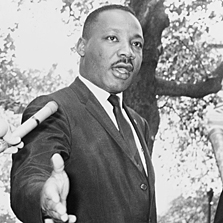

Today voters are going to the polls in South Carolina to exercise their most fundamental democratic right: the right to vote. This week we celebrated the life and work of Martin Luther King, and in doing so we recall his championing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Recognizing the pitifully low number of blacks who were eligible to vote at that time, Dr. King believed that until all African Americans were able to participate in the electoral process, there could be no real justice in this country.

Forty-seven years later, we are seeing the resurgence of efforts to enact laws that will have the effect of reducing the number of black people participating in the election. So instead of moving closer to the all-inclusive democracy King dreamed of, we are seeing steps which are calculated to fragment the nation along racial lines. We see this in the thinly veiled, coded references designed to gain support by appealing to uglier, racial feelings. In a sense, the discussions surrounding the South Carolina primaries may be a portent of the coming campaign and the likelihood that King’s dream of a unified country may ever be achieved. Trying to gain political advantage by balkanizing the country may yield short term victories but bodes ill for the country as a whole.

The fact that Martin Luther King seems like an increasingly distant historical figure is only partly explained by the relentless passing of time. The rest can be explained by the limited way in which his life and work is often described. King is most frequently linked with his protests against segregated buses and lunch counters and other examples of apartheid that seem far removed from the present era, a time when an African American occupies the nation’s highest office.

Any complacency about society’s success in addressing the most obvious forms of discrimination is unwarranted. In fact, significant parts of King’s dream remain unrealized and seldom commented upon. Throughout his struggle, King emphasized economic inequalities in American society. In his “I Have a Dream Speech” he railed about the fact that, a hundred years after emancipation, African Americans still lived “on a lonely island of poverty.” He complained that the passage of a century did not change the fact African Americans “still languished in the corners of American Society.” On the day he died, he was protesting the mistreatment of Memphis sanitation workers, a mistreatment that was in part economic.

What would the Martin Luther King who was concerned with the economic justice make of the fact that, in a period of general economic crisis, African Americans are hit twice as hard, enduring an unemployment rate twice that of the nation as a whole? How would he regard the , a disparity far worse than when he was living? What would he think of the explosive growth in the number of black men incarcerated since his time? How would the man who said “we cannot be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their self-hood and robbed of their dignity” view the draconian and unfair policies which push black children out of schools and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems?

Most topically, what would the man who dreamed of African-American inclusion in the political and social life of the country make of ? At a time when race still figures prominently in American life, discussion about it is either suppressed or used as a tool of fear to manipulate voter emotion. Now that economic issues have eclipsed the fear of rising crime, the spectre of Willie Horton has given way to the image of the lazy black person living off unemployment. No doubt he would share the view that talking about black people living off of other people’s money or suggesting that poor black children need to learn the “habit of work” is a calculating and cynical view given the unavailability of employment opportunities for poor black adults and the harsh realities faced by those who can find jobs but who need to work multiple jobs to scrape by.

If King were alive today, he would be continuing the struggle for racial justice and we must too. In the end, we honor him most not by celebrating his achievements but by fighting to achieve the unrealized parts of his dream.

Learn more about racial justice: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .