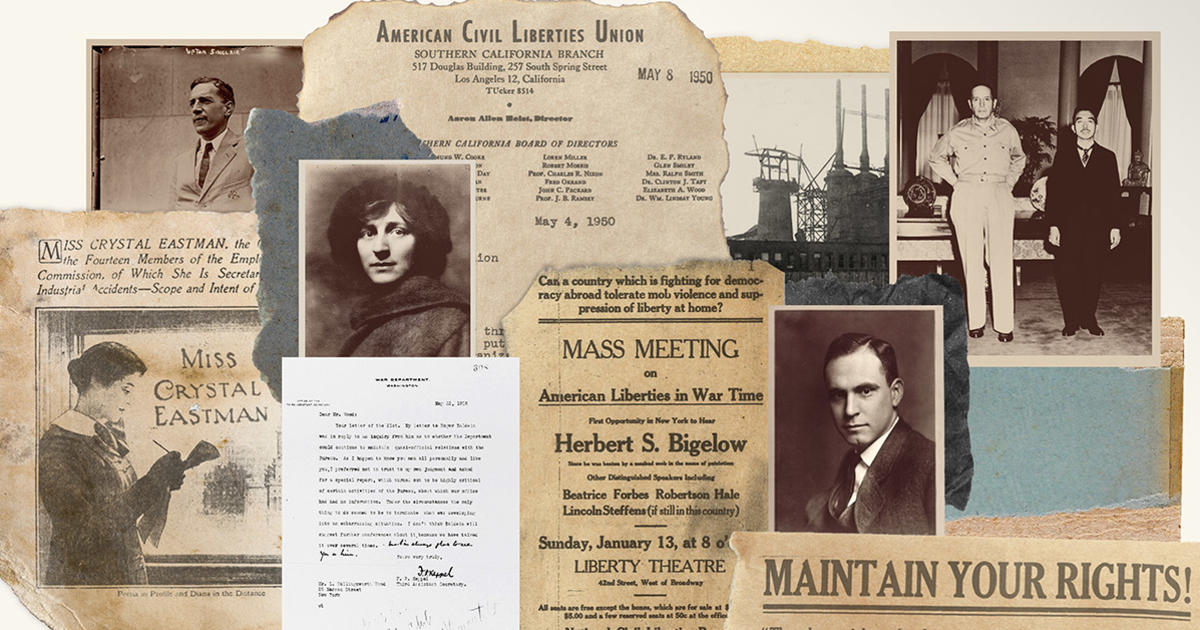

Rosika Schwimmer, Woman without a Country

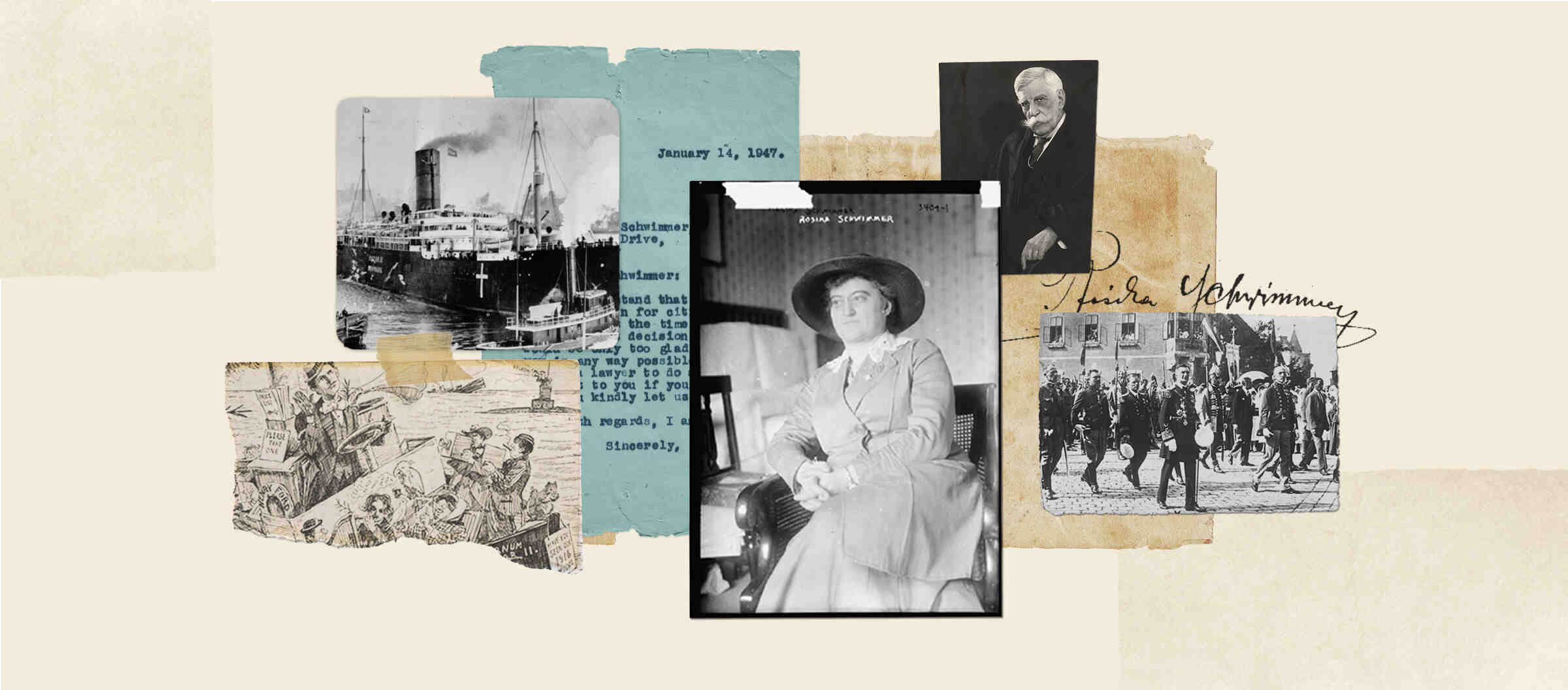

Rosika Schwimmer in 1914

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing

What could be more absurd than denying a middle-aged woman United States citizenship on the grounds that she would not promise to bear arms on behalf of the U.S. — something she never would have been called upon or even allowed to do in 1929?

“The whole thing is crazier than ‘Alice in Wonderland,’ but less funny,” mused Rosika Schwimmer, a Hungarian feminist, suffragist, internationalist, and pacifist, born Jewish, who found herself at the convergence of the fault lines of the 1910s and ‘20s: xenophobia, misogyny, anti-Semitism, jingoism, nationalism, and intolerance of dissident speech.

Rosika Schwimmer’s story is the stuff of opera. She experienced waves of acclaim and of vilification, of international renown and of exile — and was championed on more than one occasion by the ACLU, fighting the anti-civil liberties forces arrayed against her.

Fighting for Peace

As part of her determined effort to stop World War I, Rosika convinced American automaker Henry Ford to back and let her co-lead a , which sailed to Europe in December 1915 with the goal of convincing people of the neutral countries to do what governments would not: offer mediation to the belligerents.

But the Peace Ship, like the where Rosika had played a key role earlier that year, became an object of ridicule by the mostly male, sensationalist press. Rosika, dubbed an “enemy alien,” became the chief target of American reporters’ scorn as well as their relentless libel. In mainstream as well as super-patriot publications over the next decades, she was alternately (and sometimes simultaneously) falsely accused of being a German spy trying to undermine American preparedness for war, a Bolshevik spy, an adventuress who had duped Henry Ford into an extravagant and foolish venture for her own profit, and the precipitating cause of Ford’s anti-Semitism (on the theory that he became disenchanted with her and therefore her entire ethnicity).

Scandinavia-America Line passenger steamship Oscar II leaving New York as the "Peace Ship" on December 4, 1915.

Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

The ACLU supported Rosika’s 1928 libel action against reporter Fred Marvin, whose “Searchlight” column in the New York Commercial described her as both a German spy and a Bolshevik — the former because she had been a citizen of Hungary when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was allied with Germany, and the latter on the theory that after the war she had represented a Communist-led Hungarian government, which she had not. Rosika had been appointed Hungary’s ambassador to Switzerland in 1918 (she is said to have been the first woman ever to have served as a foreign ambassador), but she was recalled five months later when the Communist-led Bela Kun government came into power. That regime, regarding her as a bourgeois feminist, would not even allow Rosika to leave the country.

