Assessing the legacy of the Fair Housing Act on its 45th Anniversary.

As we celebrate the 45th anniversary of the landmark Fair Housing Act, it is easy to forget how close we came to being denied the benefit of that landmark legislation. After Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1965 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, civil rights supporters were met with fierce Congressional opposition to extend federal anti-discrimination protections to housing. That years-long resistance was only overcome by the anger and frustration that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King and the growing sense of unfairness that Americans of color could be asked to die in Vietnam but could not rely on the promise of fair housing back in the United States.

Perhaps the resistance to non-discrimination in housing arose from the realization that fair housing involves far more than creating a right to obtain shelter. Our address can determine whether our children attend quality schools or are consigned to overcrowded, underresourced ones. Whether we have access to transportation, employment, fresh food and vegetables, and a safe and clean environment can be determined by where we live . Where we live determines the extent to which we have access to the opportunity to realize the American Dream.

The Fair Housing Act has played an enormous role in addressing the wide-ranging effects of housing discrimination. No longer do we see advertisements for housing containing race and ethnicity restrictions. And although tests conducted by fair housing groups still uncover residual discriminatory practices, the Fair Housing Act assures that property owners or brokers who discriminate do so at their peril. Landmark housing cases such as Hills v. Gautreaux and Thompson v. H.U.D created mechanisms for families formerly housed in projects in Chicago and Baltimore to have access to safe housing in areas with high quality schools, and demonstrate the ability of the Fair Housing Act to open doors of opportunity.

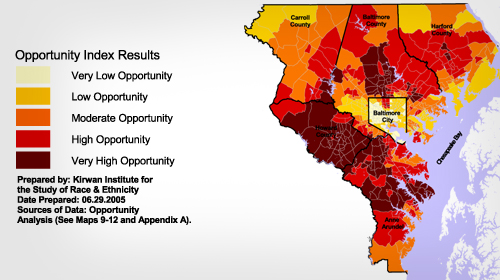

HUD’s issuance of rules prohibiting many policies which have a disproportionate impact on communities of color and not just ones involving intentional discriminatory treatment have also contributed to the vitality of the Fair Housing ActIn spite of efforts over the past four and a half decades, numerous studies have shown that the housing market in the United States remains deeply segregated. And this segregation is far from benign. When social scientists have superimposed maps of racial and ethnic distribution on maps showing unemployment rates, exposure to hazardous environment, or access to employment, high quality schools, and health, it reveals a cruel geography of exclusion and deprivation.

Those powerful, adverse effects are the result of current and historical actions. Adkins v. Morgan Stanley, a case brought recently by the ACLU shows that a legacy of hyper-segregation in Detroit combined with a history of red-lining and lack of access to funding options made African-American homeowners in the area particularly vulnerable to greedy and unscrupulous mortgage lenders. In its description of the highly disproportionate foreclosure rates to which these homeowners have been subjected, the case is a sad demonstration of the way that the seeds of prior discrimination continue to bear bitter fruit.

As he signed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, Lyndon Johnson observed “We have come some of the way, not nearly all, there is much yet to do.” Sadly, that statement continues to be true. But even if we cannot celebrate the 45th anniversary of the signing of the Civil Rights Act as an occasion to commemorate the eradication of all of the effects of discrimination in housing, we can rejoice in the fact that the protections offered in the Fair Housing Act hold out the promise and the means of eliminating this particular form of injustice.

Learn more about housing discrimination and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .