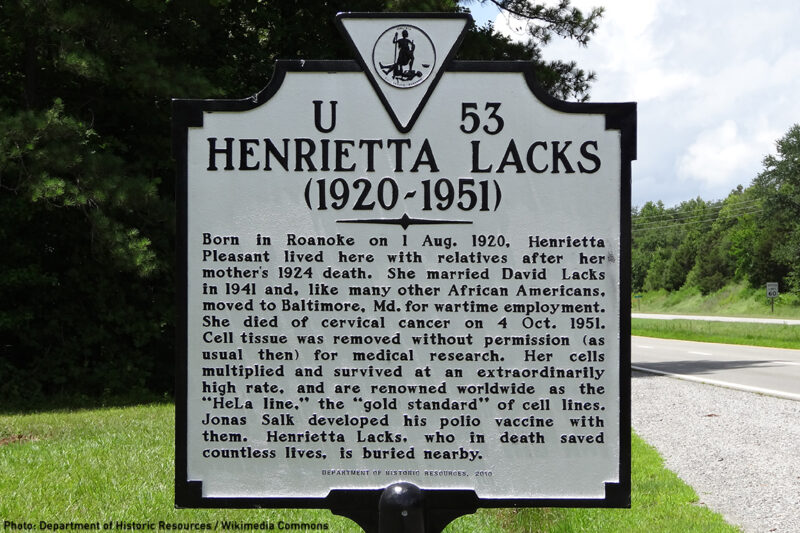

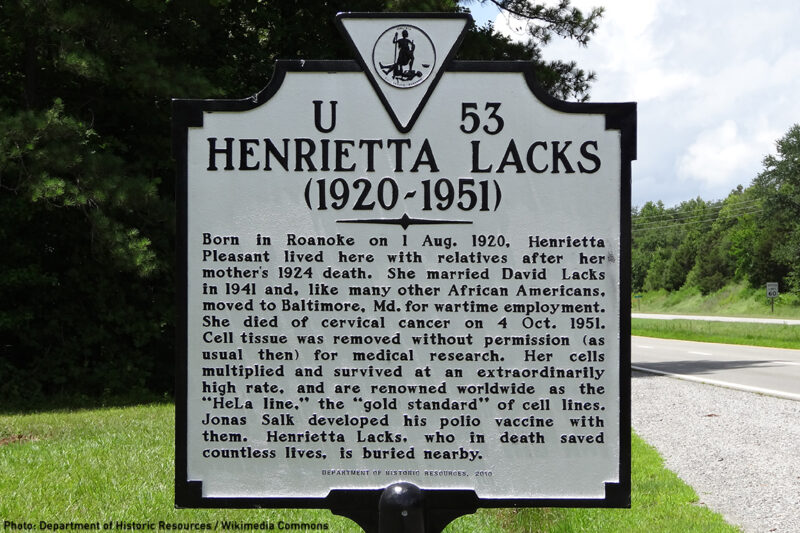

Henrietta Lacks’ Story Is a Powerful Lesson That Patients Deserve Full Control of Their Genetic Data

In 1951, doctors harvested cells from Henrietta Lacks while she was receiving treatment for cervical cancer and discovered that her cells had an amazing capacity to reproduce. “,” which aired last weekend on HBO and is based on the book of the same name, tells the dramatic story of how scientists used the “HeLa” cells in research for decades without the knowledge of her family.

Because of the book and film, the story of the Lacks family’s fight to understand and influence how Henrietta’s cells are used is finally getting the attention it deserves. But echoes of what she went through exist to this day, as I learned when navigating my own family history of cancer.

I have lost many family members to breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. Three years ago, when I was 52 years old, I was diagnosed with advanced bladder cancer. After some family members obtained genetic testing, I decided to do the same, and some of us tested positive for an uncommon mutation of the BRCA1 gene. The gene is most known for its connection to hereditary breast and ovarian cancers, but it also has been linked to prostate and pancreatic cancers. Scientists have not yet determined whether it may be linked to increased risk for bladder cancer.

Most Americans likely don’t know that when an individual gets genetic testing, he or she is often unknowingly contributing to a specific laboratory’s database of genetic information. Most patients would likely be happy to provide their data, with consent, for important scientific research. But, in most cases, the lab handling the test controls the data they obtain from individuals. They can refuse to share it with the scientific community, and they can choose to protect their own market position at the expense of scientific progress — and the very patients who paid them to conduct genetic testing.

I ordered my genetic testing from Myriad Genetics, which had that were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013. But while the gene patents were in effect, Myriad monopolized BRCA genetic testing in the U.S. The company built an exclusive mega-database containing enormous amounts of information from patients who had their DNA tested. To make matters worse, Myriad also this information with the larger scientific community, thereby stymieing important research that could lead to medical advancement.

Just last week, Myriad a study that claimed its database is superior to government databases for BRCA genetic testing. But the study only underscores how Myriad is holding the data hostage rather than collaborating with others, more interested in cornering the market and increasing its profits than helping patients. It should be noted that virtually every other lab doing this type of testing shares data with public databases — thereby providing the raw materials for medical breakthroughs.

Many patients want to be able to contribute their genetic information to research. And current guarantee patients’ rights to access their genetic data from testing labs. In practice, however, patient requests are often rebuffed. Patients requesting genetic testing may receive, for example, an overview of the findings, but often they do not receive the full data set in a format useful for researchers.

That’s what happened to me when I first requested my genetic information from Myriad. With the support of the ACLU, I have joined with others to make sure that patients can get the full results of their genetic tests in a format we can share with researchers. Patients should have the same rights to our genetic information as we do to other types of health information, so that we can make decisions about our own care as well as contribute our data to research if we so choose.

The struggle of Henrietta Lacks and her family needs to be remembered for the lessons it imparts about the need to safeguard patients’ privacy and consent. We must use all we have learned from the ethical issues surrounding the HeLa cells to inform today’s fight for patient control of our own genetic data to help fuel the next round of scientific breakthroughs.