The ACLU’s first general counsel, Arthur Garfield Hays, who also maintained a private practice, represented her in the lawsuit. At trial, Hays conducted a classic cross-examination in which he got Marvin to admit that he had learned subsequent to publication that Rosika had not in fact represented the Communist government, but that he had not taken any steps to retract his false statement. On June 29, 1928, a jury awarded Rosika .

Hungarian leader Miklos Horthy, seen here leading soldiers in August 1931.

Wikipedia, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany

Rosika had fled Hungary in 1921, after the Bela Kun government was succeeded by the . Still not allowed a Hungarian passport, she escaped that government’s persecution by night on a Danube steamer. She always maintained that she did not adhere to any political party — certainly not any party of communists or fascists, whom she regarded as extreme and violent — or to any religion. Soon after, she emigrated from Vienna to the United States, hoping to resume her successful pre-war career as a celebrity lecturer and author.

Fighting for U.S. Citizenship

Once the requisite waiting period ended, Rosika applied for United States citizenship in Chicago. In 1926, after protracted proceedings, her application was rejected.

Rosika had the right to appeal that rejection in court but, exhausted by the constant attacks on her reputation and her poor health, she told friends that she would not have pursued an appeal “if organizations and individuals interested in civil rights in this country had not urged me to make my case a test, which none of them expected to fail.” As co-founder of the ACLU Roger Baldwin later said, in laying to rest a dispute over whether Rosika would reimburse the organization for part of the litigation expenses, “We got her into that suit and backed her in it.”

At the in Oct. 1927, Judge George Carpenter agreed that in all other respects Rosika was eligible for citizenship, questioning her only about her pacifism — particularly whether or not she was unwilling to bear arms on behalf of the United States. The judge , “The time will never come, I venture to say, when the women of the United States will have to bear arms.” Nonetheless, he invented a contrived hypothetical situation where a woman might be serving the military as a nurse, a nearby U.S. soldier would be threatened by an assailant aiming a gun at the soldier’s back, and a pistol would be available with which the nurse might shoot the assailant.

The court: “[W]ould you kill him?”

Schwimmer: “No, I would not.”

The court: “The application is denied.”

In addition to disdaining conscientious objectors, Judge Carpenter showed a characteristic 1920s lack of tolerance for the dissenting speech of pacifists which was viewed, even after the war, as unpatriotic and dangerous.

“Do you expect to spread this propaganda throughout this country with other women?” Judge Carpenter asked.

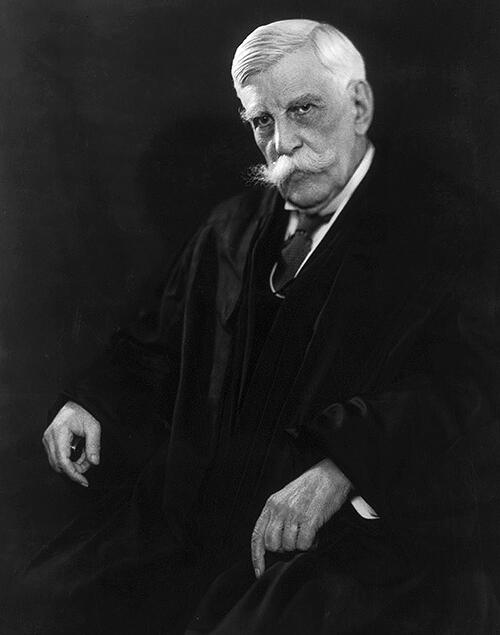

The American Civil Liberties Union's first counsel, Arthur Garfield Hays, shown in New York on August 20, 1943.

AP Photo/Carl Nesensohn

Arthur Garfield Hays reacted to the decision by writing to Rosika, “This is the most absurd proceeding I have ever heard of and I have no doubt of the result on appeal.”

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with Hays. On June 29, 1928, the very same day as the Marvin damages verdict in her libel suit, the to grant Rosika U.S. citizenship.

Rosika must have felt that she had finally emerged from a very dark rabbit hole. But the Department of Labor, determined to make an example of her, urged appeal to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court granted certiorari. Rosika’s case was ably presented by volunteer attorney , one of the first women ever to argue in the Supreme Court, who maintained that the naturalization statute in question was being misapplied.

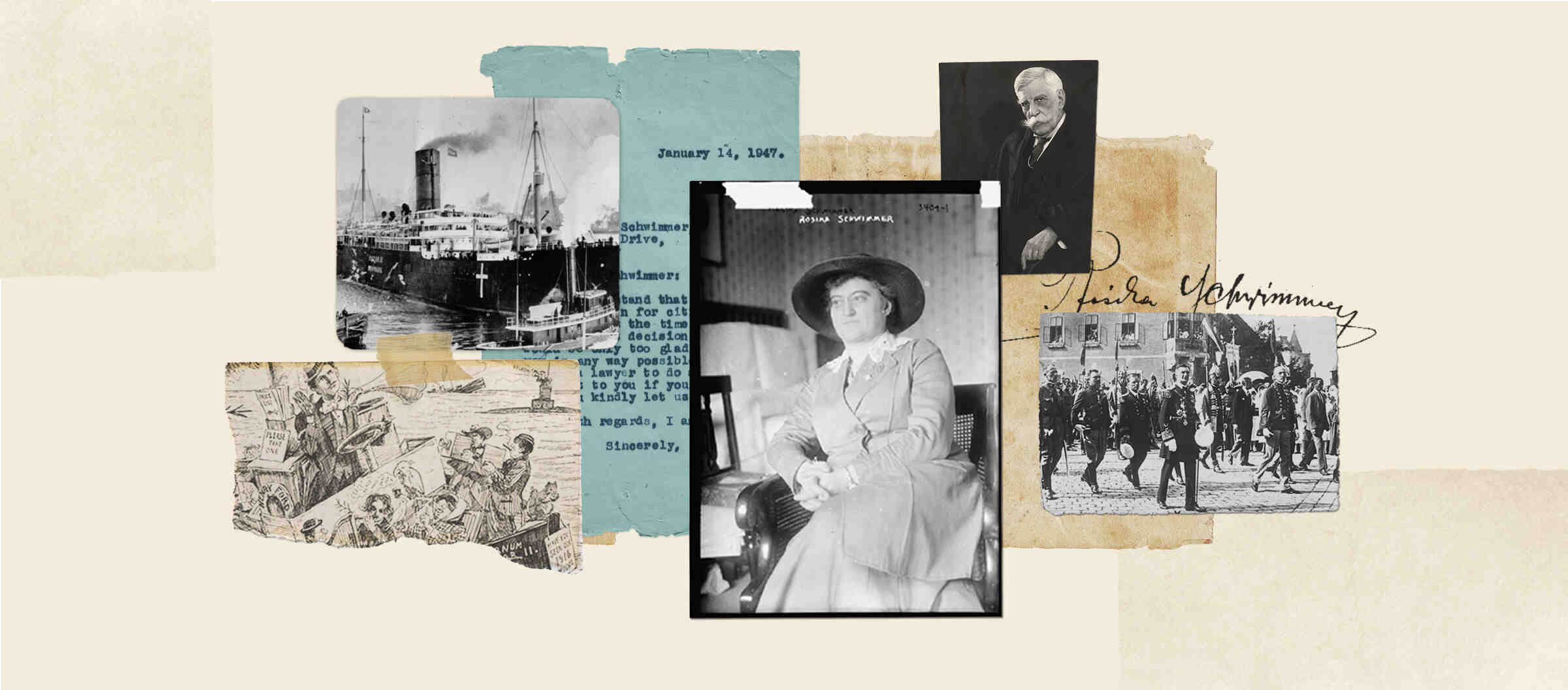

Supreme Court Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., circa 1930.

Harris & Ewing, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The ACLU was outraged when a six-justice reversed the appellate court’s decision, ruling against Rosika on the theory that because of her pacifism, she had not shown the “attachment to the principles of the Constitution” the governing statute required.

“The influence of conscientious objectors against the use of military force in defense of the principles of our Government is apt to be more detrimental than their mere refusal to bear arms,” read the decision. “The fact that, by reason of sex, age, or other cause, they may be unfit to serve does not lessen their purpose or power to influence others.”

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., joined by Justice Louis Brandeis, dissented in an inspirational First Amendment opinion: “[I]f there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other, it is the principle of free thought — not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate.” Rosika wrote to Holmes to thank him for his opinion, sparking a lifelong relationship.

Roger Baldwin was outraged by the Supreme Court’s decision and its rationale. Defense of conscientious objectors and of pacifist speech had been central to the work of the ACLU’s predecessor organization, the National Civil Liberties Bureau. Baldwin himself had been a conscientious objector. Within weeks, the ACLU issued a call to action entitled “” The 16-page pamphlet was headlined: “Congress can change the naturalization law. A bill has been introduced to overcome the Supreme Court decision. Support it. Read the facts of this case and help!”

The ACLU campaigned vigorously to amend the law, noting that the court’s decision would deny citizenship even to Quakers like current President Herbert Hoover. But the proposed bill stalled in Congress and Rosika Schwimmer was left a woman without a country.

Fighting Henry Ford

Due to the widespread smears emanating from the Peace Ship venture and the general effects of blacklisting, Rosika was no longer able to support herself through speaking and writing engagements, to her intense frustration. Her correspondence contains letters from agents confirming her suspicion that she was being boycotted. She believed that if she could clear her name, she could restore her livelihood.

In 1925, even before the Marvin libel action or the citizenship application, the ACLU had become involved in a campaign to help her set the record straight.

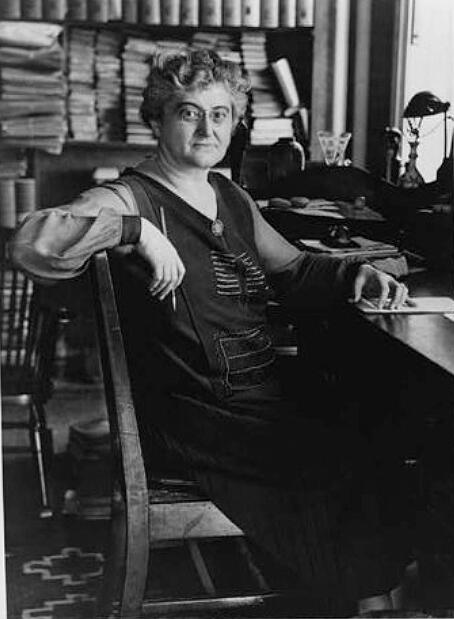

Rosika Schwimmer in 1927, after she was denied U.S. citizenship.

New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When the mercurial Henry Ford left the beleaguered Peace Ship soon after it docked in Norway, he privately expressed his confidence in Rosika’s continuing leadership of the venture but never met with her again, never backed her publicly, and never took action to correct any of the outrageous and untrue statements being made in the press. Rosika believed, with some justification, that the coterie surrounding the conflict-averse Ford might not have let him see her multiple letters pleading with him to state publicly that she had not received any salary for her work and that he did not believe her to be a German spy.

Even some of Rosika’s friends, like fellow suffragist , assumed that Ford’s silence was damning.

The ACLU released an open letter telling the true story of Henry Ford, Rosika Schwimmer, and the Peace Ship. Prominent signatories included ACLU founder Jane Addams and Clarence Darrow. But Rosika’s reputation remained tattered.

"Tisza Tales" book jacket, 1928-1929

The New York Public Library. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-d22c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Fighting for Reputation

Rosika spent considerable time from the 1920s to 1940s doggedly pursuing and writing reams of letters to individuals and publications in a frantic effort to correct the record. She had a clipping service to help her keep track of the false statements in publications around the country. But the damage was irreparable. Rosika relied on her sister and Lola Maverick Lloyd, a loyal friend from the Peace Ship, for financial support. But lack of funds forced her to abandon an expensive treatment for her diabetes as well as pursuit of further libel actions — including an appeal in her . The only thing Rosika managed to get published during this time was a volume of charming Hungarian folk stories called Tisza Tales.

Rosika’s friends around the world made to resurrect her good name by nominating her for an honorary World Peace Prize, which she was awarded in 1937.

