The Department of Justice is waging a long-running campaign to silence members and supporters of a controversial motorcycle club from expressing their affinity with the club by displaying its . This relentless attack should trouble anyone who cares about the freedoms of speech and association.

In a filing Friday, we’re telling a federal court how the First Amendment prohibits the government from banning symbols, no matter what they represent.

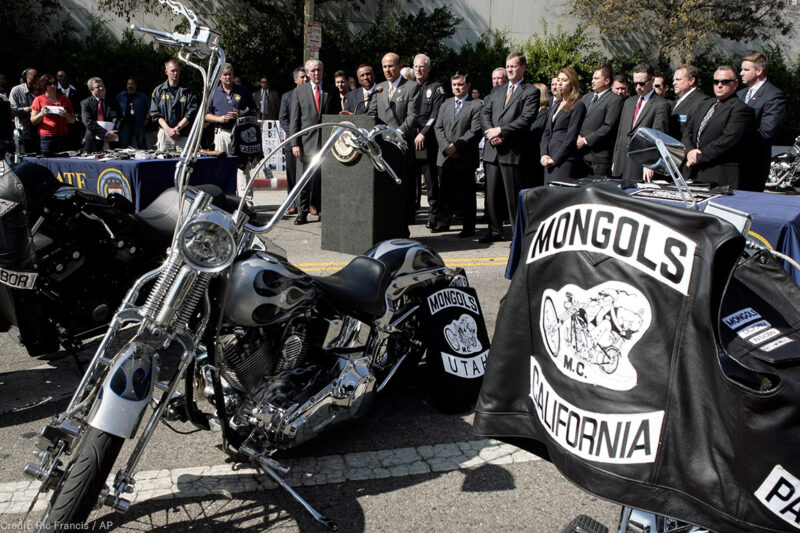

In 2008, the government filed RICO, or racketeering, charges against certain members of the Mongols Motorcycle Club. In the process, the Justice Department also sought forfeiture of the club's trademark in its logo, a distinctive design that combined words and images to signify membership in the group.

After members were indicted, the Justice Department obtained a pretrial order authorizing confiscation of items bearing the Mongols' logo. The U.S. attorney in Los Angeles that any officer who saw any club member “wearing his patch” could “literally take the jacket right off his back.” Officers did just that, confiscating jackets, belts, shirts, and other items displaying all or part of the logo from club members and supporters — even though they were not charged with any crime.

Representing a club member, the ACLU of San Diego & Imperial Counties halted this campaign of censorship in its tracks. The court ruled that the government had no right to seek forfeiture of the trademarks because they belonged to the club, not any individual member. The court’s also schooled the government in bedrock principles of trademark and First Amendment law, calling the government’s theory “creative to a fault.” Whatever crimes certain club members may have committed, the government misused its power when it violated the rights of others to express their identity as club members or supporters.

A trademark is a unique form of property: It does not exist apart from the business or entity it symbolizes, and it cannot be transferred independent of that business or entity. Because the government has no right to assume the identity of the Mongols Motorcycle Club, it cannot seize the club’s trademark.

Even if the government could take those rights, they confer no power to confiscate items bearing the trademark. A trademark does not confer an absolute right to prohibit all use of the mark. It only authorizes the holder to prevent purely commercial use of the trademark that creates confusion as to the origin of goods or services. That’s why the Campbell’s Soup Company couldn’t prevent Andy Warhol from painting images of Campbell’s Soup cans and Mattel can’t prohibit Danish-Norwegian dance-pop group Aqua from or stop an artist from . Likewise, the government could not legally prevent an individual from expressing support for the Mongols Motorcycle Club — or opposition to abuse of power — by wearing its logo.

Trademark issues aside, the First Amendment prohibits the government from censoring the right of people to express their membership in or support for an association. It also prohibits the government from targeting the content or viewpoint of speech associated with a particular group, regardless of what that group stands for.

The government certainly can’t prohibit people from wearing shirts or buttons supporting the Democratic Party, Black Lives Matter, or the National Rifle Association — and it can’t prohibit people from wearing the Mongols logo either.

Ignoring those principles, the government indicted the Mongols Motorcycle Club in 2013 for RICO violations, again seeking forfeiture of the club’s trademarks and threatening to confiscate items bearing the logo from members and supporters of the club. As we explain in our friend-of-the-court brief, the government’s attack on free expression remains no less illegal and unconstitutional now than when it began over 10 years ago. Neither the RICO forfeiture statute nor trademark law authorize the government’s unprecedented attack on speech, which violates foundational First Amendment principles.

Given the broad sweep of the RICO statute and corresponding abuse of forfeiture powers, the government’s novel theory threatens to set a dangerous precedent for silencing controversial or unpopular groups. History has shown that the first victim of censorship is never the last.