The Orlando police department recently sketches of a suspect in the 2001 murder of a woman named Christine Franke. The sketches were not based on witness memories or surveillance video, but on a sample of DNA found at the crime scene and believed to belong to the killer. The suspect’s DNA genotype (genetic code) was analyzed in an attempt to predict what his phenotype (actual physical characteristics) would look like—specifically his face.

What should we think about this?

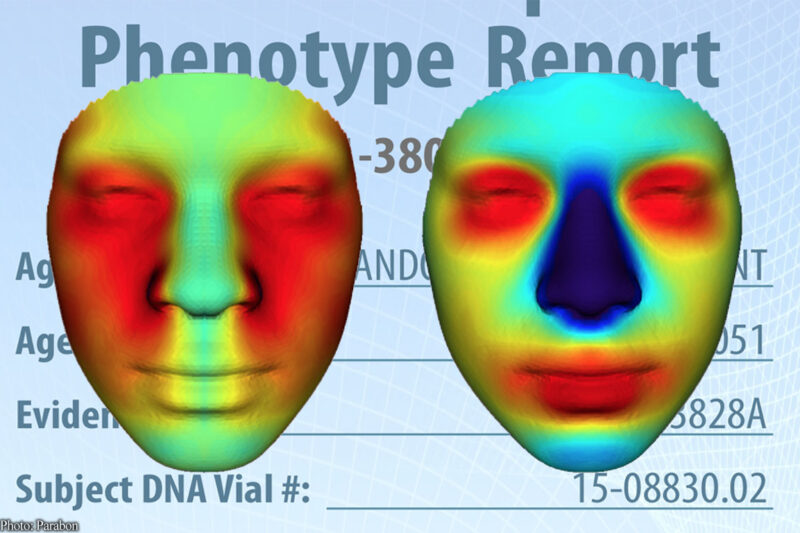

The image was produced by a company called Parabon, which was paid $3,600 by the Orlando PD for the “Snapshot” analysis, paid for by a federal grant. In its report (which we have posted here), Parabon examines the crime-scene DNA to predict the genetically male suspect’s skin color, eye color, hair color, and presence or absence of freckles. The company also provided his genomic ancestry results, similar to what you can get from a commercial family DNA analysis service, indicating the geographic areas of the world from which his ancestors came.

Parabon also provided what they called their “face morphology results”—the sketches released by police. This part of the report claims to identify phenotypes such as “larger mouth and brow,” “wider face,” “slightly narrower chin,” and “higher nose tip; lower eyes and brow.” The result is the subject’s “predicted face” —the full-color, near-photo-quality computerized image released by police appears to be a very generic-looking black man.

The problems with this approach are many. First, one’s looks are not purely a result of one’s DNA. You can dye your hair or shave it off, grow a beard, eat well or poorly, lose or gain weight, become a drug addict, get disfigured in an accident, get too much sun, smoke, lighten or darken your skin, have plastic surgery, change gender, and do many other things that can affect your appearance but which have zero tie to your facial DNA. And although it may become possible, DNA analysis does not currently indicate a subject’s age. This analysis included two images, one of the subject at age 20 and another imagined to be age 40.

More fundamentally, the science apparently just isn’t there to support using genes to figure out how they will make someone look. The New York Times experts what they thought of DNA phenotyping of faces last year; quoting Kenneth Kidd, a professor of genetics at Yale, the Times noted that

he and other experts are skeptical that faces, which are very complex, can be determined from DNA. While inheritance clearly plays a big role – identical twins look alike, obviously, and people resemble their close relatives — some experts say not enough is known yet about the relationship between genes and facial features.

“A bit of science fiction at this point,” said Benedikt Hallgrimsson, the head of cell biology and anatomy at the University of Calgary, who studies the development of faces.

The critics noted that Parabon, which is based in Reston, Va., and has received grants from the Defense Department, had not published information in peer-reviewed journals validating its methods, even though such a publication would increase sales.

Parabon’s report to the Orlando police contains an extensive disclaimer, advising its law enforcement clients that their “prediction models do not represent the full range of human genetic diversity,” that environmental factors “can affect appearance in ways that are inherently unpredictable,” and that “discretion should be used when attempting to include or exclude individuals in an investigation by comparison of appearance with Snapshot predictions.” When the New York Times of the Parabon system with one of its reporters, it failed badly.

Scientists say that some physical characteristics, such as eye and hair color, are relatively easy to pin down to genetics because a single gene has a big influence on the phenotype. Others, like height, are much more complicated, with environment seeming to play a much bigger role than any genes so far identified.

Overall, our recommendations on this issue are:

- Face reconstructions based on DNA phenotyping should not be used for any serious purpose or advertised to the public as a suspect, unless and until the science becomes very firmly proven and established. Such reconstructions are still science fiction, and putting out an image of a generic face with such a tenuous connection to reality is not “trying every avenue,” it’s issuing baseless information that risks ensnaring innocent people within webs of suspicion and/or investigation.

- When a suspect is believed to be a person of color, it also risks dovetailing with existing societal prejudices to further increase the risks to innocent people.

- The actual suspect may look nothing like the speculative image, which could end up detouring or otherwise harming an investigation.

- There is also a danger that some less scientifically sophisticated police officers will give excessive credence to these speculative reconstructions, attempting to use them in whole or part to establish probable cause, or to pressure people to “voluntarily” provide DNA samples or submit to other intrusive investigatory techniques.

In some circumstances it may make sense to use genetic phenotyping in an investigation, but:

- Only where the link between genes and external characteristics is based on well-proven, peer-reviewed, widely accepted science, such as is apparently now the case with hair and eye color.

- Only where such evidence is used in conjunction with other, more specific evidence. It may be helpful to narrow down suspects, but it is not specific enough, and should never be used, to create suspects where none are otherwise known.

- It should not be used to pressure people to “voluntarily” provide DNA samples or to submit to any other intrusive investigatory techniques. We don’t want police using these genetic analyses to run around conducting dragnets for every person in a neighborhood with black hair, hazel eyes, and freckles, for example.

- It should not be considered to constitute probable cause. Even in the case of a DNA sample that reveals that a suspect has albinism or some other particular genetic condition—perhaps a rare one—that fact should not be used to pour through hospital records, for example.

My heart goes out to Franke’s family, and I can understand how desperate they must be for a resolution in her case. And it’s commendable that Orlando detectives continue to work to find a resolution in this 15-year-old case. But this “science fiction” face-reading technique should not be part of their arsenal, or other police departments’ in similar investigations.