During the 1930s and 40s, Rosika worked feverishly to help refugees, many but not all Jewish, to escape Hungary and other parts of fascistic Europe and build new lives. Albert Einstein called her his “saving angel.” She had no funds to share and as a non-citizen she could not sign sponsorship affidavits. But she used her capacity for voluminous correspondence to enlist friends, acquaintances, and sometimes even complete strangers to help some of the hundreds of desperate people who appealed to her. She wrote to stage star Ethel Barrymore, for example, to beg help for a refugee who was a playwright.

Rosika Schwimmer, Henry Ford, and Louis Lochner on the Peace Ship in 1915.

Underwood & Underwood, photographers, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Many blamed Rosika for causing her own downfall. Critics condemned her management style on the Peace Ship as tyrannical and devious. She was accused of exaggerating evidence that the neutral countries were willing to engage in a mediation effort, and of trying to manipulate the press and the process. Most accept those negative views of her conduct and character.

, her co-leader on the Peace Ship, more sympathetically portrayed Rosika’s tragic flaw as one of style: her old-world European manners and her determination to fight for peace in the way she thought most likely to succeed grated against American democratic sensibilities.

At the other extreme, adoring fans continued to regard her as an inspirational “Joan of Arc” figure and blamed Henry Ford for the venture’s failure: He was the one who had precipitously announced in November that their delegation would end the war and bring the boys home in time for Christmas, leading to a hasty sailing on Dec. 4 which did not allow time for adequate preparation or planning. And he was the one who abandoned the expedition and Rosika. Whatever the truth, being an assertive Hungarian and Jewish-born woman internationalist in that era amounted to so many strikes against her that Rosika undoubtedly would have been a magnet for criticism and ridicule even if her strategies and tact had been impeccable.

Observers reported that the Peace Ship experience transformed Rosika Schwimmer from a woman who was magnetic, fun-loving, smoking, laughing, and confident to a tragic figure: broken, disillusioned, embittered, and ill — she had a heart condition, and the diabetes she developed was linked to stress. But she continued to attract staunch friends and allies, including at the ACLU.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Reversals

The Supreme Court eventually reversed the Schwimmer decision in 1946, in . At the suggestion of Carrie Chapman Catt, Roger Baldwin wrote to Rosika in January of 1947, offering to help her reapply for citizenship and saying the ACLU would be “only too glad to assist you in any way possible.”

But Rosika responded that she had been exhausted by the earlier citizenship battle and was not willing to try again unless the process would be fairly automatic. (She mistakenly believed and hoped that the Seventh Circuit decision ordering that she be granted citizenship would simply be reinstated.) ACLU staff counsel explored the possibility of a private bill in Congress, an idea eventually abandoned as impractical, or a renewed application. But no one could promise Rosika that a renewed process would be uneventful, and she never again tried to seek citizenship.

Rosika Schwimmer shown on April 12, 1946 at age 70.

AP Photo

In 1948, 33 members of parliament from countries where Rosika Schwimmer was known due to her World War I peace efforts — including Britain, France, Italy, Hungary, and Sweden — nominated Rosika, the woman without a country, for the Nobel Peace Prize. She died on August 3, 1948, before the committee completed its deliberations. Unusually, no Peace Prize was awarded that year.

It is strangely fitting that Rosika Schwimmer’s life ended without a resounding vindication and even without resolution. Her own version of the story of her life ended with her death. An unfinished manuscript of her autobiography rests in the New York Public Library , along with more than 500 boxes of her papers. Brief accounts in later news stories, encyclopedias, articles, and books where Rosika is a minor character sometimes offer positive accounts of her work for women’s suffrage and peace, and sometimes negative accounts of the villain of the Peace Ship venture. But this largely forgotten woman without a country also remains a woman without a biography.

Susan N. Herman was elected President of the American Civil Liberties Union in October 2008 after having served on the ACLU Board of Directors and as General Counsel. As Ruth Bader Ginsburg Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School, she teaches courses in Constitutional Law, Criminal Procedure, and seminars on COVID-19 and the Constitution, Law and Literature, and Terrorism and Civil Liberties. Her most recent book, Taking Liberties: The War on Terror and the Erosion of American Democracy, won the Roy C. Palmer Civil Liberties Prize.