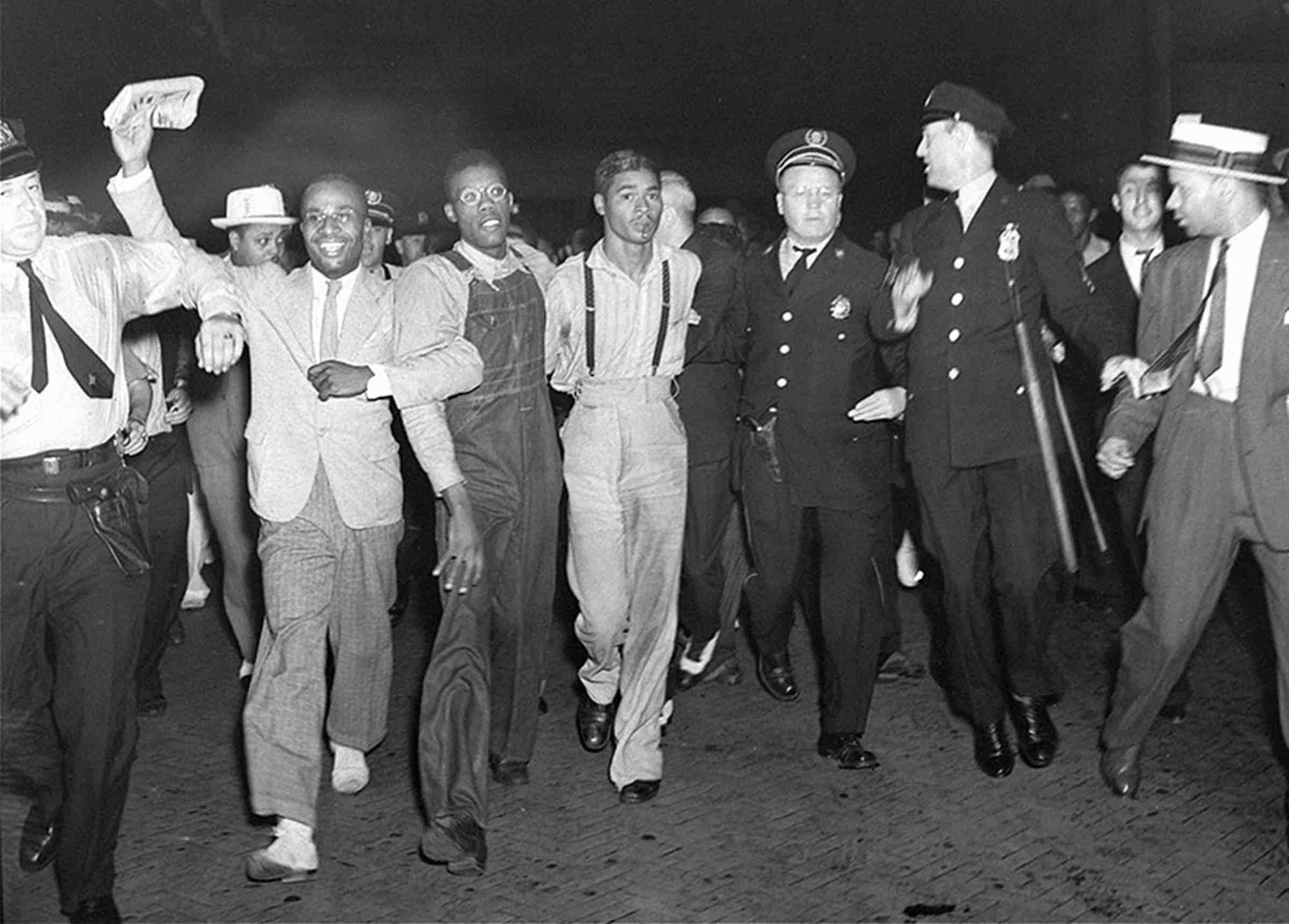

Over the next several years, the Defense Committee repeatedly went to court, launched public campaigns, and sought pardons for their clients. In July 1937, they finally got a break. On July 24, 1937, Alabama released four of the original nine defendants: Olen Montgomery, Roy Wright, Willie Roberson, and Eugene Williams. In a prepared statement, the prosecutor pronounced Roberson and Montgomery innocent. Williams and Wright were shown clemency, he explained, because they were juveniles at the time of the alleged crime. The state also pronounced Ozie Powell innocent, but he remained in prison — under a 20-year sentence — for attacking a guard.

In this July 26, 1937 file photo, police escort two of the five recently freed "Scottsboro Boys," Olen Montgomery, wearing glasses, third left, and Eugene Williams, wearing suspenders, forth left through the crowd greeting them upon their arrival at Penn Station in New York.

AP Photo/File

The Defense Committee appealed to Gov. Bibb Graves to free their clients who remained in prison, arguing that some could not be innocent and the rest guilty. Committee members negotiated an agreement with the governor to pardon the remaining four in October 1938, but the governor reneged.

On October 25, 1976, Alabama Gov. George Wallace pardoned Clarence Norris at the request of the NAACP. Norris, then 64, had spent 15 years behind bars, five of those on death row. At an event that December, Norris was asked how he would change things if he could relive his life. “I would not come back to this life at all,” he replied.

At the time of Norris’s pardon, Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems, and Andy Wright were presumed dead and therefore ineligible for pardons. In 2013, after the legislature passed a law permitting posthumous pardons, they received full and unconditional pardons.

Copyright © 2020 by Ellis Cose. This excerpt originally appeared in Democracy, If We Can Keep It by Ellis Cose. The book was published by The New Press in July and is . Reprinted here with permission.

Ellis Cose is the author of a dozen books on issues of national and international concern, including the best-selling “The Rage of a Privileged Class” and “The Best Defense,” a novel. For 17 years, Cose was a columnist and contributing editor for Newsweek magazine. He is the former editorial page chief of the New York Daily News as well as an independent radio documentary host and producer. Cose was the inaugural writer in residence for the ACLU.