Last summer, the Obama administration announced its plans to open new immigrant family detention centers in response to the wave of women and children fleeing violence in Central and South America and seeking asylum in the United States. The ACLU and other advocacy groups quickly opposed the White House's policy because of the harm it would inflict on already traumatized women and children. This month, The New York Times editorial board described family detention simply as "," and the U.N. Human Rights Council the U.S. to "halt the detention of immigrant families and children." In the following piece, psychotherapist Satsuki Ina, who was born in a Japanese-American prison camp during World War II, recounts her visits to two so-called family detention facilities in Texas and the psychological toll detention takes on the women and children imprisoned there. — Matthew Harwood

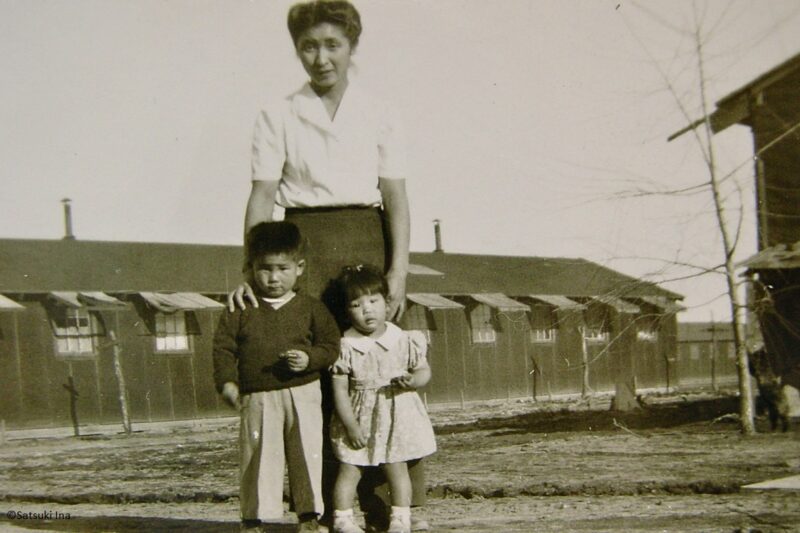

I was born behind barbed wire 70 years ago in the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a maximum-security prison camp for Japanese-Americans in Northern California. My parents’ only crime was having the face of the enemy. They were never charged or convicted of a crime; yet they were forced to raise me in a prison camp when President Franklin Roosevelt signed a wartime executive order ultimately authorizing the incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent. We were deemed a danger to the “national security” and incarcerated without due process of law.

When the war ended, my family was moved to a prison camp in Crystal City, Texas, and finally, after a total of 4 years of captivity, we were released. Decades later, our government acknowledged the injustice that had been committed. I never expected to return to Texas, and I certainly never expected to see other families incarcerated just as my own family had been 73 years ago. But this past year, the U.S. government created something that compelled me to go back.

Have we not learned from the past?

The Dilley family detention facility, just 45 miles away from my childhood prison, and another like it in Karnes City, about 100 miles further away, are new prison camps specifically dedicated to detaining women and children who are trying to escape horrific violence in Central and South America. At the Dilley dedication ceremony, Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson that the purpose of this facility was to deter families from fleeing to the United States and to send a message that “if you come here, you should not expect to simply be released.”

Message Received, Loud and Clear

My visit with mothers and children at the euphemistically named Karnes County “Residential Center” a few weeks ago triggered distressing associations of my own experience as a child. We too lived in a constant state of fear and anxiety, never knowing what our fate would be. We too were forced to share our living space with strangers, line up for meals, share public latrines, respond to roll call, and adjust to ever-changing rules and regulations with the eyes of the guards constantly trained on us.

As a licensed family therapist, I was appalled at the severity of the trauma that the women and children had experienced prior to their arrival in the U.S.

And even more disturbing was the evident criminalization of their efforts to escape violence and seek safety and protection for their children. To be imprisoned with their children — infants and toddlers, school age and teens — is not only unjust, it cruelly plunges them back into their past powerlessness and terror.

The visiting room was a large, sterile space with tables and chairs. In one corner was a shelf and carpet with a few toys. The children are allowed to play with the toys in the corner, but they were not permitted to bring the toys to the table where I sat with the moms. Few children chose to leave their mother’s side. The guard monitored the families as they entered the visiting room. Stern and ill-humored, she served as a strict timekeeper over the precious 60-minute visit the family was allowed.

