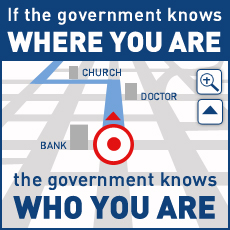

Federal law enforcement has used people’s cell phones to track their movements for at least a decade, but even today there is no clear answer to whether the government needs a warrant to do so. Why? In part because the U.S. Justice Department appears to be pursuing a conscious strategy of trying to avoid a ruling on this question by a court of appeals.

Here’s how that happens: Federal agents track people without a warrant, and in some instances, are slapped down by some district courts for this (in our view and in the view of these district courts) unlawful behavior. But they refrain from taking those losses to the Courts of Appeals, perhaps because a ruling that they need a warrant would then become the law of the land in the territory of that appeals court, and they want to be able to continue to engage in warrantless cell phone tracking whenever they can.

This is not how the system is supposed to work. It deprives the appeals courts of the opportunity to fulfill their role of setting uniform standards, which in turn deprives the American public of their right to know whether the government needs a warrant to access such sensitive information.

We were pleased when the government recently filed such an appeal—and disappointed when it withdrew the appeal shortly after the ACLU had been granted leave to participate in the case. The lower court had that the Fourth Amendment required the government to get a warrant when it sought to obtain at least 113 days’ worth of a person’s past movements from his cell phone provider. That was the right call because where people go reveals a great deal about them, and the Fourth Amendment needs to keep pace with changing technology. As Judge Garaufis wrote:

The advent of technology collecting cell-site-location records has made continuous surveillance of a vast portion of the American populace possible: a level of Governmental intrusion previously inconceivable. It is natural for Fourth Amendment doctrine to evolve to meet these changes.

When the government appealed, the ACLU, the New York Civil Liberties Union and coalition partner the Electronic Frontier Foundation were granted permission to present the arguments in favor of privacy to the appeals court. We were ready to explain why the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures forbids the government from obtaining cell phone location information without a warrant.

Unfortunately, the government has now withdrawn its appeal. We don’t know why it did so, but we do know the consequence: the chaotic state of the law will not be clarified. Whether the government needs a warrant will depend on which judge is on duty. This is not how the justice system is supposed to work.

The Justice Department persists in its strategy of not appealing cell tracking losses even though lower court judges have practically begged for the government to do so. Way back in 2005, “the full expectation and hope that the government will seek appropriate review by higher courts so that authoritative guidance will be given the magistrate judges who are called upon to rule on these applications on a daily basis.” Other judges have issued similar calls more recently, but to no avail. (The sole time the government did appeal a loss, the results were decidedly mixed.)

The American people deserve better. The government tracks cell phones all the time and all over the country, and whether it can do so without a warrant is a crucial Fourth Amendment question. Fortunately, the Justice Department has another shot. It recently filed a notice of appeal of a loss in a cell tracking decision in Texas. Let’s hope this time that it doesn’t withdraw it, and that the court has a chance to weigh in on a question of great importance to every American who carries a cell phone.

You can learn more about our efforts to uncover how law enforcement is using cell phone location data to track Americans, and can to support pending legislation that would require law enforcement to get a probable cause warrant before accessing location information and would also regulate the use of this information by businesses.

Learn more about location tracking: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .