I’m Suing Texas Because the Legislature Passed a Bill That Discriminates Against My Town

I was born in Corpus Christi and I first came to live in the border town of El Cenizo as a 9-year-old kid. At that time, the place had just incorporated as a town after being a colonia, an informal community without running water or electricity. Most of the people I grew up with were U.S. citizens, like me, but everyone had Mexican roots.

The life we lived was “in between”: I put ketchup on my huevos revueltos, I listened to cumbias texanas, and I played trumpet in my high school band. People’s contributions mattered — their kindness to neighbors, their work on clean-up crews, their payments of municipal taxes to help build our town — not their immigration status.

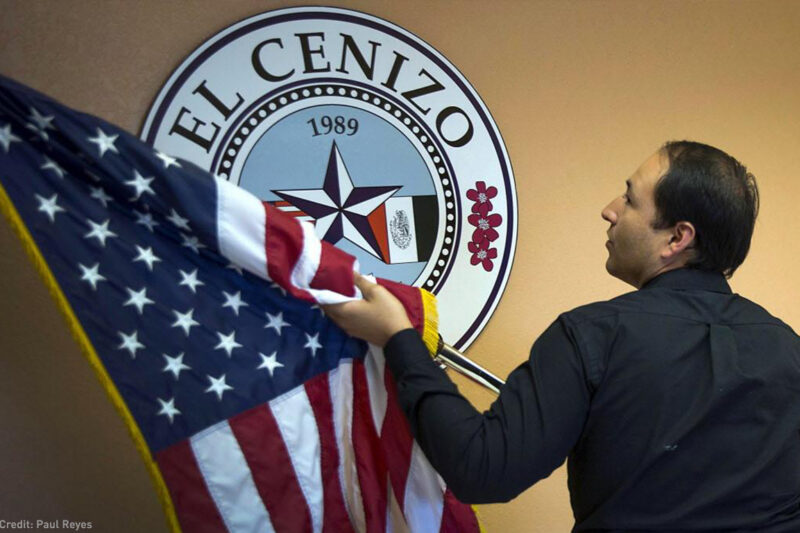

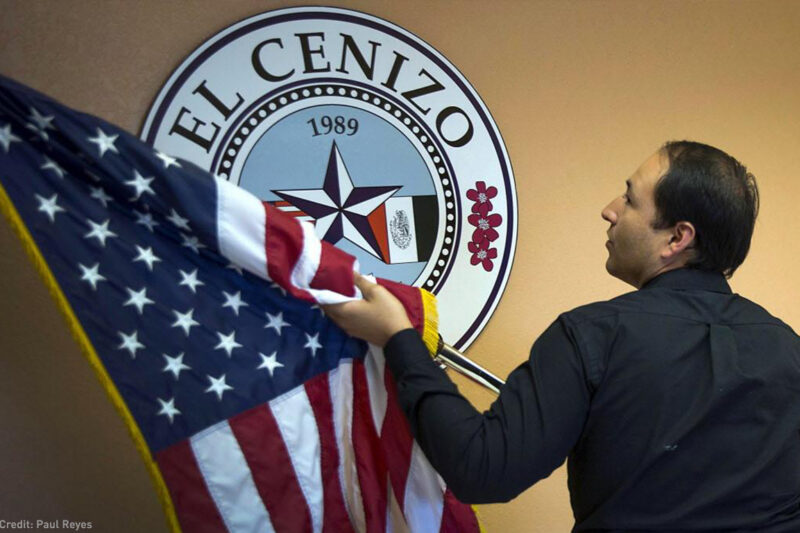

Now I’m mayor. I’m suing the state of Texas because of a new law, Senate Bill 4, that would give a green light to police officers to investigate a person’s immigration status during routine events like traffic stops. I believe this would lead to widespread racial profiling and illegal arrests of citizens and non-citizens — people like the residents of El Cenizo, including me. Any of us could be mistaken for foreigners because of the way we look and speak. Many people from my town who are U.S. citizens don’t speak English — why should they have to prove their right to be here, and how would they do it?

The law would also prohibit our municipality from adopting any policies that ensure all individuals, including those who are undocumented or have undocumented family members, feel comfortable working with our officials — even though we have had policies against asking questions about residency status since 1999. And the law would allow state officials to fine, jail, and remove from office any elected or appointed official who limits cooperation with federal immigration officials. My mother, for one, is worried that will be me.

For years, I thought El Cenizo was on a steady path of progress. All over Texas, colonias improved materially, and their people gained more opportunities.

When I first came to El Cenizo as a child, things were very different. I remember when it rained heavily, our streets were like little flowing rivers that were our swimming pools; we would let the water current drag us to the end of the street. Our house was a structure of concrete floors, four walls, and a roof, with no insulation or windows. On cold winter nights, we’d shove the two beds together and sleep crammed in all together, wearing almost all the clothes we owned, just to keep warm. Immigration agents were a constant presence, and people were frequently harassed and sometimes abused.

Now all of our streets are paved, we have some sidewalks, we have plenty of street lights, and we’ve built a park and a library. We have a small fire department, and a police department with three to five officers. Regardless of their immigration status, people feel free to walk down the street or report a problem to the police.

Cops here concern themselves with issues that are important for our community. They’ll knock on your door if you have an old sofa in your yard, if you’re not cutting the grass, or if you’re keeping chickens or goats. Our police officers also handle traffic stops and risk their lives intercepting illegal narcotics that have crossed the Rio Grande.

We have amazing officers, and they do great work. Their role should not be to enforce immigration rules.

El Cenizo is very safe. We are not overrun by “bad hombres,” as President Trump would have you believe. I’ve been in office 13 years and I’ve yet to see a homicide here. In my experience in El Cenizo, undocumented people are extremely unlikely to commit crimes. Typically, undocumented people have other things to worry about: how to find enough work, hold down two or three jobs, provide a better future for their children.

We’re already feeling the consequences of people’s fear of SB4. People are scared. They’re making adjustments to their lives to avoid contact with the police. Reports of domestic violence are down in my community, and other crimes might go unreported too. I’m worried that will make this place more dangerous for all of us.

But SB4 is bigger than El Cenizo, or even Texas. This is about what sort of country we want to live in. Will we choose to live in a country where our laws encourage law enforcement agents to target people because of the way they look and sound?

It feels frustrating and sad to see a country I love so much take backwards steps into our history of deep discrimination. When legislators create laws that legitimize that discrimination, it trickles down. Social media feeds and comment sections on news sites are full of hate. I saw a video where a U.S. citizen speaks to his mom in Spanish, and people start chanting, “Go back to Mexico!”

Still, since I moved to sue the state, it’s also been very moving to see people reaching out. I have a stack of postcards and notes I’m keeping from people in places as far away as Alaska and California who’ve gotten in touch to express their support. One woman from Fredericksburg, Virginia, wrote, “It’s heartbreaking to see all the changes in our country,” and stapled a check for $40 to put toward our town’s legal expenses.

I keep that letter on my desk. I’m planning to write back and tell her that during a time of hate and division in our country, her words inspire me to keep fighting.

Raul L. Reyes is the mayor of El Cenizo, Texas.