Clearing the Record: How Eviction Sealing Laws Can Advance Housing Access for Women of Color

In 2008, Ashley called the police after her ex-partner refused to leave her apartment, threatened her, and threw a rock at her window. The police issued a “trespass notice,” prohibiting Ashley’s abuser from coming back to the home. When Ashley informed her landlord about the incident, the landlord responded by filing an eviction against Ashley and her child. Because evictions based on domestic violence are unlawful, the court threw out Ashley’s eviction. But seven years later, Ashley still to obtain housing because of the prior eviction filing on her record.

As Ashley’s story illustrates, tenants with prior eviction records are indefinitely of housing opportunities. Landlords routinely employ screening policies that deny housing to any renter previously named in an eviction case — regardless of whether the case was dismissed, occurred many years ago, or was filed on unlawful grounds. In doing so, landlords frequently rely on tenant-screening companies, who capitalize on to court records to develop .

As eviction screening policies deprive families of housing, they also perpetuate discrimination against people of color — and in particular, . Fighting the requires finding data-informed solutions that advance fair housing for all.

Eviction’s Fallout Across Race and Gender Lines

Eviction has emerged as a national crisis in the face of rising housing costs, stagnant wages, and minimal protections for tenants. An estimated are filed each year — at a rate of four evictions every minute. For many tenants, eviction can have a of devastating consequences, including , , , and even .

