We Don’t Lose Our Privacy Rights When We Travel

Every year, millions of people cross the U.S. border through airports, land crossings, and other ports of entry. Each will pass through customs before entering the country. For some travelers, however, the process isn’t simple. A growing number of travelers are being detained and subjected to warrantless and suspicionless searches of their phones, laptops, and other electronic devices by border officers who may cite a host of reasons for doing so, or no reason at all. By searching travelers’ electronic devices, border officers can access a vast array of personal, sensitive information, including photos, texts, emails, internet browsing history, and location data. This happens to U.S. citizens, permanent residents, tourists, and business travelers.

In 2017, along with partners at the (EFF) and the , the ACLU brought a lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security challenging this fast-growing practice — and won. In 2019, a federal district court ruled that border agencies’ policies on electronic device searches violate the Fourth Amendment, and that border officers must have reasonable suspicion that a traveler’s device contains digital contraband before searching it. However, a three-judge panel of the First Circuit Court of Appeals reversed this decision in February 2021.

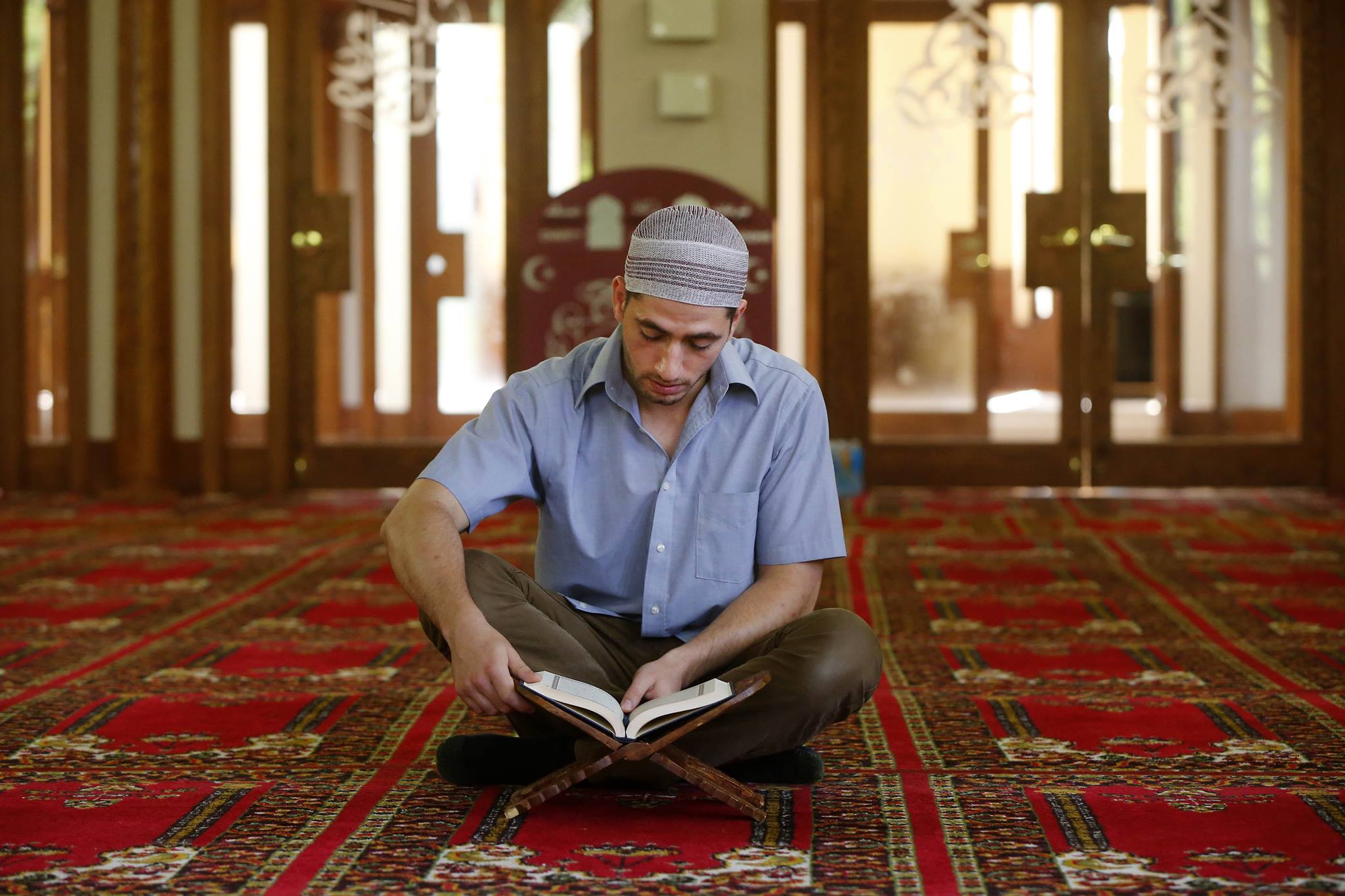

Today we are petitioning the Supreme Court to take up the case on behalf of our clients, including a military veteran, an artist, a NASA engineer, journalists, and others whose devices were searched at the border by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers. Several are Muslims and people of color. Their stories are stark examples of what happens in airports and other border crossings every day.

Zainab

As a Muslim woman who wears a hijab, Zainab has undergone prolonged, intrusive border searches repeatedly and has written about her experiences on her personal blog. One of those incidents occurred in 2017, while she was a graduate student at Harvard University. On her way back from a trip to Canada, CBP officers stopped her and demanded she unlock her phone and laptop, threatened to seize the devices if she did not comply, and questioned her about her religion, her travels, and even her blog. The invasive search drove Zainab to tears. She worried that the officers, who were men, would see photos on her phone showing her without her headscarf. When the officers finally gave her phone back, the Facebook app was open and displaying her friends list. It hadn’t been open when she turned over the phone.

Sidd

Sidd, an optical engineer from California, was on his way back from a solar-powered car race in Chile when CBP officers detained him and seized his phone at a Houston airport. When they demanded Sidd’s password, he tried to refuse, explaining that the phone belonged to his employer. The officers gave him a form stating “collection of this information is mandatory at the time that CBP or ICE seeks to copy information from the electronic device.” Without a meaningful choice, he finally surrendered his password.