One mother, whose eight-year-old daughter clung closely to her side, grew tearful describing her five-month detention with no idea when or whether she would be deported or released. She had a looming interview evaluating whether she could establish that she had, in fact, “credible fear” that her life and well-being would be at risk if she were deported. The mother mentioned that her daughter cries inconsolably for hours whenever one of her little friends leaves the facility. I asked the girl, who cautiously looked over her shoulder at the guard, to tell me what she thinks about when a friend leaves. In a whisper she told me that she’s afraid that her friend’s family may have been forced to go back to their home where they could be killed. I knew that she had witnessed repeated violence against her own mother in their home.

(Source: The Tule Lake Segregation Center, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.)

Mom told me that the child is afraid to go to sleep, often refuses to eat the food that is heavily seasoned with pepper, seems depressed and sad most of the time, and is becoming increasingly angry and disobedient.

I asked the child what it is that makes it so difficult for her to sleep. She checked her mother’s response and the whereabouts of the guard and, reluctantly, told me that she always thinks about the “giant scary dog” that was barking and growling right up close to her face. As she spoke she’s unable to hold back the tears that roll down her face. Mom, tearful, explained that it happened when they were picked up by the Border Patrol.

I took a tissue out of my pocket and offered to wipe her tears but she refused, shutting off her tears and withdrawing, a blank expression returning to her face. Desperately not wanting to lose contact with her, I remembered how to fold the tissue back and forth, peeling back sections of each sheet, to make a flower; I offered her this small gift. A smile filled her face, and in that moment, I saw the unguarded delight of a child as she held the fragile flower in her hand. But sadly, when the guard warned that the hour was almost up, she dropped her eyes, obediently standing and walking to the door that will be locked behind her.

Prison is no place for a child, and locking children up is inherently traumatic. Children are particularly susceptible to developing symptoms of trauma that persist long after the threat is removed. These often include hypervigilance, uncontrollable bouts of crying, sleep disturbance, and depressed mood.

We were deemed a danger to the “national security” and incarcerated without due process of law.

Current research clearly shows that early childhood trauma can alter the person’s nervous system and . In my work with Japanese-Americans who had been incarcerated as children, many reported struggles with anxiety and depression as adults. Particularly key was the environment in which they were held and the torment and suffering that they witnessed their parents experiencing. After years of my own therapy and education, I continue to have easily triggered startle responses, extreme vigilance in settings when I am the only person of color, and an anxious need for control in uncertain situations.

The women I spoke with at Karnes told me about the violence and cruelty that had been a way of life — husbands who have beaten or abandoned them, or gangs that have targeted them to extort money. They have suffered beatings, rapes, and betrayal with no hope that there will be protection from corrupt police. Now they come to America seeking safety and a better life, only to be locked up like the criminals they escaped.

The Trauma of Unnecessary Incarceration

When I discovered my mother’s prison diary 10 years ago, I learned that she lived with anxiety daily, not knowing how long we would be imprisoned. Would it be a few months? A few years? She never knew where we would be sent next. And she lived in fear of my father’s well-being after he was sent to a separate prison in North Dakota. Finally one day she wrote, “I wonder if today is the day they’re going to line us up and shoot us.”

She described the misery of being quarantined and confined inside the prison barracks for two months when my brother and I came down with chicken pox. Her constant state of anxiety about her children resulted in chronic illnesses that plagued her throughout her lifetime. I didn’t realize until decades later that she suffered from post-traumatic stress as a consequence of the incarceration. I wonder how many lives, just like my mother’s, the U.S. government is needlessly and cruelly damaging today for its ill-advised “family detention” program.

It has been a life-long mission for me to educate others about this dark chapter of American history with hopes that it would never happen again. The incarceration of innocent women and children seeking asylum in America tragically replicates the racism, hysteria, and failure of political leadership of 1942.

Have we not learned from the past?

Satsuki Ina is professor emeritus, California State University, Sacramento. She has a private psychotherapy practice in Sacramento and Berkeley specializing in the treatment of trauma. She produced two award-winning documentary films about the Japanese-American incarceration, Children of the Camps and From A Silk Cocoon.