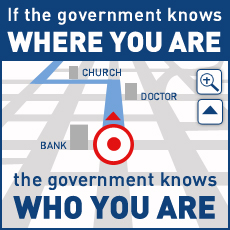

Yesterday the Supreme Court heard argument in an important case that confronts how to apply Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable searches and seizures to new technologies. Although the specific issue in the case, , is whether the government violated the Constitution by attaching a GPS device to a suspect’s car and tracking his every move for 28 days without a valid warrant, its impact could extend well beyond this circumstance because these days virtually all Americans carry cell phones that track our every movement.

To those of us sitting in the courtroom yesterday, it was readily apparent that many of the justices were deeply concerned about the impact on privacy of allowing all police officers unchecked discretion to track anyone they please for as long as they like for any reason at all, with no court supervision. Confronted with this sweeping claim of authority, Justice John Roberts asked the government attorney whether a consequence of its proposal was that police officers would be free to install GPS tracking devices on the cars of each of the nine justices. (It is.) And Justice Anthony Kennedy asked whether the government would also be free to attach a GPS device to a person’s overcoat and track their movements in public. (Yes.)

The justices also revealed themselves to be keenly aware that the Jones case is an early example of the ways in which intrusive new surveillance technologies are wreaking havoc with the long-established rules that restrained police surveillance in the pre-digital age. Justice Samuel Alito expressed concern that deciding this case on the narrow ground that physically attaching a GPS device to a car violates the Constitution would make the ruling quickly obsolete in an era of car navigation systems that allow companies to record our every move. And Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out that cell phones can also be used to track location.

In our friend-of-the-court brief, the ACLU asserted:

Unless this Court concludes that GPS tracking is a Fourth Amendment search, any individual's movements could be subject to remote monitoring, and permanent recording, at the sole and unfettered discretion of any police officer. Without judicial oversight, the police could track unlimited numbers of people for days, weeks, or months at a time. Americans could never be confident that they were free from round-the-clock surveillance of their activities. With a network of satellites constantly feeding data to a remote computer, police could, at any instant, determine an individual's current or past movements and the times and locations that he or she crossed paths with other GPS-tracked persons.

The Court should require the government to get a warrant before tracking people’s locations through GPS. A decision is expected in the case by June 2012.

Learn more about location tracking: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .