As Obama’s Presidency Comes to an End, Take Some Time to Reflect but Never Forget to Keep Climbing

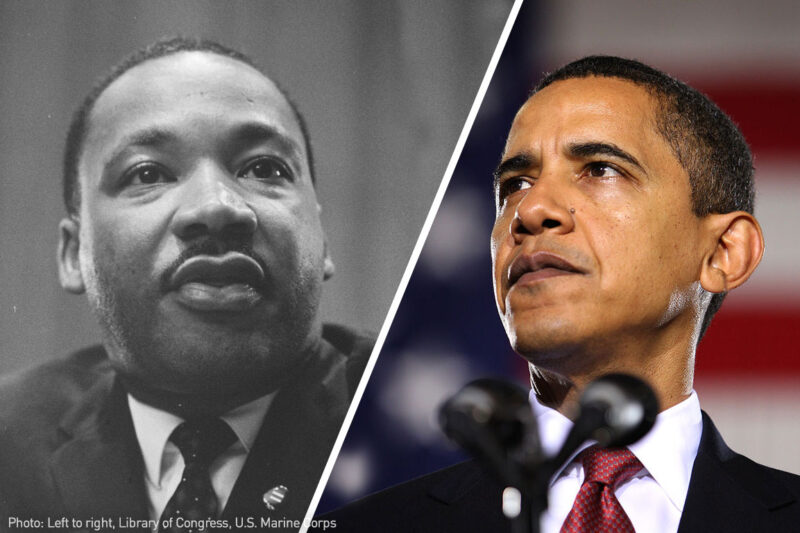

The coincidence of the end of the Obama administration and the celebration of the life of Dr. Martin Luther King invites some reflection on the connection between the election of the first Black president and the life and work of the great civil rights advocate. As always, I tend to view questions of national importance through the filter of my family and the way that it is affected by broader issues.

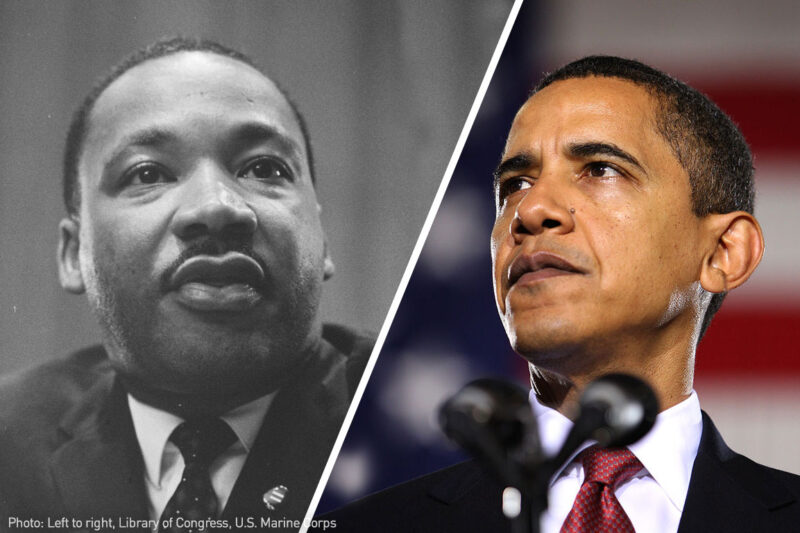

When thinking of President Obama’s presidency, I invariably return to thoughts of the night in 2008 when he was elected. I spent the early part of the evening watching the returns with my now 97-year-old mother. My mother was born in Summerville, South Carolina, and came up to New York at age 9 in 1928 to rejoin her mother, who had moved north to work as a domestic for white families in Pennsylvania and New York. Like so many black families who were part of the great migration, they had moved north to escape discrimination and the lack of opportunity in the South only to face different manifestations of America’s original sin in the North.

Her lifetime of facing discrimination great and small had taken a toll on my mother. Despite the ongoing positive results, she insisted that Obama could not win, not given this country’s racial history. So deep was this conviction that when I called her the following day to hear her reaction, she seemed audibly disoriented, as if her world had suddenly turned upside down.

Eight years later, her granddaughter — my daughter Zoe — would be teaching a class of second-grade students in Brooklyn, all of them students of color, who had never known anything but a Black president. The students, however, did not take the racial similarities between themselves and the first family for granted. Zoe shared with me her students’ writings, which reflect pride and identification with this charismatic leader and his family. That difference between a senior citizen whose history would not permit her to imagine that a Black person could be elected president and a group of young people for whom a black president was their only reality reflects something about Martin Luther King’s dream.

Perhaps reflecting a national tendency to downplay the history of race and its continuing existence in the United States, some people chose to regard Obama’s election as a sign we were on the verge of a race-blind society. Reality, as it has a way of doing, intervened. The persistence of massive disparities in wealth, in levels of incarceration, in employment, in access to education and housing, and in reports of shooting of unarmed people of color — not to mention the massive racial and economic fissures revealed by the most recent presidential election — made it impossible for anyone except the most delusional to sustain the idea of having removed race entirely from the factors affecting opportunity in this country.

And Obama’s election did not fully realize the hopes that so many had. My organization, the ACLU, fought back against many of the policies of the Obama administration, including his record level of deportations and his unaccountable use of drones. But in many important ways, Obama’s election represented substantial, significant progress toward the realization of Martin Luther King’s dream.

Some critics, myself included, faulted the president early on for a seeming reluctance to take on adequately the continuing presence of racial discrimination. But when he did — in a number of instances, including his personal and heartfelt reaction to the shooting of Trayvon Martin — he did so in a way that was moving and incisive and that showed a clear willingness to swim against the overwhelming current of opinion that favors sweeping away the historical and current realities of discrimination. Here, for the first time, was a president who understood and could express the pain and frustration of Black parents. People who could not understand why so many of their fellow citizens seemed to attach so little value to the lives of their children.

And Obama’s recognition of racial realities were carried out through the actions of agencies that dealt with police accountability, the unfair school disciplinary practices which pushed children of color out of the educational system into the criminal justice system, and the use of the criminal justice system as a way penalize poor communities in order to balance municipal budgets. These concerns, both about the need to value the lives of people of color and the economic unfairness which denied too many Americans of opportunity, were ones which King repeatedly espoused, particularly toward the end of his life.

But Obama’s significance cannot be assessed solely by his policies. Perhaps the most important part of his legacy was the example that he and his family set not only for my daughter’s second-grade students but the country as a whole. Here was a president who was Black and intelligent, empathetic, well-spoken, thoughtful, reasonable, and cool. My god was he cool. None of these qualities could completely shield him or his intelligent, elegant, and committed wife from base and demeaning comments from perhaps unredeemably racist people. But for much of the country, if not the world, he represented the very best of America.

The end of his administration raises questions about both Obama’s legacy and the resiliency of Martin Luther King’s dream. None of the adjectives listed above spring to mind when considering Obama’s successor. And some of the same students who my daughter has taught who so identified with the president approached her the day after the election to ask whether their families would be separated when their parents were deported back to their native countries in the Caribbean, a question no 7-year-old should ever have to deal with.

The fragility of the advances marked by the election of a Black president and the progress, incomplete as it was, in addressing discrimination made over the last few years is underscored in a time when so many of the advances in the area of civil rights seem particularly vulnerable as a result of the change in administration. But that vulnerability would not have been news to MLK. He recognized that the struggle for equality would be a protracted one whose goals would not be achieved by the passage of legislation, or a court decision, or even the election of a Black president.

Like the mother in the Langston Hughes poem, King recognized that life “ain’t been no crystal stair.” But he knew, like I believe Obama knows and my daughter's students will learn, that we can’t turn back or sit down. We must instead keep climbing.