It’s 2022 and Two Books Are on Trial for ‘Obscenity’

Two books are currently on trial in Virginia for obscenity.

In 2022, that sentence should be shocking. Nearly 50 years ago, set the high constitutional bar that defines obscenity — a narrow, well-defined category of unprotected speech that excludes any work with serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. Since then, few if any books have been deemed obscene. And the standards for restraining a bookseller or library’s ability to distribute a book are even more stringent.

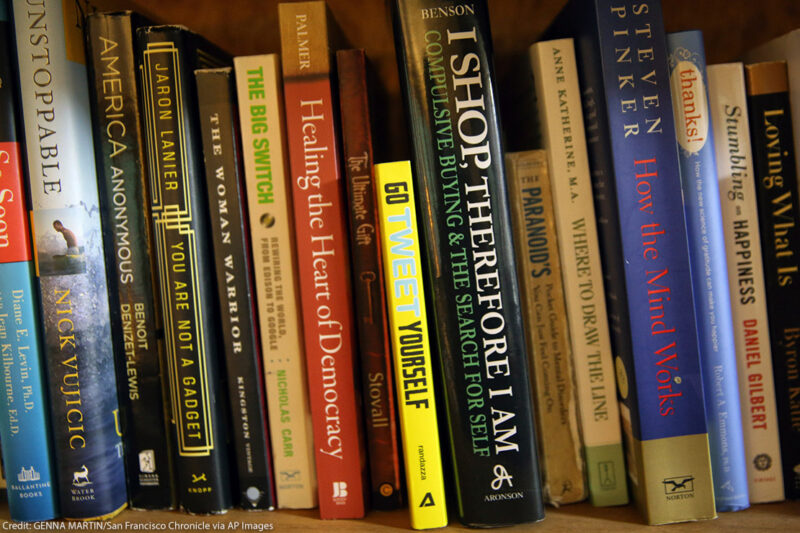

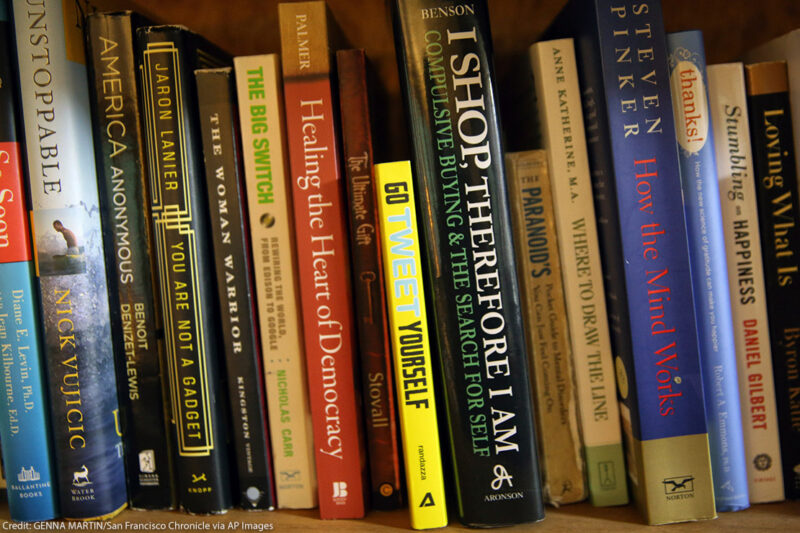

Yet, last month, a Virginia resident initiated obscenity proceedings against two acclaimed books: , by Maia Kobabe, an autobiographical graphic novel that depicts the author’s experience as a non-binary and asexual person; and , by Sarah J. Maas, a fantasy novel. The obscenity proceedings come amid a in efforts to restrict people’s access to books, and our ability to read, learn, and think for ourselves — but they could be the first to result in a statewide ban on publication or distribution.

Last week, several independent bookstores and a number of national organizations representing book distributors, authors, and libraries filed joint motions urging a Virginia court to dismiss these obscenity proceedings. We represent these distributors alongside the ACLU of Virginia and Michael Bamberger of Dentons, arguing that the case threatens the rights of both young and adult readers — and the First Amendment rights of our clients, as well as other booksellers, distributors, and publishers, to provide access to such materials.

The books at issue here are not obscene by any stretch of the imagination. And the that has enabled these proceedings is unconstitutional.

Under the statute, the court has the authority to temporarily block all sale and distribution of the books anywhere in Virginia upon a mere finding of “probable obscenity.” And, if the court ultimately determines that the books are indeed obscene, anyone who sells or even lends the books in Virginia could face criminal prosecution, regardless of whether they had prior knowledge of the obscenity proceedings. This would impact all independent bookstores and other distributors in the state of Virginia, even if they have no knowledge that a book has been so much as challenged. And it means a court can restrain the distribution of books that are not legally obscene — or, in other words, fully protected speech.

Furthermore, after entry of a temporary restraining order or a final adjudication of a book’s obscenity, the government can presume that anyone who sells, lends, or otherwise distributes the book in Virginia knows it is obscene. In essence, it creates a strict liability regime for selling or lending books that could impact incredibly broad swaths of people, from booksellers to parents to teachers and others.

Finally, because Virginia applies local rather than statewide community standards to determine obscenity, the law could unconstitutionally allow a ban against the circulation of a book that doesn’t even qualify as obscene in the relevant community.

For these reasons, our clients have asked the court to dismiss both proceedings. Any other result would be obscene.