In Georgia, deaf people ensnared in the criminal legal system are routinely denied sign language interpretation and other accommodations, dramatically disadvantaging them while in prison and at every stage of their criminal justice proceedings. The ACLU on Wednesday filed a motion seeking a class action lawsuit on behalf of currently and formerly imprisoned deaf people in Georgia. The motion highlights gross violations of their constitutional rights.

The criminal legal system is stacked against many of the most vulnerable Americans, including people with disabilities. At every stage — arrest, interrogation, trial, sentencing, prison, and parole — deaf people are more susceptible to going to prison more often, staying longer, suffering more, and returning to prison faster.

Deaf people with — including those who are LGBTQ and come from communities of color — fare even worse. Throughout the country, our system to provide sign language interpreters and other communication access, as required by federal law. Our case against the Georgia Department of Corrections, the Georgia Department of Community Supervision, and the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles — calls out these institutions for violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Rehabilitation Act, and the Constitution.

As a co-founder and volunteer director of (HEARD), I have been working with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people who are deaf and disabled for the last 10 years. Their experiences break my heart, haunt my dreams, and fuel my advocacy.

The problems they face are particularly acute in Georgia.

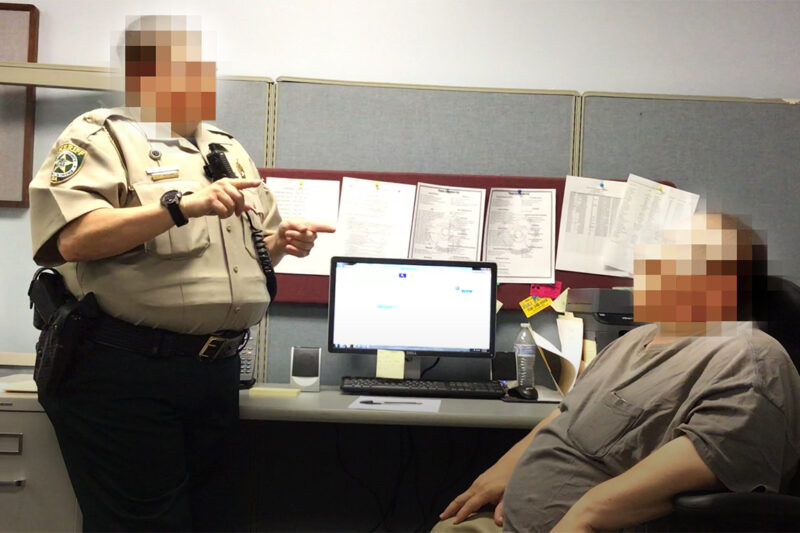

Take our plaintiff Ricardo Harris. Ricardo was a star student at one of the few colleges in the country that provides instruction in sign language. While on winter break visiting friends in Georgia in 2013, this bright, Black-Latino deaf man was arrested and accused of murder. He was tried and convicted. Over the course of two and half years of incarceration, he was not provided qualified interpreters during police interrogation or for communication with his own defense attorney. Without interpreters or telecommunication access, he could not participate in his own defense or even begin to tell his side of the story. He has been in prison, effectively barred from communication with attorneys, advocates, and loved ones, including a young child, since 2013.

Jerry Coen, another plaintiff in the case, was arrested for behavior related to addiction. He had tried to attend recovery programs, but could not find programs available in American Sign Language or a program that provided ASL interpreters. Like many people who use ASL as their only language, Jerry does not understand English.

The isolation of prison was devastating for Jerry. Without videophones, he could not communicate with his family. So, once a month, his parents would make the seven-hour round trip in order to spend a few hours with their son in prison. These visits were the only connection he had to the outside world for the 10 years he was incarcerated.

Jerry was regularly unfairly punished. The prison refused to use ASL interpreters to explain the rules or procedures he needed to follow, and he could not understand any of the written rules or information from the prison. Guards refused to use ASL interpreters when they thought he had broken rules. Disciplinary hearing officers refused to use ASL interpreters during hearings where they concluded that he had broken rules and set punishments. Jerry’s hands were handcuffed behind his back during these disciplinary hearings — sometimes so tightly that they left scars. He could not gesture or even try to write a few words in his own defense. Jerry spent a week in solitary confinement. His beloved father passed away just months before he was released in 2017.

Another plaintiff, Jonah Wooden, was supposed to attend substance abuse classes as a condition of probation. These classes had no interpreters. Jonah spent months sitting in class struggling to understand the content. When he asked for interpreters, he was told that he would have to pay for them himself, even though federal law requires the program provider to ensure effective communication. After months of dealing with the frustration and isolation of sitting through classes without interpreters — and even trying to pay for interpreters before he realized he couldn’t afford them — he stopped showing up. He was arrested for violating his probation, and is now serving two years in prison.

These are not isolated stories. There are hundreds more, in Georgia and throughout the country.

The injustices faced by deaf and disabled people in the criminal legal system are not widely understood, well-documented, or sufficiently challenged. But the stories of Ricardo, Jerry, Jonah, and hundreds of other deaf and disabled incarcerated people, coupled with scant research, paints a bleak picture: The criminal legal system — from start to finish — consistently violates deaf people’s constitutional, civil, and human rights.

We can and must do better. The ACLU and partners are seeking a class action lawsuit to ensure that the state of Georgia provides sign language interpreters and other needed auxiliary aids and services so that deaf people in its criminal legal system have the access that the law requires.

This case sheds light on the horrors of being deaf and imprisoned in the United States. We hope it also serves as encouragement for incarcerated people; a warning to prisons; and a call to action for advocates, attorneys, and people across our country to do right by deaf and disabled people and to hold our government accountable when it fails to do the same.