Over Independence Day weekend, I joined hundreds of fellow Japanese-Americans at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage. Held on the site of the Tule Lake Segregation Center, this pilgrimage offers a chance to remember how the U.S. government imprisoned our families without trial during World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt provided the legal authority for this incarceration by signing Executive Order 9066, which directed military officials to “prescribe military areas . . . from which any or all persons may be excluded.” was facially neutral, in that it named no particular ethnic groups. However, everyone involved in its drafting and implementation knew it would target people of Japanese ancestry, both U.S.-born citizens and noncitizen immigrants.

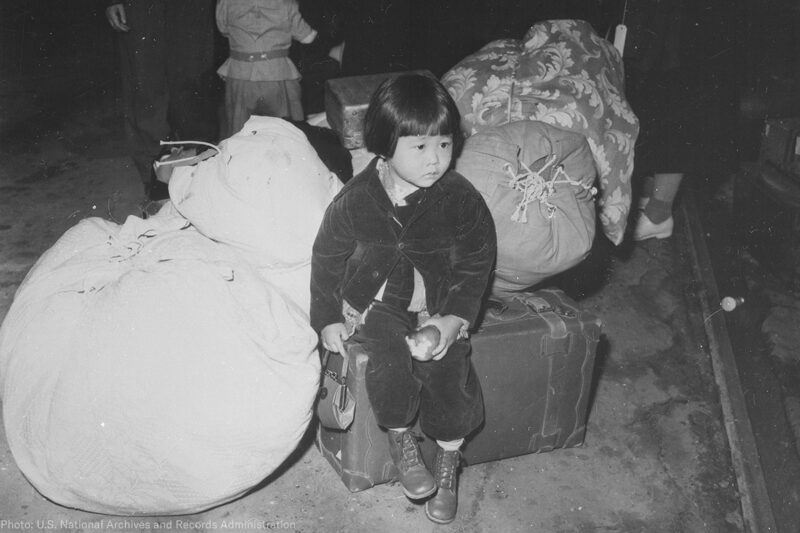

In the ensuing weeks and months, Lt. General John L. DeWitt — an avowed racist who famously declared that “a Jap’s a Jap” regardless of citizenship — designated large swaths of Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington as “military areas” from which Japanese-Americans would be “excluded” by force. As a result, my grandmother Bette — a 23-year-old aspiring fashion designer from a small California town — was forced to interrupt her junior college education to be imprisoned with her parents and siblings at the Tule Lake prison camp. They were assigned to tarpaper barracks to live behind barbed wire under the watch of armed guards. Meanwhile, my grandfather Kuichi — who had actually been drafted into the U.S. Army before Pearl Harbor — was left in an uncomfortable limbo while military authorities decided what to do with this newly enlisted soldier who happened to be of an “enemy alien” race. Eventually, they ordered him to join the fight in Europe.

In the years that followed, a handful of Japanese-Americans pursued legal challenges to the various orders that Lt. General DeWitt issued under EO 9066, including curfews, travel restrictions, and ultimately the roundup and incarceration of Japanese-Americans. The first to be decided by the Supreme Court were and in 1943, which approved the race-based curfews. The last were its 1944 decisions in , which avoided deciding the constitutional question, and , which approved the final roundup as constitutional. Writing for the majority in Korematsu, Justice Black asserted:

“To cast this case into outlines of racial prejudice, without reference to the real military dangers which were presented, merely confuses the issue. Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire.”

Three justices saw the folly and danger of this blinkered approach. Justice Roberts characterized the case as “a clear violation of Constitutional rights.” Justice Murphy described the racist origins of the orders and wrote bluntly: “I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism.” And Justice Jackson wrote a prescient warning about the dangers of “a judicial opinion [that] rationalizes such an order to show that it conforms to the Constitution, or rather rationalizes the Constitution to show that the Constitution sanctions such an order.” Once racial discrimination has been validated by the highest court, that principle “then lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

Meanwhile, at least 331 people died while incarcerated at Tule Lake under the authority of EO 9066. Those not cremated were buried in a cemetery inside the camp’s perimeter. It is not possible to visit that cemetery today. After the war, local residents bulldozed the graveyard and used the soil and bones as construction fill. All that remains is a lumpy depression in the ground, next to what is now the county dump.

I read the Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. Hawaii, the lawsuit challenging the third iteration of Trump’s Muslim ban, on my way to the Tule Lake Pilgrimage. And I could not stop thinking about that graveyard and its desecration.

In Trump, the court upheld the Muslim ban despite overwhelming evidence that it was motivated by anti-Muslim prejudice. Yet the court simultaneously repudiated Korematsu v. United States, writing that the 1944 decision “was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—‘has no place in law under the Constitution.’” But this did not truly lay Korematsu to rest.

The Supreme Court justices who signed the majority opinion may believe their words buried Korematsu in the graveyard of history. But Korematsu was already resting in a shallow grave and nearly completely repudiated. What they actually did was to deliver a eulogy even as they disinterred its bones and infused its spirit into another injustice.

In Trump, Chief Justice Roberts contended it is “wholly inapt” to liken the “forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race” to the Trump administration’s “facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission.” Yet the mental gymnastics that the Trump court went through to avoid finding religious animus are virtually the same as those the Korematsu court employed to avoid finding racial animus.

As Justice Sotomayor wrote in dissent:

Moreover, as legal scholar Eric Muller , the narrowness of the court’s repudiation of Korematsu leaves the identical reasoning of Hirabayashi (holding that the race-based curfew was “not wholly beyond the limits of the Constitution and is not to be condemned merely because in other and in most circumstances racial distinctions are irrelevant”) intact and free to be cited by future decisions.

Thus, the Supreme Court’s disingenuous funeral ceremony for Korematsu gives me no comfort as a Japanese-American. Instead of truly putting Korematsu to rest, the Muslim ban decision revived Korematsu under another name. And the re-animated spirits of Korematsu and the other Japanese-American incarceration decisions will continue to roam American jurisprudence until Trump v. Hawaii receives its own funeral rites.