While I celebrate our accomplishments and the profound struggles of those who paved the way for me — including Dred Scott — the battle is not yet over.

During Black History Month and throughout the year, we reflect on the achievements of Blacks in this country and the difficulties over which we have triumphed in our ongoing fight for equal rights and justice. As I consider our distinguished history, and the depths from which we've come, I am grateful to have the opportunity to work with colleagues at the ACLU, who have dedicated their lives to protecting the rights of all, regardless of race, class, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or political affiliation.

A poignant moment for me in Black history was the . In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sanford, by a margin of 7 to 2, that Black people, whether free or enslaved, were "beings of an inferior order and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations." Indeed, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney famously insisted that Blacks are "so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." But the Court went even further, warning that a ruling in Mr. Scott's favor would lead to unthinkable results — namely that the "negro race" would gain "the right to enter every other State whenever they pleased, ...to sojourn there as long as they pleased, to go where they pleased ...the full liberty of speech in public and in private upon all subjects upon which its own citizens might speak; to hold public meetings upon political affairs, and to keep and carry arms wherever they went."

The Court's decision reflected the scourge of racism that so deeply infected American society at the time and, by many accounts, served to galvanize the abolitionist movement and accelerate this country's plunge into civil war four years later. While most now regard the Dred Scott Decision as an embarrassing taint on the Court's jurisprudence, it remains a frightening reminder of the depth of hatred and irrationality that once ruled the day. But Dred Scott and the legacy of slavery in this country, as well as the tremendous strides we have taken over the last 150 years, also point to what I believe to be a larger truth: it is much harder to hate and oppress a people when you recognize their humanity. (After all, it was Chief Justice Taney's belief in the inherent inferiority of people of African descent that allowed him to dismiss Mr. Scott's petition so brazenly and completely.) And not only does this recognition make hate more difficult to sustain, it also makes the denial of fairness, justice and common human decency that much harder to justify.

Notwithstanding the progress made since the Dred Scott case, one need only consider the devastating impact the criminal justice system has had on the Black community in recent decades, and the extent to which lawmakers and the public have been willing to compromise the rights of the poor and dispossessed whenever it is politically convenient, to realize that efforts to eviscerate the civil liberties of the most vulnerable members of our society have not yet disappeared. Indeed, the recent creation of the ACLU's Criminal Law Reform Project reflects a recognition of that sad reality. So while I celebrate our accomplishments and the profound struggles of those that paved the way for me — including Dred Scott — the battle is not yet over.

Jason Williamson is a staff attorney with the ACLU’s Criminal Law Reform Project, focusing on Fourth Amendment, police practices and indigent defense reform litigation. Jason began his legal career with the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, and later served as a defense attorney and founding member of Juvenile Regional Services in New Orleans. Jason received a B.A. from Harvard University and a J.D. from New York University School of Law.

This blog post is one of several personal testimonials written by ACLU staff members to commemorate Black History Month.

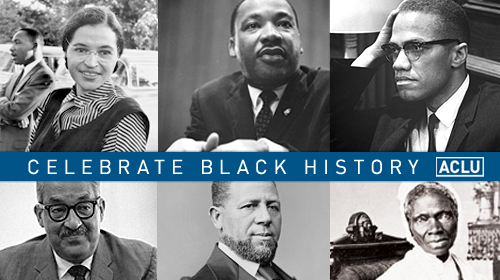

Do you know who’s pictured in our Celebrate Black History logo? Top row, from left to right: , and . Bottom row, from left to right: , and .

Learn more about racial justice: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .