A Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity: Why the U.S. Should Keep its Promise to Diversity Visa Winners

Update 9/14/2021: This week, the House Judiciary Committee will begin markup of immigration provisions in the Build Back Better reconciliation bill. As of Monday morning, the language restores access to diversity visas for people who were selected in the diversity visa lottery but were denied visas due to Muslim, Africa, and immigrant travel bans and COVID-19 related disruption. Now the fight continues to ensure the language stays in the reconciliation bill and becomes law.

I was six years old when I first saw the Statue of Liberty, on a trip to New York with my parents and two younger siblings. We were not tourists. We were immigrants about to embark on a new chapter of life in America, carrying immigration papers that felt like gold after winning the diversity visa lottery.

Today, thousands of people from around the world are being denied that same chance at the American dream because their winning tickets were torn up during the anti-immigrant Trump administration. While President Biden acted quickly to rescind the Muslim ban and the subsequent bans targeting African countries, his executive order diversity visa recipients from countries who were blocked under Trump’s bans. They are still waiting for the U.S. to keep its promise. They deserve better.

When my family won the diversity visa lottery, I was too young to fully understand the gravity of that moment. Still, I knew it was a big deal. It was exciting but also nerve-racking having to uproot ourselves from our home in Pakistan and move halfway across the world to a country where we had no relatives or connections. Families like ours cannot immigrate using common channels like obtaining visas through relatives already in the U.S. For us, the diversity visa was the only pathway to immigrate and eventually become citizens.

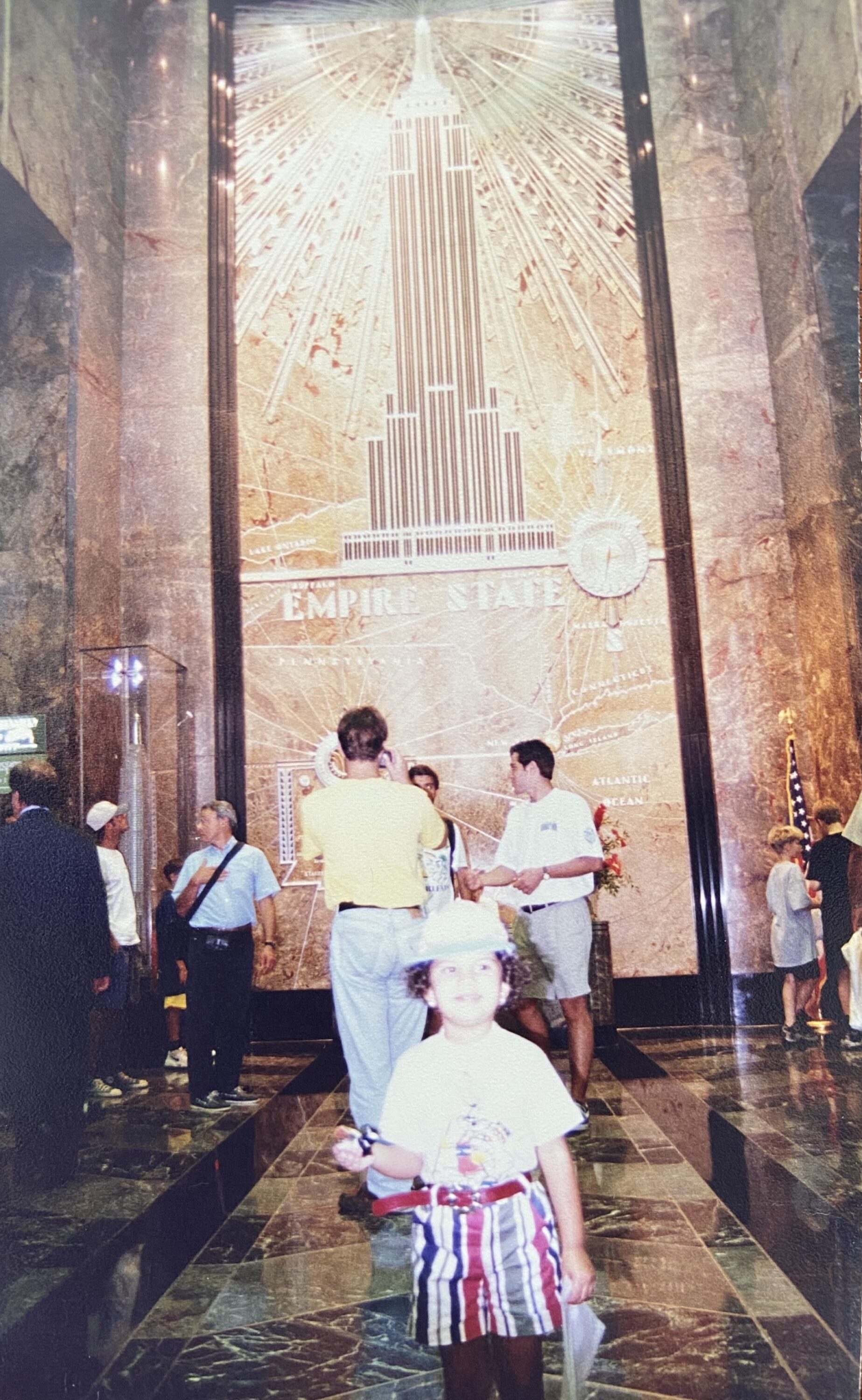

Mira Naseer in the Empire State building during her family's visit to New York City.

The Diversity Immigrant Visa Program was established in 1990 specifically to “diversify” immigration to the country, offering 50,000 visas annually to people from countries with low immigration rates to the U.S., who are selected randomly from a pool of pre-approved applicants who meet threshold criteria such as education and work experience. Applicants have a chance of winning. While many people apply every year to increase their odds of winning, my parents applied individually and waited for a year until miraculously, my mom won. Most applicants wait much, much longer, making my family’s luck all the more extraordinary.

Like so many parents across the world — especially those in Africa and Asia where most lottery winners are from — mine dreamed of immigrating to the U.S. so their children could access educational and economic opportunities we wouldn’t have elsewhere. And that’s what we did. Both of my siblings and I went to college in the U.S., and now I’m a student at Harvard Law School.

The experience also made me well-acquainted with the immigration system. From a very young age, I was exposed to all the paperwork, the green card renewals, and the offices of government agencies we frequented to maintain our status. When I visited family members living overseas, I quickly realized that I had certain privileges that came with the right paperwork. Those privileges ranged from little things, like ease of travel, to the broader sense of security that comes with having a U.S. passport.

I got my passport when I became a naturalized citizen, almost 20 years after that first visit to the Statue of Liberty. It was an emotional moment, not only because it signified the achievement of an intergenerational American dream, but because we were living under a presidency with immigrants in its crosshairs. At the time, President Trump was in his second year in office. His administration was committing terrible human rights violations against immigrants, like issuing the Muslim ban and refugee ban, and separating children from their parents at the border.

Mira Naseer, Harvard Law School student.

It felt strange to become an “official” American during a period of extreme hostility toward immigrants, Muslims, and women. I check all those boxes. Even filling out immigration paperwork filled me with anxiety given the political climate. During my naturalization interview, I was asked questions about what I do, my political leanings, and other personal details that made me very nervous — as if I might give the wrong answer and be denied.

Anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiment did not begin with Trump, but it was especially tangible and frightening when he issued the Muslim ban. Once that happened, it wasn’t just tweets and campaign rhetoric. I worried about my grandparents, who live in Pakistan but often come to visit. What would happen? Would they ever be able to visit us in the U.S. again?

The four years of Trump’s presidency very much changed my relationship with how I viewed the U.S. and my place within it. But they also solidified my aspirations to build a career advocating for immigrants’ rights. Today, I’m entering my third year at Harvard Law School after a summer internship with the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, where I worked on systemic immigration reform through litigation. Much of my work has centered on refugee rights, immigration, and immigrants’ rights. Naturally, I feel a personal connection to this cause. I know what it’s like to have your hopes hinge on a chance to build a future in a new country.

All forms of immigration are integral to the fabric of American life, and the diversity visa program is a critical part of that.

The beginning of a new administration this year gave me hope for change in the U.S. immigration system. But unless the administration takes action, thousands of diversity visa recipients will not be able to get to the U.S. unless they reapply and somehow win this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity yet again. Many people give up their homes and other possessions to afford the fees to apply, and now they will have to pay again. We can’t let these lottery winners be forgotten.

The diversity visa program is important because it opens doors to opportunities that people dream about. The program betters this country because it also allows many Americans to work and live side-by-side with people from all sorts of backgrounds — people with whom they might otherwise never cross paths. All forms of immigration are integral to the fabric of American life, and the diversity visa program is a critical part of that. We must honor it and provide relief for the thousands of people still waiting to realize their dreams like my family was able to so many years ago.