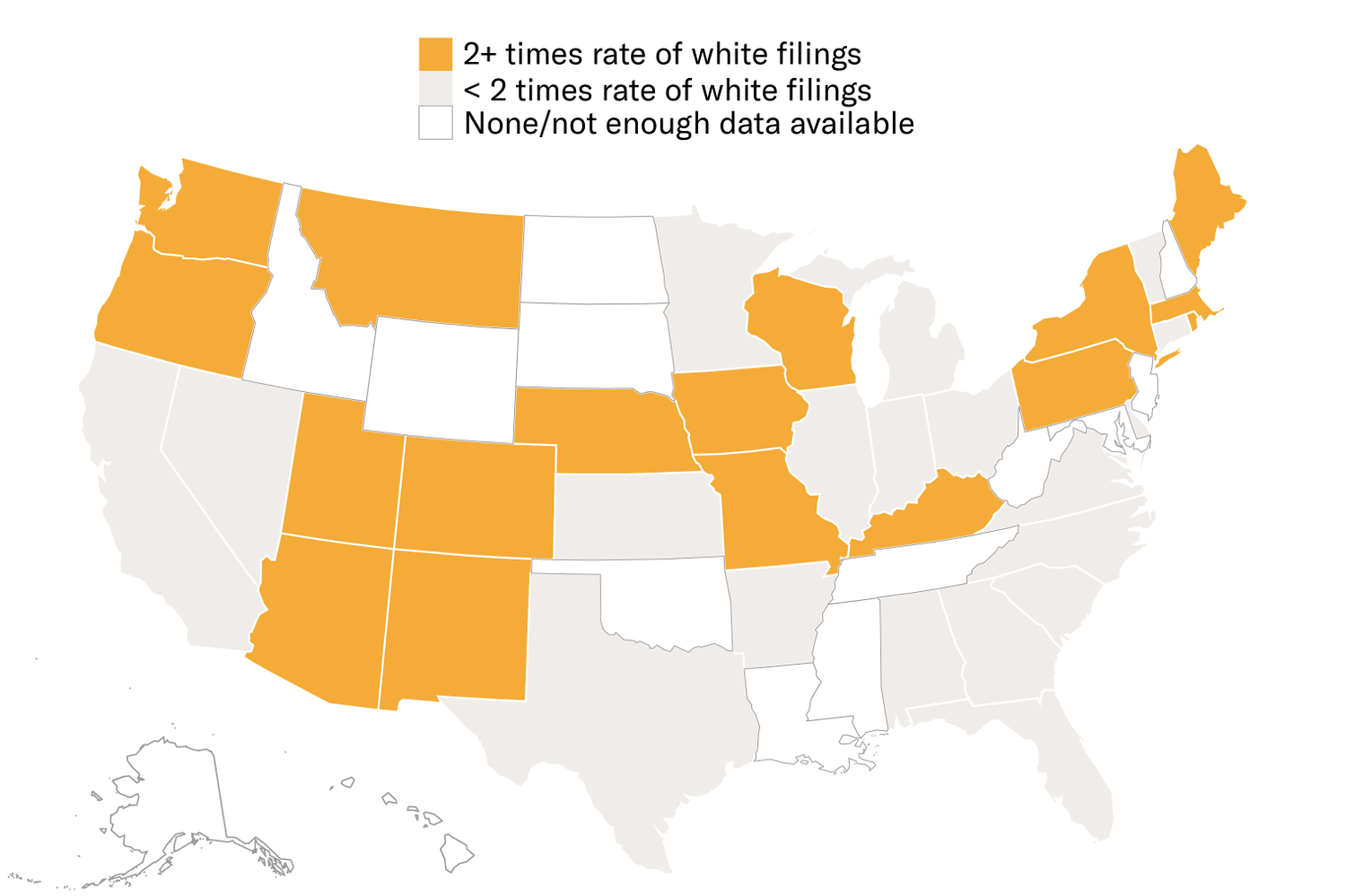

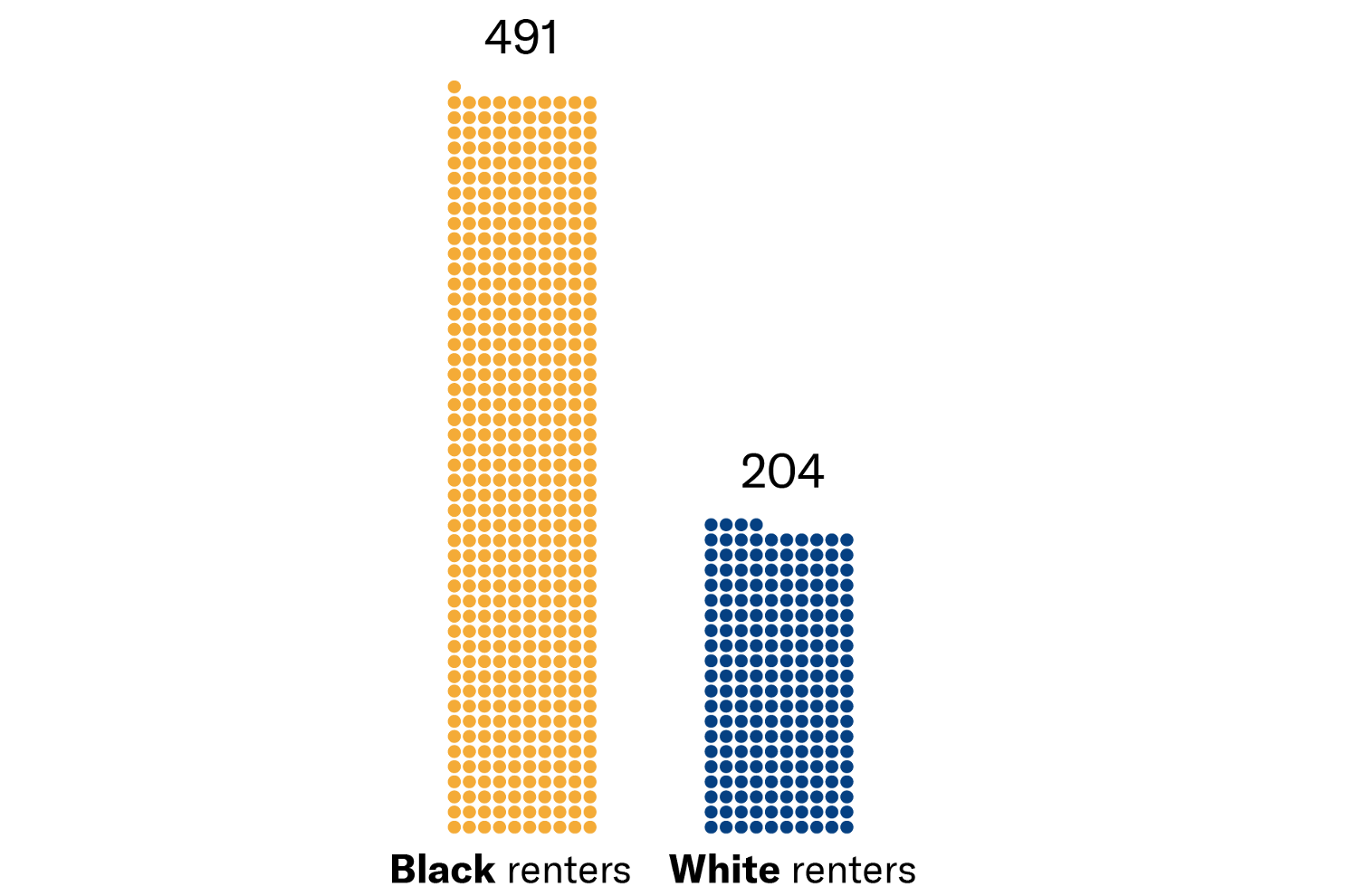

Importantly, eviction disproportionately burdens tenants of color and, in particular, Black women. The ACLU’s Data Analytics team analyzed national eviction data from 2012 to 2016, provided by the 1, and found that on average, Black renters had evictions filed against them by landlords at nearly twice the rate of white renters. Other across the country have consistently similar disparities, revealing that eviction and its lasting impact replicate and perpetuate existing .

Black female renters were filed against for eviction at double the rate of white renters or higher in 17 of 36 states

As Ashley experienced, the mere existence of a prior eviction filing is enough to lock tenants out of housing opportunities for years to come --- even when the case did not result in a final judgment against the tenant. The lasting stigma of a prior eviction filing often compels poor tenants to avoid court involvement at all costs. Rather than exercising their rights, many tenants endure horrible living conditions or comply with unlawful lease termination notices to avoid sustaining the permanent mark of an eviction filing.

Eviction in Massachusetts

These stark race and gender disparities in eviction are even more alarming at state and local levels. In Massachusetts3, where state legislators are working to advance legislation to eradicate this issue, Black renters are, on average, 2.4 times more likely to have an eviction filed against them than white renters, even though they make up only 11% of the renting adult population4.

Black renters in Massachusetts had evictions filed against them at 2.4x the rate of white renters

Per 10,000 renters

Data compiled by the Eviction Lab was available for 11 of 14 Massachusetts counties. Data span 2012 through 2016, but not all counties had all 5 years of data available.

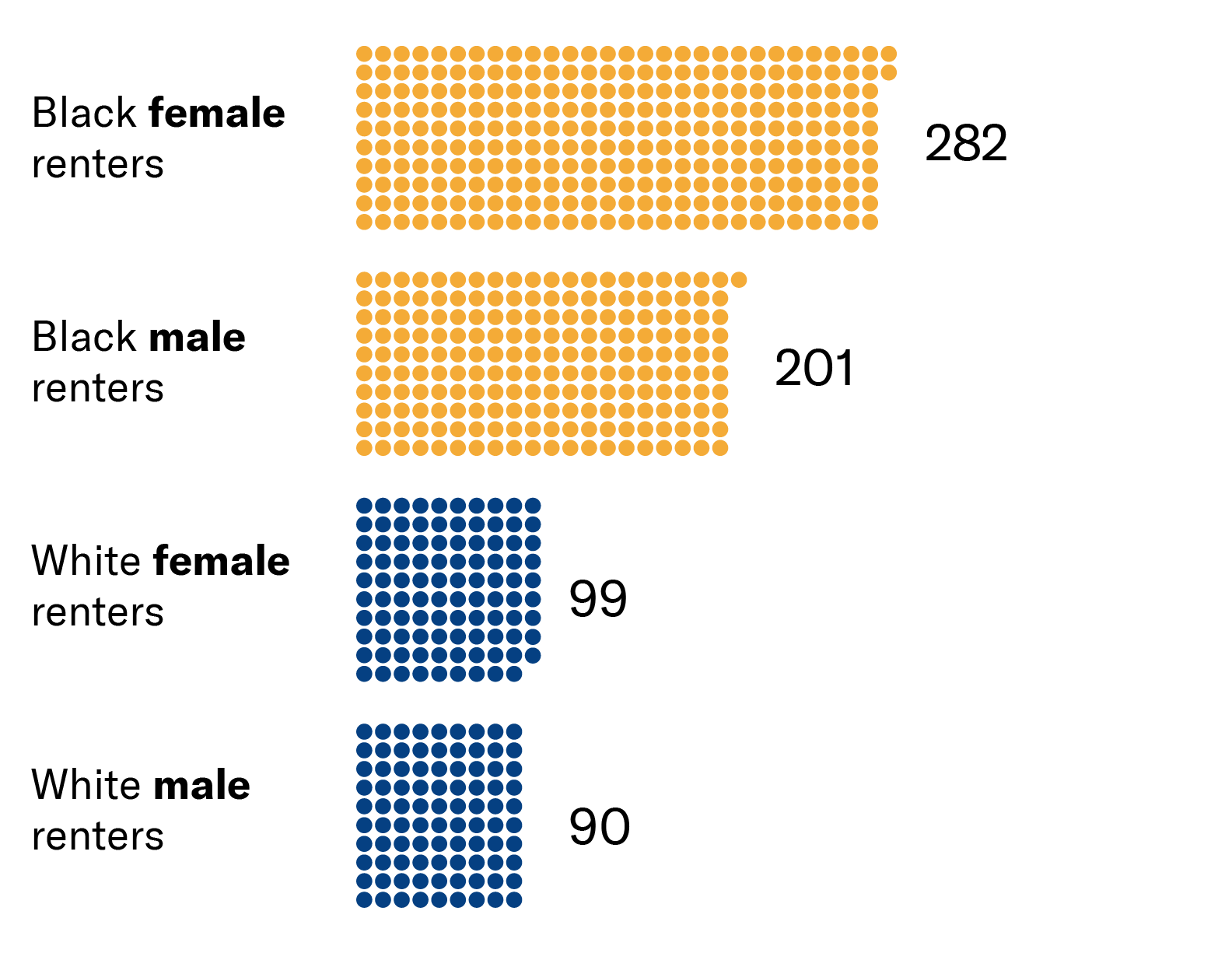

Black women face the greatest risk of having an eviction case filed against them in Massachusetts. Just under 500 in every 10,000 Black female renters in Massachusetts have an eviction filing, as compared to just under 420 in every 10,000 Black males, and 200 white women. Women of color, and particularly Black women, are especially vulnerable to eviction for many reasons, including and . Moreover, racial discrimination often compounds other forms of discrimination --- such as discrimination against families with children and domestic violence survivors --- that disproportionately impact women. As a result, eviction and screening policies often exacerbate and reproduce conditions of economic insecurity for low-income women of color.

Our Data Analytics team also found that Black women were more likely to have a prior eviction filing that ultimately resulted in dismissal. In Massachusetts, nearly 300 in 10,000 Black women had evictions filed against them that were dismissed --- as compared to less than 100 in 10,000 white renters. In other words, Black women are more likely to be denied housing due to prior eviction filings, even when they won.

Black women in Massachusetts were most likely to have evictions filed against them that were later dismissed

Per 10,000 renters

Data compiled by the Eviction Lab was available for 11 of 14 Massachusetts counties. Data span 2012 through 2016, but not all counties had all 5 years of data available.

In light of these stark race and gender disparities, blanket policies that categorically deny any applicant with a prior eviction filing disproportionately harm Black tenants, and particularly Black women, in violation of the Fair Housing Act. Such policies unfairly lock tenants out of housing opportunities without providing any chance to explain their circumstances or why they would be good tenants. With over two million evictions filed across the country each year, these policies have devastating consequences for the most vulnerable and marginalized in our communities.

