The Associated Press ran a (along with ) this week on the use of voiceprints by big banks and other institutions. Those companies say they are using the technology to fight fraud, but in the process they are apparently compiling large databases of voiceprints without customers' knowledge or permission.

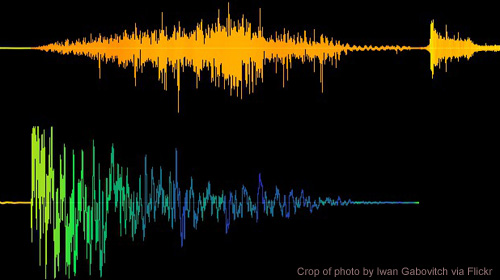

Voiceprint recognition is the use of to recognize the timbre of a person’s voice. It is a technology I was aware of, but I did not know that it was being used so widely—and I suspect few Americans did. This technology raises a number of issues:

- Effectiveness. Although vendors of course tout its accuracy, it's not clear what the rates are for this technology as deployed in the real world by the banks. It could well be effective enough to increase banks' profits, but still have a high enough error rate that particular individuals get unfairly treated due to false-positive matches with fraudsters. In the national security context, the consequences of false positives could be much more serious—including in some circumstances even death. As the Intercept , the NSA has used its "state-of-the-art" voice recognition systems to help the Turkish government kill Kurdish rebels (or, we should say, those believed to be Kurdish rebels).

- Consent. It's one thing if a company says, "If it's okay with you, we'd like to use your voiceprint to authenticate you, and if you don't want to participate, here's another method we can use." It's quite another for companies to be compiling large databases of voiceprints without customers' knowledge or permission. The AP obtained an internal document that recommended that "this call may be recorded" notifications be supplemented with "and processed" to cover the collection of voiceprints—hardly genuine notification. Enrollment in a biometric database is something that, by global consensus, should generally not be done without subjects' meaningful knowledge and consent.

- Security. It's not clear how easy it would be to spoof or otherwise defeat voiceprint systems. Current deployments by banks may be based on an assumption that the technology is not widely known about or understood, but such ignorance of course never lasts, and human beings are clever at finding ways to game things. What if a fraudster figures out how to spoof your voice and empties your bank account? And possibly lands you on a blacklist to boot.

- Anonymous speech. This technology promises to erase yet another major avenue for anonymous speech, which has been a core American speech tradition at least since the publication of The Federalist Papers and other anonymous colonial writings. Sometimes people need to make anonymous phone calls—to call in a crime tip, for example, or to call a psychological support hotline. (True, caller ID has already made this more difficult, but it is still doable.) When an individual calls a radio talk show, their caller ID may be apparent to the station, but they are not generally identified by full name on the air. The possessor of a giant voiceprint database listening to the radio, however, could identify those callers, and gather information about their opinions. If people lose faith that they can be anonymous in various contexts, that will create chilling effects that will impoverish our society.

- Tracking. A database of voiceprints is in some ways just another compilation of valuable personally identifiable data, and is susceptible to the full range of uses to which such databases are often put. One can imagine its use to identify shoppers as they chat in the aisles, for example. I have written before about the threat that surveillance cameras will begin featuring microphones collecting audio from public spaces; this technology sharply increases the stakes of that battle.

In many ways the closest parallel to voiceprint technology is face recognition. In both cases, unique attributes that we cannot help but project out into the world are recorded and analyzed by powerful institutions. Regulating the collection of such data can be tricky, but we have every right to expect that institutions that are supposed to answer to us (as customers or citizens) will be honest and transparent in how they are doing so.

Ultimately, the question with this technology, as with any tracking technology, is whether and in what ways its use will go beyond the narrow goal reported by the AP of trying to stop fraud, and how any such uses are likely to affect innocent people, be used for social control, and shift power from individuals to large institutions.