When the officers returned Sidd’s phone, they told him they had used “algorithms” to search it — indicating they used forensic tools to capture and analyze the information contained in the device, including emails, texts, and other private information.

Akram

Akram, a native New Yorker and independent filmmaker, hesitated to hand border officers the password to his phone. They asked if he had something to hide. He ended up complying because he had no meaningful choice. Just days later, border officers again detained Akram and demanded his phone after a day trip to Canada. This time, he refused. Three officers responded with force, holding his arms and legs while choking him and inflicting severe pain as they took his phone from his pants pocket. Akram feared for his life.

Matt

In the spring of 2016, Matt, a software programmer from Colorado, traveled to Southeast Asia to visit friends and take part in ultimate frisbee tournaments. When he returned home, CBP officers in Denver detained him and confiscated his laptop, phone, and camera, and told him it could be as long as a year before he’d get them back.

Later, after submitting a Freedom of Information Act request with EFF, Matt learned that the government had extracted data from his camera and his phone’s SIM card, and attempted to use a forensic tool called MacQuisition to copy everything on his laptop. CBP disclosed to Matt that it did not find any “derogatory” information about him in his devices or otherwise.

Diane

Diane is a former Air Force captain and a university professor of homeland security and conflict studies. During her return from a trip to Norway in 2017, border officers in Miami pulled her aside, held her in a small room, and demanded she unlock her phone and laptop. As she watched the officers search her devices, she worried they would read her emails and texts, look at her photos, download her personal information and contacts, and share the data with other government agencies. She was released about two hours later, feeling humiliated and violated.

Isma'il

In July 2017, Isma’il, a freelance journalist, crossed the U.S.-Canada border on his way home from a short trip to Montreal with his classmates in a Middlebury College language program. Border officers demanded access to his phone and questioned him about his work as a journalist. He was released three and a half hours later.

The petition for certiorari, filed in partnership with EFF and the ACLU of Massachusetts, asks the Supreme Court to overturn the First Circuit’s decision and hold that the Fourth Amendment requires the government to obtain a warrant before searching electronic devices, or at least have reasonable suspicion that the device contains digital contraband. The Supreme Court must ensure that we don’t lose our privacy rights when we travel.