Dismantling Barriers to Housing by Setting the Record Straight

Fortunately, there is a across the country --- led by tenants, organizers, advocates, and researchers --- to tackle the eviction crisis and its . Last summer, the ACLU of Massachusetts and ACLU Women’s Rights Project provided joint on — otherwise known as the HOMES Act (/) --- and Massachusetts legislators will have the opportunity to pass the bill this session.

The HOMES Act offers a powerful solution to the enduring impact of eviction for Massachusetts residents. The HOMES Act would require courts to automatically seal all eviction filings unless and until there is a final eviction judgment, thereby removing false positives from a tenant’s record. The HOMES Act would also provide for the automatic sealing of all eviction judgments after three years while allowing tenants to move to seal a prior eviction for good cause --- ensuring that tenants will not suffer indefinitely from the permanent stigma of an eviction record. The HOMES Act would further prohibit the use of a sealed record to deny housing or otherwise discriminate against tenants, combatting the unjust practice of tenant blacklisting and advancing fair housing principles.

Finally, the HOMES Act strikes an important balance by meeting the public interest in access to public records, while providing adequate protections against unjust barriers to housing for those who face a greater risk of eviction. The HOMES Act provides mechanisms for disclosing sealed records for journalistic, scholarly, educational, or governmental purposes after balancing the interests of the public and the parties in an eviction case. The Act further requires the court to maintain and make public aggregate data on eviction actions on a semi-annual basis, allowing the public to better understand the scope and scale of eviction in Massachusetts.

The HOMES Act is a critical step in a larger, national movement to eradicate unjust barriers to safe and stable housing for all. In 2020, Massachusetts legislators have the chance to take the lead in that movement and to provide valuable relief for its residents.

[1]Data were drawn from Lexis Nexis eviction court records and compiled by the Eviction Lab. Data consisted of millions of eviction cases in 39 states and spanned 2012 – 2016, but many counties and states had data available only for a selection of these years. 3,667 county-years containing 1,196 unique counties were available, making up, according to the Eviction Lab’s research, 37.5% of the renting population (see Hepburn et al., “Racial and Gender Disparities among Evicted Americans”, 2019, in progress). This is a representative sample of all U.S. counties among many key variables (renter-occupied housing units, median rent, Black or Latinx population share) but the sample includes counties with a higher white population and lower eviction rate than out-of-sample counties. Calculations provided are averages across these five years of available data.

Demographic characteristics, like race and sex, were imputed using defendant names and addresses. The and R packages as well as were used to predict probabilities for the likelihood a defendant was female or male – the average of the three probabilities was used. Relying on defendants’ last names and address, probabilities for race/ethnicity were imputed using the R package (Hepburn et al., “Racial and Gender Disparities among Evicted Americans”, 2019, in progress). Ultimately, each defendant was assigned a probability of being “male or female and of being white, Black, Latinx, Asian, or of another race/ethnicity” (Hepburn et al., “Racial and Gender Disparities among Evicted Americans”, 2019, in progress). Sex probabilities were multiplied by race/ethnicity probabilities to categorize defendants by race and sex – these probabilities were summed up to the county-year level.

Demographics of the adult renting population in counties with available data were estimated using Integrated Public Use Microdata Series data because the Census does not report race/ethnicity by sex estimates. The smallest geographic unit available was the “Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA)”, which was aggregated to the county level (Hepburn et al., “Racial and Gender Disparities among Evicted Americans”, 2019, in progress).

[2]States excluded entirely from analysis due to lack of sufficient data were Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. States additionally excluded from the map were Oklahoma, Tennessee and Wyoming, due to Black populations of < 1% in the counties with data available.

[3]Data was available for all Massachusetts counties except Plymouth, Bristol and Nantucket.

[4]Black renters made up 11% of the adult renting population in the counties with data available.